When I was young, we kept a wolf in the basement. It was a compromise, where one of my parents wanted no wolf and the other wanted the wolf in the living room, and so together they came up with this solution. The wolf lived six steps down from the rest of us, and when we let him out it was from the very back door, the one that faced the forest.

At first I did not like the wolf. I was a cat person. And we already had a cat—a longhaired, skinny thing, at times willing to let you touch her. When I did pet Minerva, she gave me a look like, this is niceish, probably more so for you than me. I twirled my fingers under her creamy chin, ran them down her gray back. So would the wolf eat my cat? If the door unlatched and what was upstairs went downstairs or vice versa?

We found the wolf one afternoon on the grounds of an old mansion where we’d gone for a book sale, proceeds of which would go to my mother’s alma mater. We went to this event every year, filling boxes with volumes that cost dimes or quarters. Neither of my parents was profligate, and so the outing always had a feeling of splendor. In the capacious blank rooms, winding lines of books—whole paragraphs of them.

Our boxes were already in the back of the car, and my mother stood off to the side, having a smoke—her arms in an L, like a military hand signal, cigarette wavering in the vicinity of her mouth. She paused, sightline going from middle distance to zoned-in. “Larry?”

Dad was still arranging the boxes for transport, I guess, because he was at this point half tumbled into the back of the car. He got up, hit his head on the car roof, pushed the hatch door down with a solid thwack. “What?” No answer, but my mother’s aura of concentration compelled him to walk over to where she stood. I followed, as did my brother (walking like a clown, as per usual). The four of us stared past a small precipice at the wolf, sitting forlornly near a pine tree where he might have been viewing the book fair but was now, most definitely, gazing at us. He got up, limped two steps, and sat down again, all the while keeping up his plaintive look.

“Wow, a wolf!” I said.

“A wolf, Mommy!” said my brother.

“It looks injured,” muttered my father.

“Let’s go see if we can help,” said my mother, a maniacal gleam in her eye. She tossed the cigarette.

We lived in a town well known for its crafty, can-do spirit. It was a survivalist town, filled with melancholy people, and the sky above was mostly white. In that town and in those years, I saw the sky as a sequence of key shapes. This key, that key, skeleton keys, Medeco keys. Sometimes jumbles, sometimes singular. It was all very intricate, I felt, in my prolonged, or even endless, it can seem now, study.

However, none of us really did have the key, so to speak, or the keys were always soft and amorphous and not ready for one little hole or secret. We labored along in our crafty survivalist lives, performing the act of a family. It wasn’t just an act—of course not. We were a family. And yet as with every family, while there was a tension or magnetic force keeping us close, there was an equal yearning or leaning, like a Shetland pony on a rope, away from the centripetal field.

I was in charge of bringing the wolf his vittles. I used a plastic measuring cup to get his portion out of the garbage can where we ended up keeping the “dog” food, a receptacle until recently used for near-the-laundry trash, fluffs of dryer lint mostly, carrying it downstairs into the dark, wolf-bearing basement. (We’d tried storing the food in the basement, but he’d handily knocked over the can and gorged himself.) I turned on the light at the top of the stairs.

We kept the wolf in the dark, although during the day some light did come in the back door. And of course when my father took him jogging he saw the light, or when my mother, alone in the house, let him out at twelve and three, into the backyard. We’d called our vet soon after we first lured him into our hatchback—a wolf among the books—but our vet, a sanctimonious Catholic, had cautioned us that wolves were illegal, and so if he were really a wolf, we’d need to turn him in. (Turn him into what, or whom?) In any case he himself, God-fearing, etc., refused to treat the wolf. My mother and father did agree, at that moment, on the assholeness of that veterinarian.

We ended up using a sketchy vet from Norwalk—he needed the work.

I flipped the light switch, and this is what I saw: the washer and dryer, a linen chest, an old dresser filled with art and random objects, the pool filter and pump, stored patio furniture, an ancient gray-green carpet. In the middle of the carpet lay Wolfie, his head angled tragically on his now-healed front paw. He jumped up and stood whenever I appeared, half embarrassed, it seemed, to be caught unaware, or in sorrow. Oh, Wolfie—but ours was a stoic town, and we envisioned ourselves as stoic people.

I put the bowl down and watched expressionlessly as he padded toward the food. He was small for a wolf, and even weeks after his capture he still had a bit of a limp. He was a black wolf, which is unusual I’ve been told. Perhaps he was a Russian wolf. He would have looked good in the snow, in a snowy field. I went back upstairs, to the crunch of vittles.

One day about four months later—after school ended anyway, because I was waking up late (the sky a brighter white than on school mornings)—I looked out the window and saw Wolfie and Minerva both free in the yard.

The wolf and the cat were staring at each other. Wolfie lunged, his body blurring into an italic, and Minerva lunged too, becoming more of a dash. Within two seconds Wolfie was barking at the chain-link fence and Minerva stood on the other side, tail bristled out, looking at him with scandal and dull horror.

Some mornings I watched as my father and Wolfie walked down the driveway on their way out for a run, my father’s bright blue running shorts like an Olympic sprinter’s, and Wolfie with his patient padding paws, and the white sky overhead, and the crunch of gravel.

My father would soon be gone, but for what seemed like forever he was right there, in the driveway or in the kitchen or in his office (also in the basement, a small room off the central area). Both parents gave up smoking, and I started smoking. At Thanksgiving, we set aside some dark meat for the wolf. Plans were hatched, grades were dispensed, fights were had up and downstairs. My brother became excellent at sports. We lost some but not all of our relatives.

On the last day my father ran with the wolf—it was an early summer evening—I turned away from the window and sat on my bed. My room was a box lined with Laura Ashley wallpaper and decorated with one peacock feather. Minerva declined my invitation to be petted. My mother was downstairs doing something inscrutable. My brother was at baseball practice.

We all escaped that town eventually, even Wolfie.

Still his shape remains with me, his shape like a shadow or an outline or someone’s scribble. I remember his grieving face when we first saw him, sitting at the edge of the field by the old mansion, with all the people buying books very near, getting back into their Datsuns and Peugeot wagons, and the tranquil way he let us take him—meaning, said the sketchy Norwalk vet, that he was very under the weather indeed. He got better and better in our basement, and as he got better he must have realized where he was, didn’t he? I remember bringing him his portion of food, and I remember his moments of freedom—his mysterious runs with my father, the foreshortened hunt involving Minerva or the occasional squirrel. Some days I’d see him padding around the edge of the yard along the chain-link fence. Then he’d lie down, staring with his black eyes in his black face under the white sky.

I was growing up, I guess. So was my brother.

In the afternoons I sat on the stairs between the first floor, where Minerva lay unmolested, and the basement, where Wolfie slept close to the door. His fur did not shine. Some hours, he slept with his eyes open. The light from the door came in brief streaks and squares, easily dissuaded. Darkness was a dust storm to make our way through, a forest road to run down.

Originally published in the Mississippi Review.

__________________________________

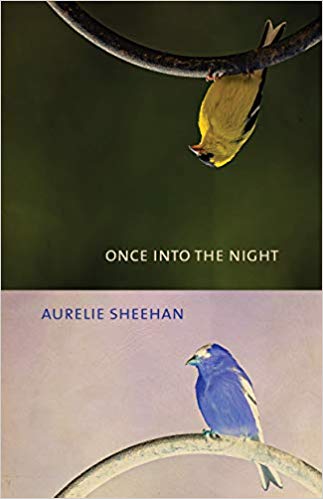

From Once into the Night. Used with permission of FC2. Copyright © 2019 by Aurelie Sheehan.