Women on the Verge: The Jazz Age Origins of Burnout

Marsha Gordon on Ursula Parrott’s Ambitious Women

“I have a theory,” the recently-rediscovered writer Ursula Parrott mused in a late 1920s letter in which she wonders if she should accept an advertising position at Arnold Constable’s Fifth Avenue store, “that it’s perfectly possible to manage a job, and one other thing, well,” but no more than that. “The trouble usually is that one tries to manage job, and about four other things, and three of them go wrong.”

Reading this letter while I was researching my recently published biography, Becoming the Ex-Wife: The Unconventional Life & Forgotten Writings of Ursula Parrott, I pictured a typical hour of my life as a University professor: sending emails and responding to texts, working on an article after grading a paper, scheduling a talk in another state while planning what to make for lunch.

My attentions, as Parrott observed before the technology was in place to ensure that no moment in our lives is truly focused, are perpetually divided. My mind races from the moment I wake up as I try to do all of the things I need to do, knowing that the cracks will show: as typos, forgotten appointments, burnt leftovers in the toaster oven.

Ursula Parrott, Boston born in 1899 as Katherine Ursula Towle, was Radcliffe educated and lived her adult life—including four marriages and divorces—largely in New York City. Women of her generation had, for the first time in American history, entered the workforce en masse in the 1920s, during which time the number of working women dramatically increased. This notable uptick of women entering the workforce did not significantly taper off until the post-World War II era.

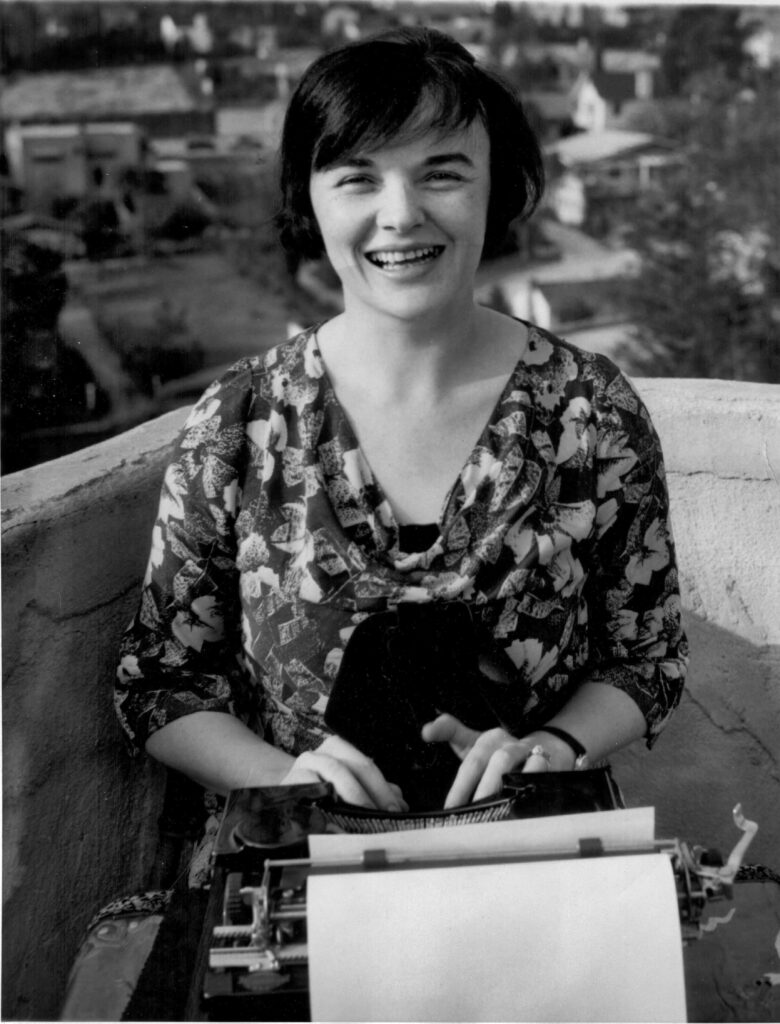

Ursula Parrott in Hollywood, CA, May 1931. Associated Press Photo.

Ursula Parrott in Hollywood, CA, May 1931. Associated Press Photo.

Parrott was among the first wave of college educated, working women—many of them single by choice, widowhood, or, like her, divorce. After leaving a demanding job writing advertising copy to dedicate herself to becoming an author in late 1928, Parrott came to the conclusion that she—and women like her—could really not “have it all,” to borrow the mantra Helen Gurley Brown popularized many decades later, in the 1980s.

Starting with “Leftover Ladies,” a nonfiction treatise that Parrott published in 1929 alongside her sensational, semi-autobiographical bestselling novel of the same year, Ex-Wife (republished by McNally editions in May 2023), she wrote about how impossible it was to be a successful career woman and have a successful marriage and be a parent and travel and maintain one’s health and figure and keep up social obligations, “simply because there is a limit to the amount of vitality a woman has to expend, altogether.” The independence that a career afforded also had a cost.

