Writing Away the Angel in My Bedroom: On OCD

Cynthia Marie Hoffman on the Manifestations of Anxiety

The angel had been with me for nearly four decades, and it was my fault he was gone.

I was 36 when I started sharing the secret of my lifelong history with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) beyond my closest family and therapist. My writing group was meeting regularly at my dining room table.

Every few weeks, I served a plate of chocolate layer cookies, and I brought my poems about counting window frames, blinking star patterns on people’s faces, being excessively afraid that my house would explode. When I read them to the group, it was the first time I’d said some of those things out loud. But within the safe circle of my writing peers, I tentatively, bit by bit, opened the floodgates.

And then the angel showed up on the page. I brought him to group for the first time in a poem simply called “The Angel.” I brought his hulking, broad-winged glow. I brought my fear, my lying in bed, immobilized. My quilt with its tiny pink flowers. His standing silence.

The angel first materialized in my childhood house, which had closet doors that swung open and folded like wings. Counting to four kept the angel pinned to the closet door. If I didn’t count, or if I lost my concentration, he’d be free to step across the room, lean over my bed, and whisper into my ear the Secret of Heaven. What that was I didn’t know, and I didn’t want to know. I slept with one ear pressed to the pillow and the other covered with the quilt. I didn’t dare move, no matter if I was sweating under that blanket, no matter if my arm went completely numb.

The angel stayed my entire childhood in that room, and when I grew up and moved out, the angel came with me—to college dorms, apartments, the townhouse, and finally the home I bought with my husband and where we built our family. Every room I ever slept in had a closet door, and when the lights went out, the angel sizzled into place, a towering presence thickening into being.

I never told anyone, not even my father when he crept through my room to use the adjoining bathroom, trying not to wake me. He’d pass unknowingly straight through the angel, momentarily darkening the glow with his navy-blue pajamas, but it always reappeared bright as ever, as does the moon once a cloud has passed.

I was too young then to articulate what was going on in my mind. I had never heard of OCD. And no one else seemed to think an angel was standing in their bedroom. No one else seemed to be drawing patterns in their mind on the windowpanes or tapping their toes inside their shoes, left right, left right. I felt utterly singular and irreparably flawed. Shame is a powerful silencer.

So is fear. During the day, a brand-new anxiety could pop up at any moment. When a car passed, it occurred to me the window would roll down, a gun would appear, and I’d be shot in the head. Suddenly, I thought I’d stab my eye out with the classroom scissors. I flinched at everything. But at night, the angel was there—glowing, ominous, steady. Not exactly a comfort. Not exactly an imaginary friend.

I wasn’t particularly religious, but growing up in church and Sunday School had surely planted a seed. Angels in the Bible often terrified those they visited just by appearing. “Fear not” appears in the Bible 365 times; one for every night of the year. What if, because I had felt afraid at night for no discernable reason, I’d conjured a reason? And if the angel was not a figment of my imagination, could he be really real?

In my writing group, it didn’t matter if the angel was real or not. When we spoke about him, we spoke in the language of poetry. The angel on the page became a “figure,” so that even as we sat at the table, and darkness fell upon the house, and the real angel waited upstairs, we weren’t talking about him. The angel figure lived on the page, and the page was under my control.

I wrote a version of the speaker in the poems—me but also not me—who was brave. This version of me gets out of bed to follow the angel through the closet door and into the house he lives in, which is not my house. She looks at his face for the first time. He has no mouth from which to whisper secrets. His face is shimmery, slick as the inside of an oyster shell.

I wrote the figure as guardian angel. A version of me tells him everything she is afraid of, and he holds each thing in his arms—the deep end of the pool she might drown in, the skyscraper she might fall from. I wrote about the time I’d wanted an angel costume so badly I sat at my mother’s feet for days while she whirred at the sewing machine. I wrote a version of the angel who turns his back down the center of my childhood street, leaving tracks in the snow, and doesn’t return.

Vanquishing the angel from my bedroom showed the control I could gain over all my thoughts.

And then the angel was gone. The real one. I can’t pinpoint the exact moment the angel left my room, but it was sometime during the period of writing these poems. I didn’t notice the absence at first. I just knew that all those years, the air by the closet door had a different pressure. There had been a presence bulging there. And then, one night, just like that, I realized the space he had occupied was no different than the air in the rest of the room.

The emptiness was a shock. I hadn’t thought the real angel would ever leave me. I certainly hadn’t thought I would miss him. And I felt strangely guilty. If I had conjured the angel into being in the first place, then maintaining his presence in my room must have required a sustained concentration that I had committed to all those years. But writing these poems had shifted my focus away from the angel pinned to the closet door and toward the angel on the page. I had been distracted. I had let him down. And at some point, quietly and without fanfare, the angel had slipped through an opening in time and space and zippered up the night behind him.

I found myself staring at the closet door as I lay in bed. A tiny bulb on the fire alarm cast a faint light from the ceiling. On the darkest of nights, when I thought I saw someone standing there, it was just the deflated human shape of my white robe on the hook.

Sometimes a fear becomes a companion the longer you live with it. The angel had accompanied me when I’d felt the most alone, all those years I was harboring my secrets. And now, I had to find out who I was without the angel. It made sense that I would still be looking for him.

The word “angel” appears 46 times in the book I wrote about OCD. Not quite one angel for every week of the year. Not all the angel poems I wrote made it into the book. But the exercise of writing was worth more than the poems I got out of it.

Vanquishing the angel from my bedroom showed the control I could gain over all my thoughts. The more I wrote about my OCD symptoms, and the more I understood that I wouldn’t trigger car accidents or drive-by shootings with the magical power of my thoughts—nor could counting to four prevent them—the less they scared me.

I also discovered I could conjure the angel into my room. Sometimes I do it just to see if I can. All I have to do is think about the angel, stare into the space by the closet door until the air grows dense and the familiar glow appears.

Whether I’m calling a visitation from a real angel or tapping back into the power of my childhood imagination, I don’t care. Revisiting the angel is a way to revisit my younger self. For a moment, I can comfort that girl cowering under her quilt by showing her how far she’ll come. I show her my magic trick.

There’s a prickle of static by the closet door. Then I get a thrill, a spark of fear, and dash to the bed and cover my ears. There’s something inexplicably comforting about it.

______________________________________

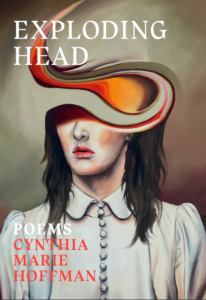

Exploding Head by Cynthia Marie Hoffman is available now via Persea Books.

Cynthia Marie Hoffman

Cynthia Marie Hoffman is the author of five poetry collections including forthcoming Exploding Head.