Writing the Memoir My Father Never Could

Margot Singer: “That book... was not the book my father wanted. But it was the only one that I could write. It spoke the only truth I knew.”

Toward the end of his life, my father decided he wanted to write his memoirs. The only problem, in his view, was that he couldn’t type. He tried dictating to my mother, then a Dictaphone, and then the voice-to-text function on his Mac. Nothing worked. I offered to interview him, record our conversation on my iPhone, and send him a transcript, but after just one session, he gave up. What was the trouble? No one knew. Maybe he felt self-conscious. Maybe he needed more time to think. Maybe the words simply wouldn’t flow. English was his fourth language, after all, and writing was not his strength.

In our family, my mother was the lover of books. She was the one who brought me to the library when I was little, introduced me to all her favorite authors, and read to me out loud (All of a Kind Family, the Chronicles of Narnia) before I went to sleep. Only occasionally could my father be cajoled into telling me a bedtime story. Preferring invention to reading, he made up zany tales about a mischievous brother-sister duo improbably named Limpitaudus and Limpitaudusina (inspired, no doubt, by his childhood exposure to those gruesome German tales, Max und Moritz and Struwwelpeter). But despite their imaginative spark, my father’s stories all too quickly petered out.

I didn’t want to write a tribute to his career. I wanted to know where he came from, who he was—and who I was as a result.

My father almost never spoke about his own life. I pieced some of the details together from photographs and from the stories my grandmother would tell on our brief yearly visits. With her characteristic high, light laugh, she offered little glimpses into what my dad was like when he was growing up: how he made his younger brother crawl around like a horse while my father rode on his back; how he teased the dogs and kept pet tortoises on the balcony of their flat; how he begged to live on a kibbutz; and how once, when he first got his driver’s license, he rear-ended the family doctor’s car while showing my grandmother the view.

You would not have known, from listening to those stories, that my grandparents ran away from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia in 1940, when my dad was nine years old, landing on the alien turf of Mandatory Palestine, bereft. You would not have known that my grandmother’s parents and her sister and nearly every other relative on both sides of the family were murdered at Auschwitz. My grandmother laughed when she told me how my father hid in the bathroom when he got a bad report card; she didn’t mention the fact that he’d been thrown into school not knowing how to read or speak a word of Hebrew. She smiled when she told me about the letter my father sent from Boston saying he was getting married to a girl they’d never met, and she smiled when she told me about the telegram she got bearing the news that I’d been born, but she never hinted at her sadness at being so far away. I suppose she told me stories meant for children. How she really felt, I never knew.

My father certainly didn’t talk about his feelings. He was the kind of man who, as Flannery O’Connor once put it, was “conscious of problems, not people, of questions and issues, not of the texture of existence, of case histories and of everything that has a sociological smack, instead of with all those concrete details of life that make actual the mystery of our position on earth.” A consultant, entrepreneur, and textile engineer, my father was a problem-solver. He took the measure of his life—and mine—with the yardstick of achievement: successful ventures, prestigious institutions, financial rewards. He was not interested in probing “the mystery of our position on earth.”

Eventually, my father gave up on writing his memoirs and instead produced an outline: a list of his professional achievements scrawled over several pages of a legal pad. His curriculum vitae, if you will. He presented it to me, then led me into the dining room where he had laid out across the table an array of artifacts: trade journal articles, consulting reports, brochures, fabric swatches, expired passports, a couple of loose photographs. He made a grand sweeping gesture with his arms, and said, “Now you can write a book about my life.”

But what could I write? Stories come to life only through concrete, sensory details, but my father only spoke in vague and abstract terms. As Flannery O’Connor put it, the writer “appeals through the senses, and you cannot appeal to the senses with abstractions.” The memorabilia arrayed across the dining room table were a start, but they weren’t nearly enough. I needed the concrete, sensory details that went with the objects: names, places, images, textures, sounds, smells. Moreover, I didn’t want to write a tribute to his career. I wanted to know where he came from, who he was—and who I was as a result.