Parrott came by this knowledge honestly: over the course of her wildly successful publishing and screenwriting career, which, as Jessica Winter recently discussed in The New Yorker, continued into the late 1940s, she singlehandedly supported her family—including her son, and her never-married older sister who helped her care for him—while discovering that she rarely had the time or energy to enjoy much of life outside of work.

*

In Ex-Wife, Patricia (like Parrott) lands a position as “assistant advertising manager, within one step of having a secretary of my own.” Her days consist of phones ringing “twenty times an hour” with a barrage of requests and demands. She describes “That feeling of running, of having been running endlessly, so that I was breathless, yet must go on running forever, seemed to sum up my life. Running through days of posing as an efficient young business woman, through nights of posing as a sophisticated young woman about town.” Pat knows that this life is unsustainable, but as a self-supporting divorcee, with hopes for another shot at middle-aisling, what other choice does she have?

Another divorced character in Ex-Wife argues that women “can have a career, letting it absorb all emotional energy (just like the convent).” But since there was only so much vitality a woman has and so few hours in the day, few could “stand the pace of a career and a great love affair.” This was another facet of the work-life balance problem that Parrott dramatized: in her stories, a successful career almost always doomed women to unhappiness or loneliness because men could not accept being outpaced in income or status by their girlfriends or wives. Across the body of Parrott’s writing, this situation was inevitable since women always excelled at their professional pursuits.

Parrott’s serialized novella, Breadwinner, published in Redbook from October 1933 to February 1934, tells just such a story: “of a girl whose life gets caught up between the two millstones of emotion and ambition.” Linda, a widowed mother with an ascending career as a screenwriter, reflects on how exhausted she is in every installment, often more than once. Her talent earns her more writing assignments, promotions, and salary increases.

She works ten hours a day, rushing home after work to dress and go out with her beau, Mark, who complains about her “gaudy career,” which he greatly envies, of course, especially after he loses his job. During a fight, he makes a hurtful accusation: “You love me in the time left over.” I can’t imagine a male character saying this line to a female character in a novel from even just a decade prior.

Here and elsewhere, Parrott saw that careers took time and energy away from relationships, especially spousal and parental—and this loss was especially consequential, even punishing, for women. At the end of Breadwinner, Mark runs off with Linda’s young niece, who chastises her aunt on her way out the door: “Managing being happy with a man like Mark is a full-time job. It can’t be done in fifteen minutes now and then snatched from the picture-business or the play-writing business.”

*

Though most city-dwelling women of Parrott’s generation did “women’s work”—teaching and nursing, sales work or clerical support in shops and offices—others pursued careers that required even more of their time, with demands that crept into lives that had, in earlier generations, been largely limited to domestic labor. In 1928, New York’s Department of Labor reported that an astonishing 48 percent of married women in Binghamton earned wages outside the home, more than twice the national average for cities with a population of more than 25,000.

Parrott saw a double edge to this sword: there was something secure and peaceful, if limiting and boring, about the lives of women of her mother’s and grandmother’s generations, who had been protected from outside-the-home drains on their time and energies and cared for by husbands who felt morally (and legally) obligated to stay the marital course.

In her 1935 novel, Next Time We Live, Parrott reframes the conversation about women entering the workforce by imagining a pair of sympathetic, career-hungry characters, Cicely and Christopher, who both attain top places in their respective fields. But work necessitates that they live on different continents, with Cicely, who works constantly, raising their child essentially alone.

Twelve years into their only occasionally in-person marriage, Cicely goes to Italy to visit Christopher, who is on the verge of dying from tuberculosis, that disease chosen by so many authors to dispense with their female heroines. She delivers the novel’s final, melancholic line: “Next time we live, Christopher, we’ll have time for each other.”

Parrott does not present Cicely’s career ambitions as the cause of their relationship’s unusual configuration. In fact, there is no blame in the novel; just an acknowledgment of what happens when unrelenting professional ambition pulls two mutually-adoring characters in totally different directions. Next Time We Live is a novel of futility in which careers suck the air out of marriage and family.

