Writing a Novel Through Illness: On the Inseparability of Body and Mind

Cai Emmons on Her ALS Diagnosis and Writing as a Reflection of Health

In the winter of 2021, I completed a new novel within days of receiving a diagnosis of an untreatable terminal illness (ALS). The novel was written quickly—more quickly than my novels usually take and more quickly than I “approve” of writing a novel. It emerged like come Coleridge-like opium-induced rush of an idea that insisted on being chronicled, sprung from Trump outrage and pandemic isolation, both of which banished my left-brain, vetting, editor-self into obscurity.

The new novel is impossible to categorize, and, as such, I was quite sure it was unpublishable. It seemed to come from the unfettered, unschooled brain of a child still incapable of distinguishing dream and fantasy from reality. The story demands a leap of faith from readers, and I didn’t think most readers would want to take that leap. (Apologies for evasiveness here, but I’m trying not to include any spoilers.) I knew the piece was something I had been compelled to write, and it had been useful in keeping me occupied during the pandemic, but I sensed that I would be shelving it. Nevertheless, I sent it to my agent.

As I waited to hear back from her, the diagnosis came in. Not a surprise. A huge surprise. The deterioration of my voice over the previous year had been a conundrum to doctors. We had considered and discarded one diagnosis after another. Meanwhile, I had watched my speech become slower and more garbled. But it was such an isolated symptom that it didn’t occur to me to think of it as life-threatening; my limbs were fine, and I was still hiking and cross-country skiing and doing yoga.

I revisited my novel as I waited to hear from my agent. The diagnosis exposed the work in a new light. This piece of writing, I suddenly saw, had been served up by a body beginning to break down, a body that knew something was wrong. The novel could only be read as a metaphorical chronicle of my developing illness, an autobiography of the last year, despite the fact that there is not the least bit of discernible autobiography within its pages.

I write with a pen on a pad of paper, not exactly a whole-body experience, but one which requires a certain amount of coordination of hand, wrist, and fingers. I think of hand-writing as a more corporeal experience than writing on a keyboard, though that, too, requires coordination of wrists and digits. If hands are writing tools, how does the rest of the body figure into the writing process? Sitzfleisch is the German word for the ability to sit for long periods of time. I know some writers who can sit for hours without moving, but I am a fidgety person and can only sit still for so long before I must rise and wiggle. Often it is in the periods where I’m moving, talking a short walk or doing some yoga stretches, that my synapses seem to be jumpstarted, and I am flushed with new ideas or solutions to problems that have stumped me.

The body and the work. The body of work. The work of the body. Of course they are linked, but how? Have all my novels been “served up” by my body’s concerns as much as this recent novel has been?

The murky relationship between mind and body has eluded philosophers for millennia. Are the mind and body separate entities as Descartes believed, or are humans seamless unitary organisms as Spinoza and the current materialists believe? (I am simplifying this conversation grossly.) Current brain research by neuroscientists and the work being done in artificial intelligence adds data to this question, but still no clear answer.

We know the mind can exert influence over the body. Research show that athletes can improve performance by visualizing what they will do in advance, essentially conducting mind rehearsals. The muscles benefit from such imagining and performance is improved. Other clear evidence of the mind’s power over the body is the well-documented placebo effect that has long been understood as an aid to healing. But we tend to focus less on the ways things work in reverse. How do bodily functions influence our thinking?

When my son was young I often said my preeminent task as a mother was “mood management.” What that meant was making sure he had enough sleep, regular nutritious meals, enough water, enough time to run wild. If I took care of those things, he was happy and ready to learn, and our days went smoothly. We all have similar empirical experience of being unable to think clearly if we’re under-rested, or famished, or in pain. We can attempt to override the messages that we should slow down, relax, rest, or eat, but the culture encourages us to believe the mind/brain can forge on alone, independent of a ragged body.

Orwell wrote his dark novel 1984 when he was becoming sicker and sicker with TB. He was “coughing up blood, struggling for breath, wracked with fever and wasting away,” John L. Ross says in Shakespeare’s Tremors and Orwell’s Cough. Orwell himself said, “Writing a book is a horrible exhausting struggle, like a long bout with some painful illness.” How much of that novel was offered up to him by a body wracked with disease and needing to express itself?

Laura Hillenbrand, who suffers from debilitating chronic fatigue syndrome, wrote Seabiscuit and Unbroken during the years when she was too weak to leave her house. Unbroken tells the story of a World War II hero who endured a plane crash, floated on a raft for 47 days, then survived two and a half more years in brutal Japanese POW camps; this story, too, might be read as a metaphor for Hillenbrand’s own struggle against a nearly insurmountable illness.

I hear shouts of agreement: Of course the work of these desperately ill writers was affected by their physical aches and pains. Of course that would color the work. But are you ready to make the next leap? To imagine that all writing, even that of ostensibly healthy individuals arises from the internal realm of the body, its rhythms and secretions, its harmonies and arrhythmias?

I have examined my own earlier work, wondering if this could be true of what I wrote before this recent novel. My first published novel, His Mother’s Son, was written when I was mothering a young child. I obsessed over things then that I’d never thought of before. I worried about my son getting hurt; I worried about him hurting others. When he was bitten by a dog, I wanted to kill that dog with a ferocity I associated with mothers protecting their children in war-torn countries.

As a mother it was my biological imperative to protect my son. Looking back on that novel now, I see how my body served up that subject too, my “mind” quickly corralled into collaborating with my body’s need. I am trying not to describe this in a binary way, but I find it nearly impossible to resist this mind/body dualism, because the Cartesian notion of mind and body as separate has become so central to Western thought. I don’t have the language for discussing this subject as I believe things truly function: mind and body so integral to one another they cannot be separated.

Recent research into the human gut biome has found this region of our bodies to have such an impact on our overall health and well-being that it has been dubbed “the second brain.” Emeran Mayer, one of the pioneering researchers into the gut biome lays out some astonishing facts in his book The Mind-Gut Connection: How the Hidden Conversation Within Our Bodies Impacts Our Mood, Our Choices and Our Overall Health. The gut with its millions of bacteria, functions like a second command center, with its own nervous system, the enteric nervous system, and with the largest supply of serotonin in the entire body. The vagus nerve serves as the conduit between this command center and the brain stem. 90% of the transmissions travel from gut to brain; only 10% travel from brain to gut. None of this is entirely surprising. Long before we understood the science behind the gut biome, people discussed having strong “gut feelings.”

I can’t speak for all writers, but most fiction writers I know do not go seeking ideas actively; ideas seem to descend on us, surrounding us in a heady ether, challenging us to bring them to light. But I wonder now if this sense of an idea’s arrival doesn’t originate in a place that is well beyond cerebral control, not external but deeply internal, subject matter arising from the wisdom of the microbial colonies in our guts, and spreading into the swill of blood and organs and muscles, finally making its way to our brain synapses, insisting on a voice.

__________________________________

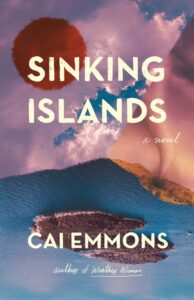

Sinking Islands by Cai Emmons is available now from Red Hen Press.