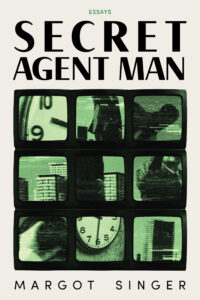

Creative nonfiction offers a flexible, imaginative space in which to explore these kinds of questions. I wrote an essay, “Lila’s Story,” that braided memories of the stories my grandmother told me together with the true story of my relationship with a married man and an invented story about an affair I imagined my grandmother might have had (but did not). I wrote another essay, “Secret Agent Man,” that set descriptions of the 1960s TV spy series alongside excerpts of conversations I’d had with father and memories of how I’d spied on him—and kept my own secrets—while I was growing up. Braided and segmented essays presented a way of allowing details and memories to rub against each other, setting them in motion, creating layers, and casting my understanding of my father—and myself—in a fresh light. The writing came to life in a way my father’s outline never would.

“Secret Agent Man” poked gentle fun at my father’s elusive behavior (not to mention his toupee, a taboo topic in our family) and made my friends and husband laugh. Of course, I had no intention of showing it to my dad. I didn’t worry when the essay was picked up for publication by a tiny literary journal that was neither sold in retail stores nor available online. But I was mortified when, somehow, my dad found out. I was terrified that he would be offended, that our relationship would be ruined for good. I tried telling him that the essay was “classified information,” but he told me he’d sent off an $8 check and would be getting a copy of the journal in the mail. Luckily for me, my father was a generous man. A few weeks later, he called to say that I wrote very well, even if I had gotten some of my facts wrong. I was too ashamed to ask which facts. We didn’t talk about the essay again for nearly twenty years.

The only memories I could access were my own. I had more to say about what I didn’t know than about what I did.

Even in the delirium-addled days before his death, my father continued to urge me to “write the book” about his life. Every time, the conversation made me cringe. I understood that he wanted to be honored and remembered, for his life to have had meaning, to leave a lasting trace upon this earth. I wanted to honor his wishes. And yet I could not do it. I didn’t know enough. I didn’t have the details.

In creative writing as in life, concrete objects function as containers of memory and emotion. Memorabilia, souvenirs, and keepsakes take us back in time. (Perhaps that is the reason it’s so hard to throw stuff out—and so liberating once you do.) Like artifacts uncovered in an archaeological dig, the objects that filled my parents’ house offered clues that I could only piece together through my imagination, never truly know. The only memories I could access were my own. I had more to say about what I didn’t know than about what I did.

Just a few days after my father’s death, I came across an email calling for submissions to a creative nonfiction book contest. I was still at my parents’ house and it was late at night. My mother had gone to bed, but I couldn’t sleep. I was sitting on the couch in the den in the spot where my father always sat when he watched TV. The paintings he’d collected hung on the walls. A pair of his reading glasses and a tin of his favorite candy lay on the table at my side. Our much-younger faces smiled out from framed photographs on the mantle. I opened my laptop and pulled up the personal essays that had been accumulating all those years. I cannot say I felt I had permission, but I knew that it was time. I copied and pasted them into one document, uploaded it to the portal, and clicked “submit.”

That book, Secret Agent Man, was not the book my father wanted. But it was the only one that I could write. It spoke the only truth I knew.

__________________________________

Secret Agent Man by Margot Singer is available from Barrow Street Press.

Margot Singer

Margot Singer's essay collection, Secret Agent Man, was released by Barrow Street Press in June. She is the prizewinning author of a novel, Underground Fugue, and a linked short story collection, The Pale of Settlement. She is also the co-editor, with Nicole Walker, of Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction. Her awards include the Flannery O’Connor Award, the Edward Lewis Wallant Award, the Reform Judaism Prize, the Glasgow Prize, the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, as well as grants from the NEA and the Ohio Arts Council. She is a professor of creative writing at Denison University in Granville, Ohio.