Writing the Anxiety of Parenthood on the Precipice of Apocalypse

Emma Szewczak Considers Questions of Procreation and Responsibility in Post-Apocalypse Narratives

The first post-apocalyptic novel may have been written by a woman—and Mary Shelley, no less— but tropes primarily followed by male writers have come to define the genre: a societal descent into violence and cannibalism; an individualist fight for survival; the Hobbesian pursuit of self-interest at all costs. In other post-apocalyptic novels, though, especially those written by women and non-cisgender people, the prospect of the end of the world is not only used to criticize human character, but to grapple with some of the more uncomfortable truths of the present. One such focus is reproductive rights, a contentious battleground even in the absence of post-apocalyptic circumstances.

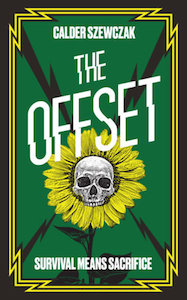

I co-wrote my own post-apocalyptic novel, The Offset, just after I gave birth to my first child. I spent long nights pouring out my anxieties over bringing new life into the world amidst a climate emergency to my friend, Natasha—before long, we had begun to tease those anxieties into a plot. In the world we created, one very close to the current climate reality of our own planet, the atmosphere has reached a tipping point and global carbon saturation is at critical mass. In a desperate attempt to reduce carbon, a population control strategy, the Offset, has been put in place. The Offset requires every new child to replace one of their parents. On their 18th birthday, they decide which one will die. The chosen parent then goes to their execution, and willingly.

This sacrifice is a culturally accepted phenomenon: it is a rational matter of balance, a “one in, one out” mentality. Its cultural impact has been to make anti-natalists of the world. Procreation is frowned upon. Those who do decide to have children are considered naive, stupid, selfish, or privileged (because it is a privilege to cling to the anachronistic belief that the planet has a future). Those living at the coal face of the grim reality of climate change have long since dispensed with hopeful notions of planetary reprieve. Only the rich, in their ivory towers, can convince themselves otherwise.

In Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985, the assumption is that a society wants (and needs) children. It is wholly according to this “function” of women that they are reduced, and it is the chief source of their oppression. Similarly, in her 1992 novel The Children of Men, P. D. James proposed that a world without children would fall apart. In the book, widespread childlessness means political isolationism, existential disillusionment, and outright nihilism. James depicts a people left with no sense of a future, trapped eternally in a violent present. Society cannot move on, better itself, or plan for liberation because of this very lack of a future. The book prophesizes: “[m]an is diminished if he lives without knowledge of his past; without hope of a future he becomes a beast.”

Fast-forward a few decades, and this view of childlessness is much less convincing. It is no secret that having fewer children is by far and above the most impactful way to cut your carbon footprint. Switch to a plant-based diet? That will save you 0.82 tons of CO2 per year. Cut out a single transatlantic flight: 1.6 tons. Eschew your car in favor of public transport: 2.4 tons. But have one fewer child: 7.8 tons. As Gavin Jacobson observed when discussing Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 film adaptation of the book, “In relation to Children of Men, the irony of the climate crisis is that we are now forced to ask: is it even OK to have children? Unlike Cuarón’s film, in which the end of children is the source of humanity’s collapse, some are now wondering if the end of children is the key to our salvation.”

It is ironic that women are framed as more culpable for this particular aspect of climate change, given the fact that the climate crisis disproportionately affects women.

The carbon impact of having children, and the responsibility of this, falls heavy on the shoulders of women—women whose bodily and reproductive freedoms depend on the potential to have children if they so desire (or otherwise). This anxiety and guilt involved in childbearing is a main thread in many new post-apocalyptic books written by women, reflecting shifting cultural attitudes towards reproduction. In Kate Sawyer’s The Stranding, the protagonist Ruth finds herself pregnant after the apocalypse, which she remarkably survived by climbing into the mouth of a whale. So, too, does the unnamed protagonist in Bethany Clift’s Last One at the Party, the seeming sole survivor of a deadly virus.

In both cases, it is difficult not to read these women’s extreme childbirths—undertaken in the woods, or on the beach, outside of hospitals and free from medical intervention, and featuring, in the case of Last One at the Party, an unmedicated and self-administered episiotomy—as an atonement of sorts. Or, perhaps, a punishment: one for the crime of having children in the context of a climate emergency. These books seem less interested in diagnosing what it is, precisely, that ended the world, but rather with how their female protagonists encounter its harsh realities.