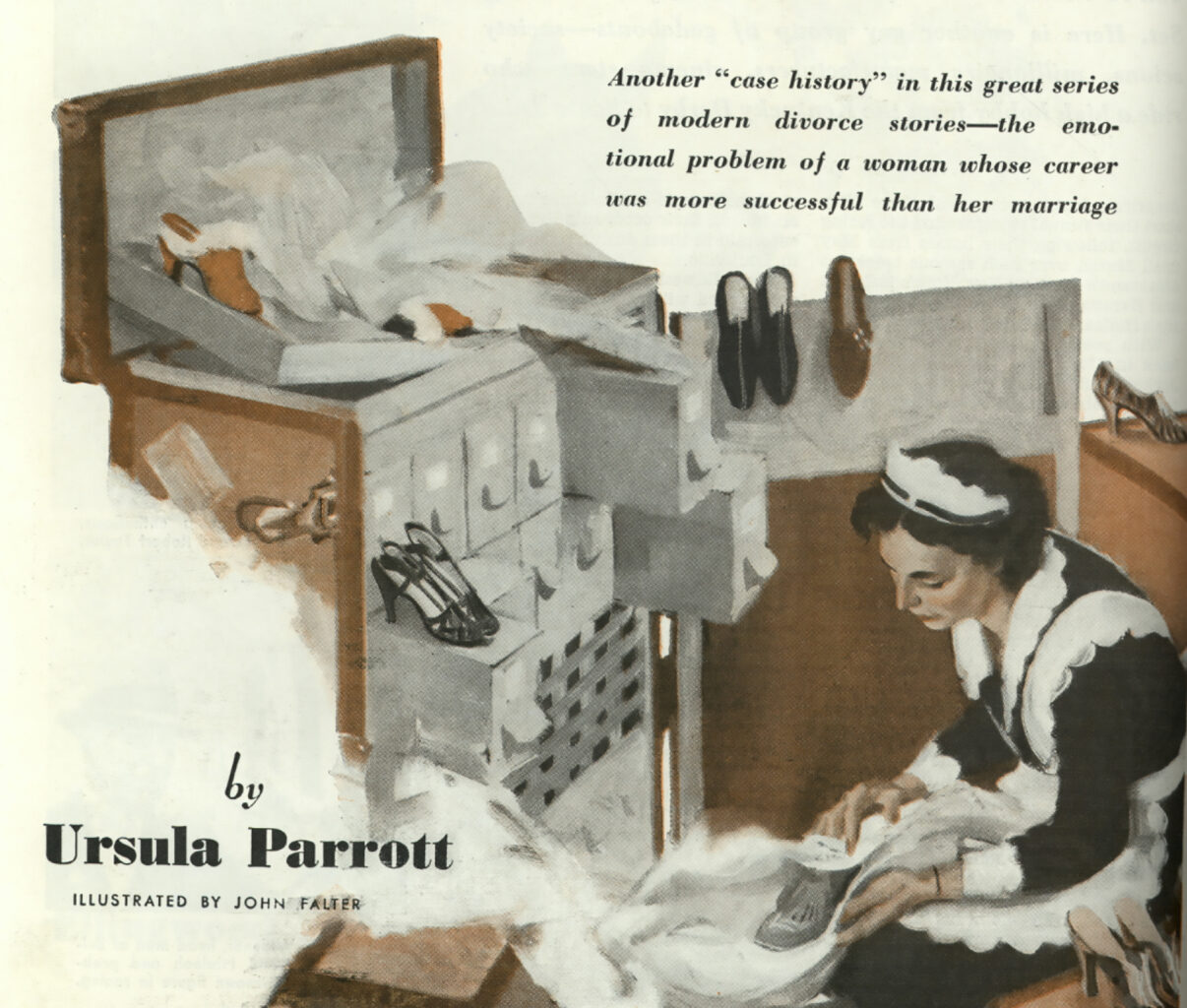

“Grounds for Divorce: Nonsupport” was one of a quartet of stories Parrott wrote on the subject of divorce for Hearst’s Cosmopolitan. This one, published May 1938, delved into one of Parrott’s favorite themes: women who were more successful than their husbands, and the negative impact of this imbalance on their marriages.

“Grounds for Divorce: Nonsupport” was one of a quartet of stories Parrott wrote on the subject of divorce for Hearst’s Cosmopolitan. This one, published May 1938, delved into one of Parrott’s favorite themes: women who were more successful than their husbands, and the negative impact of this imbalance on their marriages.

Parrott created similarly bleak scenarios for career woman across dozens of her tales. In Grounds for Divorce: Nonsupport, published in May 1938 in Cosmopolitan, a biology professor can’t keep up with his wife’s successful singing and film career, propelling them towards divorce on the grounds of non-support. In the aptly titled You Ride Success Alone, published as a Redbook serial in the fall of 1938, an aspiring painter who never gets anywhere in his career is paired with a woman who becomes a tremendously successful journalist.

