Write Like a Girl: On Learning to Break Free of Literary Gendered Expectations

Sanjena Sathian: “Moving between identities is what I most crave as an artist. And it’s also all my characters want.”

The first stories I ever wrote, in elementary school, were through the eyes of what we once called “tomboys”: short-haired girls who climbed trees and scraped their knees and cantered horses through forests in rainstorms—girls who cried only in private; girls like Jo March and Scout Finch and Pippi Longstocking; girls who resisted their girlhood, or whatever the world told them girlhood was.

When I got older, my narrators changed from figures resisting girlhood to people unconstrained by femaleness at all: I started writing men. Angsty young men inspired by Holden Caulfield; arrogant male detectives in the vein of Hercule Poirot; depressed alcoholic men like Nick Carraway. The first short story I submitted for publication was about a repressed white male professor; the first to be anthologized was about a conservative male bureaucrat.

When I wrote my first novel, Gold Diggers—a partly autobiographical story about my childhood growing up in the suburbs of Atlanta—I chose to revisit my own life through the eyes of a boy: a 15-year-old horny nerd named Neil who grows into a 26-year-old man child.

Part of me felt that, in order to be taken seriously as a woman writer writing women, I would need to adopt the apparent female voice of the moment.

I didn’t think much of my slight bias toward male POVs. Fiction writers are supposed to be able to inhabit characters who are materially unlike us, filling in those people with parts of ourselves, and letting our curiosity about other ways of being handle the rest. Still, while on tour for Gold Diggers, I could always count on someone to ask: Why did you write from the perspective of a teenage boy? Implicit in the question was an assumption: masculinity must have been harder for me, a cisgender woman, to access than womanhood. But here’s the strange thing: it wasn’t. I liked being a man on the page. The problems all started when I tried to be a woman.

*

I have never been a teenage boy, but I did grow up, as we all do, in a man’s world, and I learned from a young age to mimic masculinity. As a high school debater, I practiced deepening my voice to avoid sounding shrill—a sin in the persuasive arts. I could hear my own arguments more clearly if I switched into man-mode, borrowing confidence and charisma. After tournaments, my throat often ached, as though rebelling against the voice I’d forced it into for 72 hours.

When I became a novelist, my artistic process mirrored my debate life. I initially spent several years trying to write Gold Diggers from a female perspective, but the prose came out breathy and sentimental, never funny or authoritative. While writing a teenage girl, I felt trapped in my past, writing from a place of pain and confusion. Locating Neil’s voice was like pitching into that old faux-baritone: it estranged me from myself so I could see my material anew. Becoming Neil on the page made me who I wanted to be: a novelist with command of her domain, a person in charge of their own story. Neil helped me in part because he was, as Zadie Smith has described first person narrators, “the I who is not me”—but also because he was a man.

After finishing Gold Diggers, I felt drawn to a new project that required a female perspective. I wanted to write what I imagined as a 21st century version of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca: a story about two women who become entangled with the same charismatic man at different points in time. The women would become obsessed with one another from afar, their interrelation bordering on the surreal. I wanted to capture the uncanny sensation of leaving a bad relationship, then later being unable to recognize the version of yourself who was once in that relationship. I decided to level up the absurdity of the conceit by using my own name—the women would be named Sanjana and Sanjena—to comment on the slipperiness of female selfhood. I was apprehensive: being a woman on the page, especially a woman named Sanjana or Sanjena, would, I assumed, mean being more nakedly myself than ever.

But when I started writing, I lost steam. The first problem was my voice. As Neil, I’d let myself sprawl, drafting lengthy sentences, thick paragraphs, long chapters. By contrast, in my new project, my sentences were staccato, my paragraphs and chapters fragmentary, the narration almost opaque, as though I was erasing myself. The voice signaled character problems: as Neil, I’d allowed myself to write what people sometimes call an “unlikeable” character; I didn’t care about charming the reader, and I let Neil satirize and critique as he saw fit. In the new novel, I was more tentative, as though afraid that this narrator might lose the reader’s sympathy if she—I—said the wrong thing.

As I was writing the book, fragmentary and minimalist novels by women were in vogue. I admired many of them, such as Jenny Offill’s Dept of Speculation, as well as their progenitors—Marguerite Duras’ The Lover and Renata Adler’s Speedboat. In Lauren Oyler’s novel Fake Accounts, the narrator meets a writer who describes this contemporary vignettey style as “distinctly feminine,” a product of mothers dashing off whatever they can in between childrearing tasks.

Fragments, of course, are not inherently female—see: David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King or David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress—but Oyler’s point stands. Women were fragmenting themselves on the page, and the literary world was loving it. Part of me felt that, in order to be taken seriously as a woman writer writing women, I would need to adopt the apparent female voice of the moment. It was like trying to fit in at a party where I knew no one, anxiously hoping a gaggle of (mostly white) women writers might invite me into their clique.

