With Pandemic Information Overload How Can We Tell What is Real?

Terrence Holt on Common Distortions and False Equivalencies

“When the brain is hurt by an accident, or the mind disordered by dreams or sickness, the fancy is overrun with wild dismal ideas, and terrified with a thousand hideous monsters of its own framing.”

–Joseph Addison

We know next to nothing. That’s how we feel. SARS-CoV-19, or “the novel coronavirus,” the pathogen responsible for this pandemic, is a strikingly unusual beast, capable of wreaking a bewildering variety of harms on the human body, ten times deadlier than pandemic influenza, and spreading through Earth’s unprotected population in a way no pathogen has done in our lifetime. But perhaps the most striking thing about all of this is our overwhelming ignorance.

No one is helping us. That’s how we feel. Innocent actions, like collecting the daily mail, now come fraught with questions (Can I touch this? Should I wash that?), even as the mail itself contains bills that may not be payable. This gap between what we know and what we need to know gets filled, as all vacuums do, variably. The news media do what they can, but their ability to translate the technical language of science, especially biomedical research, has always been hampered by a tendency to miss the finer nuances. Now, at a time when those nuances really matter, we’re seeing repeated instances where, between the pre-review publication of breaking research and the rolling cycle of online news platforms, between the expert testimony offered at press conferences and the evening news, things get distorted.

All we really know for certain is that the reality of the pandemic has been lost behind a fog of confusion, uncertainty, and doubt. Without a consistent national policy, we’ve all had to become our own policy analysts. We may not know all the facts of this new disease science is just beginning to study, or be equipped to understand, much less critique, the conduct of that research. What we can make sense of, however, is just how the results of that research are presented to us—the rhetoric shaping what we are being told, the ways information is distorted.

Given the massive failure of any central authority to assume responsibility for what are literally life-or-death decisions, those decisions are now up to each of us. But how do we decide wisely, given the rhetorical fog clouding so much of what we’re told? I offer here a brief guide to some of the distortions shaping the fog of bad news.

*

The Framing Effect (or the Argumentum ad Ignorantiam)

Often these days we hear medical experts say “there’s no evidence.” They might better say “we don’t know.” Same difference? Not really. It’s all in how you frame it.

In the popular ear, the formulaic “there’s no evidence” suggests more than it usually means.

“We have no evidence for….” You can complete that sentence with any number of CoVID-related concerns. Early on, and most notoriously, it was the utility of masks. “There is no evidence masks protect against the spread of disease.” Such pronouncements were taken to mean “masks don’t help.” The advice came not so much from uncertainty about their effectiveness, however, but from overwhelming certainty that there weren’t enough masks to protect healthcare workers. One of the prime directives of evidence-based medicine is that you don’t expose people to risk without evidence of some greater benefit. When agencies such as the WHO and the CDC initially recommended against universal wearing of face masks, the rationale was that, without evidence such widespread use would make a difference in stopping the pandemic, it seemed unwise to expose healthcare workers to the risk of running out of essential equipment. But the reasoning got buried behind the too-terse “we have no evidence”—period. As the state of the supply chain and of our knowledge changed, so did the recommendation, to promote general mask-wearing. That change was widely viewed as a reversal, evidence that the experts don’t know what they’re talking about, and taken as an excuse to flout other evidence-based recommendations.

John Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Detroit Institute of Arts

John Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Detroit Institute of Arts

In the popular ear, the formulaic “there’s no evidence” suggests more than it usually means. It suggests that somewhere a group of scientists has conducted a rigorous test, in which masks were tried, and they failed. But when a medical person says “there’s no evidence,” it can also mean (as it did in this case), that at this point no such studies have been done. There’s just no evidence, one way or another. A more straightforward statement might have been, “We don’t know.”

The different ways people hear “there’s no evidence” versus “we don’t know” constitutes what logicians call a “framing effect.” When it came to masks, people didn’t know how to interpret the scanty information they were given, and applied the wrong frame (somebody tried and found masks don’t work), so that now we have people pulling guns on each other in WalMart.

Guns in WalMart. My own rhetorical tropes here—the slippery-slope, propter hoc, and amplificatio—produced in a final non sequitur that imaginary display of firearms. A more straightforward statement might have been: We can probably agree that, had the guidance been clearer, masks wouldn’t have functioned quite so readily as an interpersonal flashpoint. The shift from an arresting image to that qualified statement loses the grab of rhetoric, but that’s why the shift is so important. It is precisely the power of rhetoric to steamroll over nuance and complication, allowing us to pull out (rhetorical) pistols, that’s at issue here. All argument is rhetorical; the danger is when rhetoric takes over and enforces its own logic on a set of facts not yet fully established, and harder to understand because the rhetoric has pre-empted our access to them. Especially at this time it is imperative we work to refuse the insistence of rhetoric in ourselves as much as in others.

