Writing Characters in a World After the Repeal of Roe v. Wade

Ashley Wurzbacher on the Complexities of Creating a Pro-Choice Novel Today

I began writing How to Care for a Human Girl not long after Texas senator Wendy Davis’s thirteen-hour filibuster to block an anti-abortion bill that would have shut down 37 of Texas’s forty-two clinics. I was living in Houston, studying writing and women’s studies, and reproductive justice and the craft of fiction lived side by side at the front of my mind.

I wanted to write a novel that would explore the private, difficult, and dignified process of reproductive decision-making for two very different women: older sister Jada, a married psychology PhD student who has an abortion near the beginning of the book, and younger sister Maddy, a nineteen-year-old free spirit, a mess, and, decision-wise, a wild card.

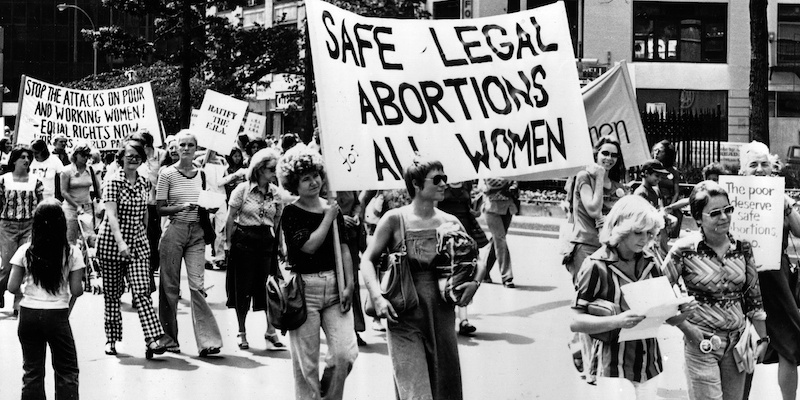

As Davis pointed out that distant evening in her pink tennis shoes, the abortion debate has long been fueled and dominated by men—and women—who consider women’s bodies and decisions to be dangerous, uncooperative, uninformed, and in need of control. As I wrote against the backdrop of the relentless attacks on reproductive rights that transpired from 2014 – 2022, control was the thing I wanted most for myself and my characters. I didn’t realize that writing about this control would mean giving up so much of my own.

*

Writers love to wax philosophical about the special magic that occurs when their characters come to life and assume control of their own fates. The ubiquity of this experience among writers is a documented psychological phenomenon. In a 2003 study, psychologists Marjorie Taylor, Sara D. Hodges, and Adèle Kohányi found that ninety-two percent of writers surveyed experienced what they call the “illusion of independent agency,” or “the sense that the characters are independent agents not directly under the author’s control.”

Writers in the study described their characters as doing things like “argu[ing] with the author about the direction the novel is taking and their actions in it” and even “sleeping in [the author’s] bed with [them].” Many of the writers also described feeling that their characters often “actively resisted [their] attempts to control the story.”

That the novel writing process is at its best when it’s unplanned is a fact that not only chafed against my personality, lifestyle, and prior writing experience but also felt especially unpalatable as I witnessed the decline and fall of Roe v. Wade.My former teacher, Robert Boswell, frames the issue of writerly control (or the lack thereof) in terms of a “half-known world.” Good writing happens when the writer “remain[s] in the dark,” proceeding from a place of half-knowing; we shouldn’t fully know our characters before telling their stories but should let them reveal themselves along the way, creating new and surprising narrative possibilities in the process. Our job is not to control our characters, but to listen to them.

But I don’t like the dark. The idea of ceding control to characters that (let’s be honest) do not exist, and to a story of which (let’s be honest) I am the author never quite made sense to me. It seemed to imply that a certain go-with-the-flow personality was required in a writer, that my more “Type A” orientation made me unsuited to the task.

It also seemed to clash with the material realities of the writing life for myself and other writers not gifted with independent wealth, as a dearth of money and time can make it difficult to wander through fictional forests waiting for their creatures to speak to you; you tend to feel like you can’t afford to half-know. I preferred the experience of writing short stories, whose sharp focus and narrow scope make the writing process feel more manageable.

That the novel writing process is at its best when it’s unplanned is a fact that not only chafed against my personality, lifestyle, and prior writing experience but also felt especially unpalatable as I witnessed the decline and fall of Roe v. Wade. Writing amid and about the precariousness of reproductive freedom, I wanted the right to plan. I wanted control. I wanted the illusion of independent agency—but I wanted it for myself.