In Susannah Wise’s This Fragile Earth, the subject is seen through the lens of technological advancement, as the book posits how new technologies can facilitate the illusion that climate emergencies can be avoided. Signy, the protagonist, already has a six-year-old son by the time technological collapse brings society crumbling down. This comes in the wake of planet-wide environmental devastation caused by deforestation, nuclear waste, and agricultural chemicals. Human efforts to correct this damage go awry: a species of beetle introduced to consume and counterbalance crop chemicals quickly becomes a blight, thoroughly decimating local bee populations. Various bots, algorithms and nanotechnologies are employed in the effort to combat these symptoms of the end times, but when they fail, so does all hope of a stable environment fit for human habitation.

In many ways, Signy’s context closely resembles our own: hers is a world which has been destroyed by human behavior, then patched back together using contemporary technologies which do not, in the end, suffice. Until that point of collapse, however, people largely shield themselves from the encroaching climate reality. Much like today, some people, particularly the wealthy, can place their faith in new technologies or take comfort in the thought that humans can, if they need, abandon the planet entirely. Signy is unable to harbor such illusions once the technologies of her world finally and completely fail; at that point, she must come to terms with what it means to have created new life in the first place.

It is ironic that women are framed as more culpable for this particular aspect of climate change, given the fact that the climate crisis disproportionately affects women. Seventy percent of those living in poverty are women, rendering them most vulnerable to the vast social, economic and cultural impacts of a precarious climate. As the Climate Change Unit of the UN puts it:

During extreme weather such as droughts and floods, women tend to work more to secure household livelihoods. This will leave less time for women to access training and education, develop skills or earn income […] When coupled with inaccessibility to resources and decision-making processes, limited mobility places women where they are disproportionately affected by climate change.

It is women, then, who face the brunt of a changing climate, reliant on numerous external systems to protect them from the full force of its wrath as they are.

My children deserve more than my life—they deserve their own.

A different narrative is emerging, though: new, post-apocalyptic books rally against a sense of reliance on other people and systems and the various vulnerabilities that accompany that reliance. In The High House, Jessie Greengrass depicts a self-sufficient refuge where the protagonist, Caroline, rides out the storm. In some ways her “high house” (placed, as it is, on a hill above the flooded waters of East Anglia) is presented as idyllic. There is an orchard, a vegetable garden, and a mill—spaces where Caroline is in complete control of her small, protected world, resources and the safety of her family. Her stepmother, who created the space as a safeguard against the coming apocalypse at a time when others ignored it, enabled Caroline to drop her dependence on multiform systems of production and protection, rendering her—ironically, at the end of the world—a free agent.

Whereas The High House depicts nostalgic scenes of traditional back-to-roots style homesteading, Bethany Clift’s Last One at the Party liberates its protagonist through… parties. In a newly empty world, in which she is seemingly the sole survivor, the protagonist basks in her solitude, making the most of London’s empty hotels, shops, museums, and sights. She sings on the stage of the Royal Albert Hall; she runs amok in the food court of Harrods; in the end, when she has her child, she does so on her own terms, too.

In my own writing, I don’t let myself off the hook for having children quite so easily. The real moral questions at the heart of The Offset are less to do with how to answer to the rest of the world for having children, and more to do with how to answer to your children, themselves, for having them. How do I justify bringing them into a world that might not have a future; how do I justify the fact that they are condemned to mop up the messes caused by my own generation and those before it, or risk facing potential extinction?

Many of these other books written by women are concerned with the allegations leveled at us all for exercising our reproductive rights and how these allegations, in whichever form, always serve to oppress us. I am most interested, instead, in examining the power imbalance between parents and children in this situation: one that is always present in the act of making a person exist who never consented to that. The Offset practice is an abnegation of that responsibility, one that comes up every time we all watch Greta Thunberg stand up and beg us for a future. My children deserve more than my life—they deserve their own. My children deserve to live in a world where post-apocalyptic fiction is only that: fiction.

_________________________________________________________

The Offset, by Calder Szewczak, is available now via Angry Robot.

Emma Szewczak

Emma Szewczak researches contemporary representations of the Holocaust and has published work with T&T Clark and the Paulist Press. She is half of the writing duo Calder Szewczak, with Natasha C. Calder, who she met while studying at Cambridge.