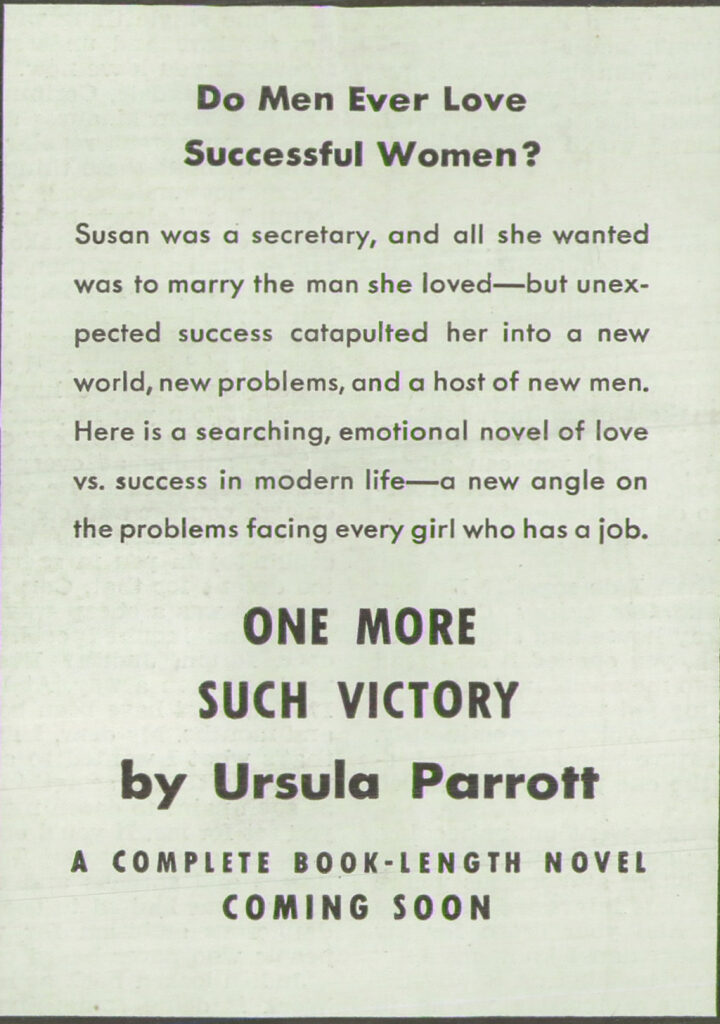

Despite her willingness to materially support his unpaid artistic pursuits, his insecurity, resentment, and envy compel him to leave her. In One More Such Victory, published in Cosmopolitan in February 1942, a woman’s successful writing career overshadows her lover’s career and becomes the sole reason for their relationship’s undoing.

When Redbook published Parrott’s appropriately titled “You Ride Success Alone” in their October 1938 issue, the story’s tagline made it clear that the idea of the “career woman” was firmly in place.

When Redbook published Parrott’s appropriately titled “You Ride Success Alone” in their October 1938 issue, the story’s tagline made it clear that the idea of the “career woman” was firmly in place.

Parrott’s career women put on good faces as they run themselves into the ground, trying their best to appear to be keeping it together as they drag themselves out of bed for another day at the office. These women put on masterful performances, keeping their suffering largely to themselves. They often drink too much, as Parrott did; like so many of her generation, she struggled with alcohol abuse to cope with the unsustainable pace of life.

The summary for Ursula Parrott’s “One More Such Victory” gets right to the point about the story’s overarching question: “Do Men Ever Love Successful Women?” Hearst’s Cosmopolitan (Aug 1941).

The summary for Ursula Parrott’s “One More Such Victory” gets right to the point about the story’s overarching question: “Do Men Ever Love Successful Women?” Hearst’s Cosmopolitan (Aug 1941).

Several months before she became a best-selling author who would spend the next two decades writing as much as she could (she published twenty novels and over one hundred stories, serials, and essays), Parrott had the kind of idea that often comes after a night of ample cocktails. Half joking but fully “bunned,” as she liked to say, she told her lover at the time that she had finally figured out a “CAREER” for herself: “Open a speak-easy for tired business women,” which she dreamed up “when I wanted to go have a poured dinner, and couldn’t think of a place where I wouldn’t be stared at.”

Her mock business proposal went on to describe “the Woman’s Speak-Easy” as having “all the worst features of a pub and a tea-room. Serve chicken patties and sweet cocktails (Alexanders probably) and have a ward for those who passed out,–and a lethal chamber for those who got sick… I’d run that.” The best part was that she “could drink up all the profits.”

Parrott has not been read or taught in classrooms for many years. But I hope that her surprisingly relevant tales, now almost a century old, find their way to a new generation of readers, especially women who are still struggling, and I think largely failing, to figure out how to avoid the particular variety of burnout that afflicts women, which Parrott perceived as a side effect of the “equal everything”—sex, booze, morality, work—Jazz Age.

________________________________

Becoming the Ex-Wife: The Unconventional Life and Forgotten Writings of Ursula Parrott by Marsha Gordon is available now via University of California Press.

Marsha Gordon

Marsha Gordon is Professor of Film Studies at North Carolina State University, a former Fellow at the National Humanities Center, and the recipient of a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar award. She is the author of numerous books and articles and codirector of several short documentaries.