*

But when writing a novel, and particularly when writing about Maddy, I could not avoid the dark. I could not maintain control over such an expansive narrative or such a difficult character. Pregnant Maddy was a problem from the start. She was impulsive, reckless, and she had no idea what she wanted. She didn’t have a steady job or supportive relationship. She rebelled against the guidance of her older sister, Jada, and she rebelled against my efforts to herd her toward a particular conclusion.

While Jada was secure in her politics, Maddy was malleable, confused, subject to the influence of others who think they know what’s best for her. Her body and mind became a battleground on which the politics of choice played out, and as such, her decision felt loaded with significance.

My determination to write a pro-choice story meant that I spent a lot of time puzzling over what a pro-choice (or pro-abortion) story was. If a goal of my book was to normalize abortion, did that mean that neither of my characters could have a baby, lest I fall into the Good Girls Avoid Abortion trope? Did it mean that my protagonists needed to be “strong female leads” who both have proud and liberatory abortions and experience no complicated feelings about them whatsoever? Or would a double-abortion story line be a form of protesting too much, insisting too defensively or conspicuously on the acceptability of the decision?

What would I be “saying” through Maddy if she chose to keep her baby? If she chose adoption, would she—or I—be pandering to Amy Coney Barrett and other conservatives’ narratives of adoption as an “idyllic fairy tale” and viable substitute for legal abortion? Could I just call an audible and give Maddy a convenient miscarriage?

Early drafts of the novel were preoccupied with these questions. In the same way that Jada and Maddy worry over how their choices will be perceived by others, I worried over how they would be perceived by readers, who I knew would want to see their politics affirmed by my novel. It’s only human, I suppose, to want this affirmation. Whether it was my responsibility as a writer to grant it was another question.

*

Letting a rigid ideological stance determine the course of a story is generally going to yield a bad story, even in a moment when rigid ideological stances are in vogue. In “Politics and Art in the Novel,” Boswell argues that “any political novel that merely reiterates or embodies an existing ideology is not a work of art…[but] merely the handmaiden of the ideology, a servant to theory, and this servitude usually comes at the expense of believable characters.”

All the same, I feared that the nuance I valued in good literary fiction could come across as an equally damaging and dishonest form of bothsidesism. Was I writing a book that someone was going to hate no matter what I did, telling a story about characters someone was going to hate no matter what choice they made? Quite possibly.

The experience of worrying over this prospective rejection, while uncomfortable, ultimately helped bring me closer to my characters and gave me the perspective I needed to write about them empathetically. In early drafts, Maddy was implausibly immature—one draft even contained a scene in which she had to be removed from a baby swing with leg holes after getting stuck in it—because I was determined to reserve for myself the authority to decide what she should do.

It was only after many drafts and eight years of wandering through the darkness that Maddy and her decision became clear to me in the way the writers in Taylor’s study described: she spoke for herself. The key to her decision lay not in the world around me, but in the actions she’d taken and the qualities she’d displayed in the book’s latest drafts. What mattered was not what her choice “meant” or how anyone felt about it, but that it was authentic and consistent with who she was and what she needed.

That this necessary ceding of control in my art corresponded with a tragic blow to my control over my body via the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision is an irony I’m still not sure what to make of.It was magical to see Maddy grow into her independent agency, even if that agency was only an illusion. It was also an important step in my development as a writer. In slowly and painstakingly writing my way to a place where I could grant Maddy autonomy, I had finally relinquished my control. That this necessary ceding of control in my art corresponded with a tragic blow to my control over my body via the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision is an irony I’m still not sure what to make of.

*

Three months before I turned in my final draft, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization revoked the constitutional right to an abortion, leaving abortion laws in the hands of the states. In Alabama, where I now live, the fall of Roe triggered the “Human Life Protection Act,” which criminalized abortion in the state without exceptions for rape or incest.

This development prompted another wave of self-consciousness: was my novel appropriately ferocious? Would watching characters make free choices seem quaint or outdated in a world in which so many people had just been robbed of the ability to freely choose?

Maybe. Maybe not. In the end, I hope the book I’ve written is pro-choice in the purest possible sense: it depicts women undertaking the work of making stigmatized choices. In giving those characters the independent agency to be flawed and human, I hope it insists upon the dignity of choice even when it’s fraught or messy. What can a writer do but give their character space to assert her agency, to choose for herself? What can a human being do for another but offer this space, in love, without judgement?

______________________________

How to Care for a Human Girl by Ashley Wurzbacher is available via Atria Books.