Inevitably, my approach failed. All I had done was adopt embarrassingly retrograde ideas, acting as if “woman” meant one essentialized thing and “man” another. Worst of all, my own misogyny led me to label the authoritative and funny parts of me “male,” and the vulnerable parts “female.” All these problems accreted, ultimately manifesting in the manuscript. When I handed the first 150 pages to early readers, one of them told me they missed Neil. Where had he gone? Where had I gone?

I took a few months off, and when I returned to the novel, I noticed the same problems with the narration. But I also realized that the voice issues were causing a subsequent story problem. It wasn’t just that I’d tricked myself into believing that I could only be funny or opinionated when writing as a man. I’d also approached my material differently while writing as a woman. I’d deprived my female characters of self-knowledge, indeed of their very selfhood. Both Sanjana and Sanjena were defined in relation to the main male character, Killian, enthralled and shaped by his charisma. This was supposed to be their novel, but I’d ceded the text to him.

Initially, I’d explained it this away: I was writing about a time in my 20s when I’d had little agency in a bad relationship, when I had not known “better.” But Gold Diggers was about an even younger person—a teenager—who also lacked complete knowledge of the world. In that case, I’d used basic literary tools like a retrospective narrator to endow narrator-Neil with the faculties character-Neil lacked. Why did I believe Sanjana deserved any less?

I would no longer write about two women being erased by one man; I would write about two women in themselves.

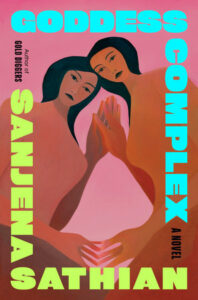

Often, when I’m stuck on a project, I eventually realize that the craft problem blocking my path is itself a problem for the characters in the text. As a writer, I was grappling with what it meant to be a full, actualized woman on the page; that now became the defining preoccupation of the book—a novel I eventually titled Goddess Complex. I would no longer write about two women being erased by one man; I would write about two women in themselves.

As I set out on this new version of the project, I began reading and re-reading novels with new urgency, seeking literary companionship. I turned to other fictional women, preferring more loquacious and capacious narrators to the opaque, minimalistic voices I’d been mainlining during my anthropological study of women writers. Female narrators, a mix of old and new influences, filled my head, forming a chorus, like friends: the hilarious Esther in The Bell Jar; the ornery Cassandra in Dorothy Baker’s Cassandra at the Wedding; the lonely Ruth Puttermesser in Cynthia Ozick’s The Puttermesser Papers; the fierce Lucy in Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy; the cerebral, artistic Edie in Raven Leilani’s Luster; and one woman sprung from the mind of a man—the brilliant unnamed protagonist of Norman Rush’s Mating, whom Rush based on his wife, Elsa.

I turned to these fictional women not because they “represented” strong women in some instructional manner but, rather, because their voices were fully alive. Reading them altered my voice—the length of my sentences, the acidity of the prose—and sharpened both the narrative and the aims of the novel. Thanks to this POV, I finally felt free to write the real story, abandoning the book I thought I should write, as a “female writer,” and uncovering the novel I wanted to write—one not solely about the erasure of the self but also about self-discovery. I realized that I had done my narrator Sanjana a disservice, leading tentatively with the thing that might make her sympathetic—the wounds left by a bad relationship. I’d flattened her in a way I’d never done to Neil.

So, I tried to see her as she was. I ventured past the abstract trauma of a bad relationship and toward something more precise: the experience of a woman ambivalent about childbearing, whose husband desperately wants a baby, and who must fight both him and her own multifaceted desires to understand herself. The more I drafted, the more marginal the male character, Killian, became. He’d initially been a domineering man controlling not just my characters, but also my actions as the author. Now he shrunk into a hapless fool, important to but not the source of the whole story, which was ultimately about women. My partner, who always reads my work, told me that I was finally “letting it rip.” Ultimately, Goddess Complex became a riskier, stranger, more specific novel—and a more honest one.

My sophomore novel is now entering the world, and I’ve started a new project. I’m not writing in first person, this time, but instead trying my hand at a third person, multi-POV novel, in which half of the POV characters are men and half are women. In part because of all that grappling with my “female” voice, I’ve felt freer this time, bobbing and weaving between scenes in men’s varsity wrestling locker rooms and women’s 1960s consciousness raising sessions. Moving between identities is what I most crave as an artist. And it’s also all my characters want—to express their selfhoods fully, to be irrevocably themselves.

__________________________________

Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian is available from Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Sanjena Sathian

Sanjena Sathian is the author of the critically acclaimed novel Gold Diggers, which was named a Top 10 Best Book of 2021 by the Washington Post and longlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. It won the Townsend Prize for Fiction. Her short fiction appears in The Best American Short Stories, The Atlantic, Conjunctions, One Story, Boulevard, and more. She’s written nonfiction for The New York Times, New York Magazine, The Drift, The Yale Review, and NewYorker.com, among other outlets. She’s an alumna of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has taught at Emory University, the University of Iowa, and Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. In spring 2025, she will serve as the Ferrol A. Sams Jr. Distinguished Chair of English at Mercer University. Goddess Complex is her second novel.