Writing in Tandem: Inside the Process of Cross-Racial Creative Collaboration

Christine Platt and Catherine Wigginton Greene on the Challenges and Benefits of Co-Authorship

Though Gwendolyn Brooks once said that “writing is a delicious agony,” one might assume that writing with a friend would be more delicious than agony, right? Well…it’s complicated.

It is well-established that writing a novel is no easy feat, and coauthoring a work of fiction with someone you know doesn’t make the task any less daunting. In fact, there may be moments when co-writing a book with a dear friend might even make the process a bit harder. And when that co-writing team includes one Black woman and one white woman trying to write about race and racism, the agony can begin to outweigh the delicious.

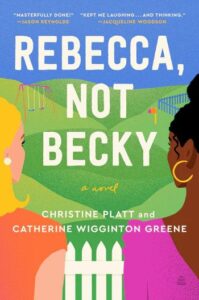

Despite the inevitable stress, we—Christine Platt and Catherine Wigginton Greene, coauthors of Rebecca, Not Becky—knew we could do it. And we did! And through the process, we learned a lot about ourselves as writers, women, and above all, friends.

Before we get to the good part, let’s get to the brutal truth: it was hard as hell.

There is no magic formula for how to coauthor a novel. Before we began, we asked two fellow writer-friends, Jason Reynolds and Brandon Kiely, to give us advice on how they managed to write the award-winning All-American Boys. Given the subject matter of Rebecca, Not Becky, as well as our similar racial dynamics as friends, we imagined we’d face many of the same challenges.

What can emerge in both the individual and collective wondering…is the potential for much stronger connections among us.

“Well, I can’t tell what will work for you two when it comes to the process,” Jason said. “But I can tell you this. No matter what, your friendship comes first. No. Matter. What.”

Every set of coauthors has a different process: Some write their individual chapters and then swap and read before moving on to the next part of the story. Others write side-by-side, offering each other real-time input. And then there are authors who co-create a chapter outline, complete with character arcs and plot points, before disappearing into their respective corners to write without interruption until they’re finished. We tried variations of all the above.

Many months of agony ensued.

We could tell you how many versions of the book’s chapter outline we wrote, but that would be more embarrassing than helpful. Let’s just say outline-writing became a principal tactic for trying to figure out what we needed to agree on before we wrote complete chapters we’d later have to scrap. Even though we talked about what we’d envisioned for the story, the repetitive outline process, although tedious, showed us just how different our perspectives were when it came to manifesting our visions on the page.

For example, in an early version of the novel we’d discussed the women becoming fast friends. But when it came time to write our respective chapters, we realized that only Becky was anxious to be De’Andrea’s friend. And that it made the story read and feel more realistic. In another version, we agreed the Parent’s Diversity Committee meeting should be contentious. And that because it was being written from De’Andrea’s perspective, it could allow readers to get an understanding of what Black parents think and feel when they’re the “only ones in the room.” But ultimately, the scene we wrote was so intense, it was jarring for even our Black editor at the time. So as our outline strategy progressed, we came to better understand how to use it for our benefit. It allowed us to see not only where our characters’ lives needed to intersect but also how to use our respective chapters to move the plot forward.

There was one thing that we did agree on early in the process–that we wanted to use a more complex dual narrative approach. Rather than have our characters experiencing unrelated realities, we felt it was important for readers to see, De’Andrea Whitman, a Black woman, and Rebecca “Becky” Myland, a white woman, living separate lives in parallel. But could we really show how race informs the ways we experience, interpret, and process the same information and events differently? Could we do so without sounding preachy? And without compromising the integrity of the story, the seriousness of the subject matter, and more importantly, our friendship?

We knew we had to try. As writers and educators, we know that fiction is a powerful tool to teach history, empathy, and tolerance. It allows readers to have a bit of cognitive dissonance, a healthy detachment that is more akin to a “calling in” than a “calling out.” Rudine Sims Bishop’s widely accepted philosophy that diverse books are windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors for young readers is also true for adults. We knew that Rebecca, Not Becky would invite readers to see how people from different racial backgrounds might experience the same situations in completely different ways. But we also saw the book as an opportunity for us to educate, entertain, and engage readers so they could ask themselves a critical question: why are we experiencing these situations so differently?

It’s in the conversations we have with one another that we can make meaning of these issues together.

That’s truly where we hope De’Andrea and Rebecca, along with their families, friends, and neighbors in their fictional suburban town of Rolling Hills, Virginia, take us: to a place where readers can ask themselves why. Not with judgment. But with curiosity. Why is Rebecca so determined to make a Black friend? Why is she so focused on making sure her kids aren’t racist? Why does De’Andrea struggle with trusting white women? Why is she so worried about her daughter’s safety in such an affluent neighborhood? What in their past experiences brought them to this moment where they feel they finally have to confront these questions? And in witnessing Rebecca and De’Andrea’s journeys, what might readers begin to grapple with as they think about how their own journeys have shaped them?

We still don’t have all the answers to these questions. We suspect readers won’t either. But that doesn’t mean we stop asking, seeking, and reflecting. Because what can emerge in both the individual and collective wondering—rather than the search for certainty—is the potential for much stronger connections among us. Which is why we’re so excited for our book to be out in the world sparking conversations. It’s one thing to read about race and racism from an academic text or listen to a workshop on the topic from a teacher or workshop leader—and to be clear, we believe in the importance of those—but it’s in the conversations we have with one another that we can make meaning of these issues together. We expect conversations about this book to feel uncomfortable at times, but we also know that on the other side of those tough conversations is the potential for both personal and systemic change.

Whenever we told our networks what we were attempting to do with our first co-authored novel, Rebecca, Not Becky, we’d be asked, “Are you sure?” Or even more direct, “Are y’all out of your mind?”

Maybe not entirely “out of our minds,” but perhaps optimistically audacious. And as Rebecca, Not Becky enters the world at this particular moment, we’re becoming more convinced that audaciousness is exactly what’s needed to change the conversation about race, womanhood, and community right now. And that’s one part of the coauthor experience we’re actually proud of.

__________________________________

Rebecca, Not Becky by Christine Platt and Catherine Wigginton Greene is available from Amistad Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Christine Platt and Catherine Wigginton Greene

Christine Platt writes literature for children and adults that centers African diasporic experiences—past, present, and future. She holds Bachelor and Master of Arts degrees in African and African American studies as well as a juris doctorate in general law. She currently serves as Executive Director for Baldwin For The Arts.

Catherine Wigginton Greene is a writer and filmmaker whose storytelling focuses on strengthening human connection and understanding. Her feature documentary I’m Not Racist . . . Am I? continues to be used throughout the US as a teaching tool for starting racial dialogue. A graduate of Coe College and Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, Catherine is currently pursuing her doctorate from The George Washington University’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development.

Platt and Wigginton-Greene both live in Washington, DC.