Writing Through Trauma, Past and Present: On the Legacies of Catholic Ireland

Elaine Feeney Considers the Emotional Journey to Her Novel, As You Were

When I was a child, I had an accident that caused trauma to my mouth. This resulted in years of infections, pain and surgery, so by adulthood, exhausted from recurrent sickness and my body’s persistent battle against me, I developed a belief that the mouth was separate to the body. I would deny pain until the last minute. I would freeze.

As it turns out, the mouth is important, as important as say, the liver, skin, even the heart. In 2007, at 18 weeks pregnant, I collapsed and was taken to hospital. As usual, I had had many warnings. I dropped a glass of orange juice I was taking to my young son and shortly after, a blue dinner plate dropped from my hands and smashed. After scans, where I was terrified my fattening belly would get stuck in the plastic cylinder, I was diagnosed with a brain clot—most likely connected to the childhood accident. My cubicle now buzzed with doctors fussing with cannulas, bloods, 15-minute neurological observations; Who am I? Where am I? Who is the President? Draw a clock.

And prayers—if I wanted them.

I didn’t.

Hospitals are filled with artificial light, even on the brightest day, long fluorescent tubes hum and people fill your space. You have no control of your environment. Food arrives on blue trays. Sometimes there’s laughing, sometimes crying. Someone is always talking. Someone is sitting on a leather chair contemplating their death. There is always tea and thank you’s. I thanked them for a daily blood thinning injection. I thanked them for bringing me to the toilet, and waiting. I repeated, I’m sorry. Soon, I grew familiar with late-night activity on the corridor. People came onto this maternity ward in crisis, sometimes flustered and often apologizing; for what they had done; what they had not done; and often, tragically; apologizing for what had been done to them. For the morning after pill. For an STD screening. For a rape kit.

“You’ll feel different when you are a mother,” one doctor said. “I am a mother,” I said.

Between repeats of The Godfather and antique furniture shows, I tentatively questioned doctors about my diagnosis. Not wanting to be judged for asking directly—abortion was illegal in Ireland—I hinted about options, but left frustrated at a lack of consistent information, I confided in care-assistants, patients and Google. Eventually I asked; If I have a termination would I be less likely to stroke? What do you mean when you say balance? What are the actual odds? Would my treatment be different if I wasn’t pregnant? I explained my terror of being unable to look after my older child if I ended up with paralysis.

“You’ll feel different when you are a mother,” one doctor said.

“I am a mother,” I said.

Ireland has a bleak historical record in its treatment of women and children; Mother and Baby “Homes”, Magdalene Laundries and a long history of Institutions. The patriarchy found an ally in Independent Ireland. Catholic social teaching provided the ethos for a conservative, protectionist state. Health, education, social care and other institutions would be run primarily by the Catholic church, supported by the state in a quasi-theocracy. Recent liberalization has not changed this order of things completely. During the infancy of the new Free State, in 1927, an act was passed exempting women from jury duty, and the sale and importation of contraceptives was banned in 1935. Before they banned the sale, they banned all knowledge of them, censorship laws being a crux of the Free State policies. In that same year, women employed as public servants could not work after marriage.

Culturally, conservative attitudes around sex and the body prevailed for decades. In 1992, news broke of a girl who was raped and became pregnant in Ireland. Soon it became known as the X Case, a seismic and emotive moment. I was 13, living in rural Ireland, realizing that my body was a public thing too; that I was different to my brothers; that we were valued differently both in the microcosms of my own family unit and now, in the macrocosm of the state. At the time, I didn’t discuss this with anyone. We didn’t talk about it at school or at home. It would take time for language to come.

My maternal grandmother was a small, anxious woman from a town called Tuam. She gave birth to 11 children. After her seventh child she courageously visited a priest to explain the danger of another pregnancy due to gestational diabetes. He replied that she should do her duty. Later in life she was in constant pain with no confirmed diagnosis or comprehensible description to explain it, selectively silenced.

In 2012, Catherine Corless, writing for a local history journal, drew attention to the conditions in the Tuam Mother and Baby Institution that had operated in the town my grandmother grew up in. The story garnered significant media attention over high mortality rates in the institution, where pregnant women and girls, mostly unmarried, were sent to give birth, and the particularly cruel burial practices—babies and children who died there were evidently buried in a sewerage facility. In the same year, Savita Halappanavar, died in a Galway hospital from septic shock following an incomplete miscarriage. Her request for an abortion was denied. Savita’s death was the catalyst to reviving the campaign to Repeal the Eighth amendment, becoming a civil rights’ issue for the generation that had brought about same-sex marriage.

While nationally, individuals continued sharing stories of forced birth, incarceration, illegal adoptions, symphysiotomies, rape, the penalty of poverty, institutional and child abuse and denial of choice or support from a state that historically devalued children born outside of marriage. It was overwhelming. As a writer, I needed to decant both the personal and political.

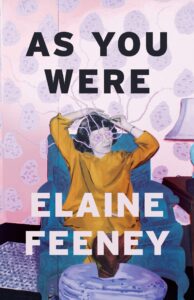

In my novel, As You Were, the protagonist Sinéad, after she is diagnosed with a terminal illness, freezes. The fight or flight response is a well-recognized phenomenon. The freeze response to an experience, or multiple experiences, is less commonly recognized. After months, Sinéad ends up on a hospital ward in Galway with a motley crew of strangers who reveal secrets of their own. Margaret Rose and Jane, two characters on the hospital ward who are, like many of their generation, impacted by Ireland’s conservative regime. Jane recounts the story of a friend who was incarcerated in the Tuam “Home” and subsequently sent to a Magdalene Laundry.

Communication on the claustrophobic setting of the novel’s hospital ward among the characters in As You Were arrived during the writing process in a frenetic fusion of dialogue, lists, text messages, intrusive thoughts and experimental prose. The prose style is chaotic and circular, reflecting the generational repetition of trauma. Language was complicated by memory for the characters, pain had pulverized speech. By the end of writing the novel, I remained haunted with frenetic echoes. I still can’t escape them, individuals who defied the system, succumbed to it, were harangued and destroyed by it, and those who helped, or hindered.

I now recognize that the mouth is part of the body.

In 2018, Ireland voted to repeal the Eighth Amendment in a national referendum. Today, the Tuam Mother and Baby “Home” Survivors still await redress and some, the exhumation of loved ones.

_______________________________________

As You Were by Elaine Feeney is available now from Biblioasis Books.

Elaine Feeney

Elaine Feeney is an award-winning writer from Galway and teaches at The National University of Ireland, Galway. She has published three collections of poetry, including The Radio was Gospel and Rise and the award-winning drama, WRoNGHEADED with The Liz Roche Company. As You Were, her debut novel, was published in 2020 by Vintage in the UK and in 2021 by Biblioasis in North America. It was shortlisted for Novel of the Year at the Irish Book Awards and was included in The Guardian’s top debut novels for 2020. It appeared widely in best books of 2020 including in The Telegraph, The Irish Independent, The Evening Standard, The Guardian, The Observer and The Irish Times.