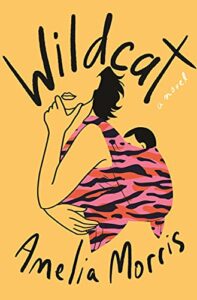

Writing a Mother Character Who Can “Run With the Wolves”

Amelia Morris on Female Archetypes, Mean Girls,

and Clarissa Pinkola Estés

When I started writing my novel, Wildcat, I was thinking a lot about mean girls—generally. Of course, I was also thinking specifically about Mean Girls, the Tina-Fey scripted 2004 film. Mean Girls famously deals in the realm of female teenagers, whereas Wildcat focuses on grown women—mothers, in fact. But somehow, this age difference didn’t seem to matter, which made me start to wonder how to define the archetype of a mean girl, exactly (an insecure female with power?) as well as its male equivalent (a bully?).

It was early 2016, and I’d just had my second son. One of my best friends had previously sent me Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ bestseller, Women Who Run With the Wolves, in which Estés writes, “When women hear those words [wild and woman], an old, old memory is stirred and brought back to life.” In childbirth, I felt like I’d come in close contact with this Wild Woman Estés was describing and understood the ways in which, as Estés wrote, she’d appeared “to be outlawed by the surrounding culture.” In particular, Wild Woman seemed to have no place in American motherhood, which brings us to the ultimate female archetype: The Mother.

What you need to know about her—The Mother—is right there in the word and the way we use it; to mother a child is to be mothering, whereas the phrase “to father a child” doesn’t carry the same sense of ongoing connection and “to be fathering” simply isn’t something we say. Adrienne Rich points this out in her definitive work Of Woman Born: “The meaning of ‘fatherhood’ remains tangential, elusive. To ‘father’ a child suggests above all to beget . . . To ‘mother’ a child implies a continuing presence.”

The culture I was so steeped in as a new mother seemed to be persistently, almost invisibly, telling me that motherhood was an interminable domestic activity—the opposite of wild. Its fiscal value: less than zero. One day, I came across a hip clothing website trying to sell me socks in the color they’d deemed “Mom pink.” It was an anemic Pepto Bismol.

“To ‘father’ a child suggests above all to beget . . . To ‘mother’ a child implies a continuing presence.”

I resented this. In some essential way, I had never felt more powerful. I had made a human being and was sustaining it via my own body. But on the playground, us “mamas” (or nannies, always female) spoke to each other via our children, telling him or her to share, to give up their swing for the next child in line. To play nice! In late 2016—The Art of the Deal, “grab ‘em by the pussy,” “lock her up”—I was tired of everyone expecting Mommy and her children to be perpetually soft in a world that felt endlessly hard.

The story I wanted to write was one of a woman caught between archetypes: Mother meets Wild Woman meets Mean Girl, with modern-day Los Angeles as the backdrop. Another line from Rich’s Of Woman Born propelled me: “The worker can unionize, go out on strike; mothers are divided from each other in homes, tied to their children by compassionate bonds; our wildcat strikes have most often taken the form of physical or mental breakdown.” That one hit close to home. I’d broken down so many times since becoming a mother, and never in the company of another mother or potential ally.

But what if a mother could publicly strike? I began to imagine what that might look like as well as who or what would be on the receiving end. Of course, I needed some characters. Enter Leanne, our protagonist and Mother. The jacket copy on my book says that Leanne has “lost her way,” but in Clarissa Pinkola Estés-speak, we would say that Leanne has been separated from her wildish nature. This has left her “meager, thin, ghosty, spectral.”

If Leanne managed to access her wildish nature, who would she chase? Enter Leanne’s ex-best friend, aka Mean Girl, thematically named Regina. Regina isn’t in touch with her wildish nature either, yet she does not appear meager, thin, ghosty or spectral. Instead of a copy of Women Who Run with the Wolves, she has latched on to the well-known platitude that “well-behaved women rarely make history.” Regina is that friend of yours who gets an eye twitch when you tell her about something good that happened to you—who believes vulnerability is death, but hasn’t also realized that vulnerability is life.

I was tired of everyone expecting Mommy and her children to be perpetually soft in a world that felt endlessly hard.

In an interview, the writer Lauren Oyler described autofiction as “any fictional work that creates explicit confusion or conflation between one of the characters, probably the main character and the author.” By this definition, Wildcat is autofiction. Leanne and I share a very similar biography: we are both writers, mothers, with dead fathers and Republican mothers, but I chose to write it as fiction so that Leanne could be braver than me. Wilder.

Also, instead of leading Leanne to suffer a physical or mental breakdown alone, as I had done, I could give her an ally—someone grounded in a more spacious, open-hearted reality. Enter Leanne’s newest friend, Maxine. Maxine, in many ways, is Wild Woman. She is that friend that offers you warmth and coziness when you don’t feel deserving of it. She’s that friend who seems to have read all the Brené Brown books, but never actually mentions Brené Brown to you. She is patient. She is secure and self-aware. She is the mother you always wanted but never got.

“If a woman is shunned,” Estés writes, “it is almost always because she has done or is about to do something in the wildish range, oftentimes something as simple as expressing a slightly different belief or wearing an unapproved color.” (“On Wednesdays we wear pink.”)

Leanne and I share a very similar biography, but I chose to write it as fiction so that Leanne could be braver than me. Wilder.

When I became a mother, I could feel that the proper—the accepted—way to do it was to be small, selfless, and ever-present. And for the most part, I fell in line. I quit my low-paying job and stayed home with my babies. Schlepping the stroller and all the baby accoutrements, I often felt like those Pepto Bismol-colored socks.

But the good thing about being a writer is that you don’t need to feel powerful to do it. You need time and a bit of space—and just for clarity, I’m not one of those writer-mothers who can work during their kids’ naps. No. I needed to be away from them. (“To adjoin the instinctual nature does not mean to come undone . . . It means to establish territory.”)

The Word document that held Wildcat became my territory. And there, I began to play, to leap up and give chase. I began to ask questions I wanted answers to, like: What happens in a world when being a mother doesn’t evoke a whitewashed domesticity? What if our society understood that being a mother meant being a person with a sense of self? A person who had ambitions and who didn’t want to pour them into her child as though creating a bizzarro proxy self? And what if this parent (with a self) felt responsible for not just the health and wellbeing of her biological kids, but her neighbors’ kids as well?

What would happen, I wondered, if Martha Stewart Living, or the equivalent cultural landmark for a traditional home life, booked Wild Woman for a feature story? What if the complicated and messy could somehow triumph over the flat and shiny?

What would the world be like if being a mother conjured an image of a lion secure in her domain? If the hip clothing site sold socks in the style of “Mom Stripes” and they were orange and black? What would happen in a world where Mommy’s cage door swung open?

__________________________________

Wildcat by Amelia Morris is available now from Flatiron Books.

Amelia Morris

Amelia Morris is the author of the blog, Bon Appétempt (named one of the twenty-five best blogs of the year by TIME magazine) as well as the memoir by the same name. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, McSweeney’s, The Millions, and USA Today. She is also the co-creator of the podcast, Mom Rage. She lives in Los Angeles with her family.