Framing errors require a step back. They are hard to see. Even harder might be the related ad ignorantium,which involves seeing what we don’t know. A case of the ad ignorantium appears in the frequent items warning us all that infection with SARS-CoV-19 does not confer lasting immunity. There are reports from clinics of people getting CoVID twice, and of laboratory studies that seem to show “waning immunity,” as antibody levels decline after infection. This is taken to mean that vaccines will not work, and the pandemic will never go away.

This is perhaps the most virulent form of framing error, possibly because the frame isn’t simply misplaced, as it was in the case of masks, it’s just gone. Basic facts about virology and the immune system simply dropped out of the discussion, allowing nightmares to fill the gaps in our knowledge. The New York Times has recently attempted to provide some of the missing context. Almost all viral infections confer lasting immunity. Antibody counts normally fall after an infection clears while immunity persists. And those cases of repeated infection? Coronavirus can persist in some people for many weeks. Negative CoVID tests in the middle of persistent infection are far more likely false negatives (at least one fifth of all negative tests are likely false). To recognize that rhetoric can substitute for knowledge is important: in the absence of information, we are drawn to believe certain stories, encouraging or frightening, for reasons having less to do with reason than with our own irrational needs.

*

The Undistributed Middle (or the Non Distributio Medii) and the Appeal to Emotions (Argumentum ad Passiones)

The debate about reopening the schools is so heated, a discourse of shame and blame, because it often relies on the failure to distribute the middle: it seems to present you with two all-or-nothing choices: either we’re in a deadly pandemic within which conventional schooling is unacceptably dangerous, or by taking the proper precautions we can safely reopen our schools. This is the ultimate force of the undivided middle: it not only spares us from the difficulties inherent to the middle ground, it also presents you with starkly limited, impossibly absolute, alternatives. When it also invokes, as this one does, the appeal to emotion, it can be very hard to know where that occluded middle ground actually lies.

Children, especially as they figure in this debate, are an overwhelmingly powerful trope, a symbol understandably loaded, for adults, with emotion. Focusing on the risks of keeping children home can ignore the risk from sending them to school—the latter set of risks not so much to children as to the community. The problem, ultimately, with the appeal to emotion is that it demonizes alternative positions. It is not to minimize the suffering of some children under lockdown to suggest that opening the schools could be terrible for the community at large. The calculus of the pandemic is hard and inhuman. It places us in a world not where there are just two choices, one humane and the other cruel. It puts us in a world where we have no good choices, just many different bad ones.

As an alternative to shame and blame, recognizing the middle ground in the midst of a pandemic doesn’t require a retreat to false equivalence, where we treat all positions as equally valid. In the midst of a pandemic, when we don’t know anything and nobody seems to be helping us, recovering the middle ground could allow us to acknowledge our shared contingency and vulnerability. We are all being compelled by necessities that demand actions whose outcomes we can’t clearly see, and may find hard to live with. Until we recognize the harm our choices will inflict on others, we remain prisoners of our rhetoric.

*

The Reification Fallacy and the False Equivalence (or the Falsum ex Condigno)

This is the domain of the economic argument. People point to readily available numbers—per The Wall Street Journal $900,000,000,000 in lost productivity—to demonstrate the harm done to the economy by the lockdowns of April-May. They argue from there that we must re-open the economy immediately. But numbers like this are meaningful only if you have something to compare them to.

We are in a nightmare, and have been for a long time. But nightmares, like pandemics, eventually end.

One problem with this kind of argument is that it trades in a common form of reification fallacy, treating as concrete that which is not, and eliding the system of values necessary to make any set of numbers meaningful. To what do we compare any economic damage? Estimates of US mortality from CoVID-19 range anywhere from 200,000 to 2,000,000 (algorithms reckoning in the millions assume a disease with an infection mortality rate of 1% and an effective reproduction number of 4, spreading unchecked to herd immunity). Either estimate is staggeringly, inhumanly high—morally incalculable.

What is the appropriate answer to nine hundred billion dollars? How would that many deaths in a 12-month period affect the economy? We don’t know. It’s never happened. Add in the immediate costs of 200 to 250 million people infected, an unknown number needing hospitalization (never mind that in the worst scenarios there won’t be hospitals for them), and then the long-term costs of lingering effects of the disease (unknown), disruption to production and distribution networks (unknown), and the disruption to family and social networks—all unknown or unquantifiable.

Recognizing the attractions of anything that seems to light the darkness might help us to resist the way others manipulate our need for information.

But the real problem with this argument is that it weighs human lives in dollars. This is what we mean by false equivalence.

*

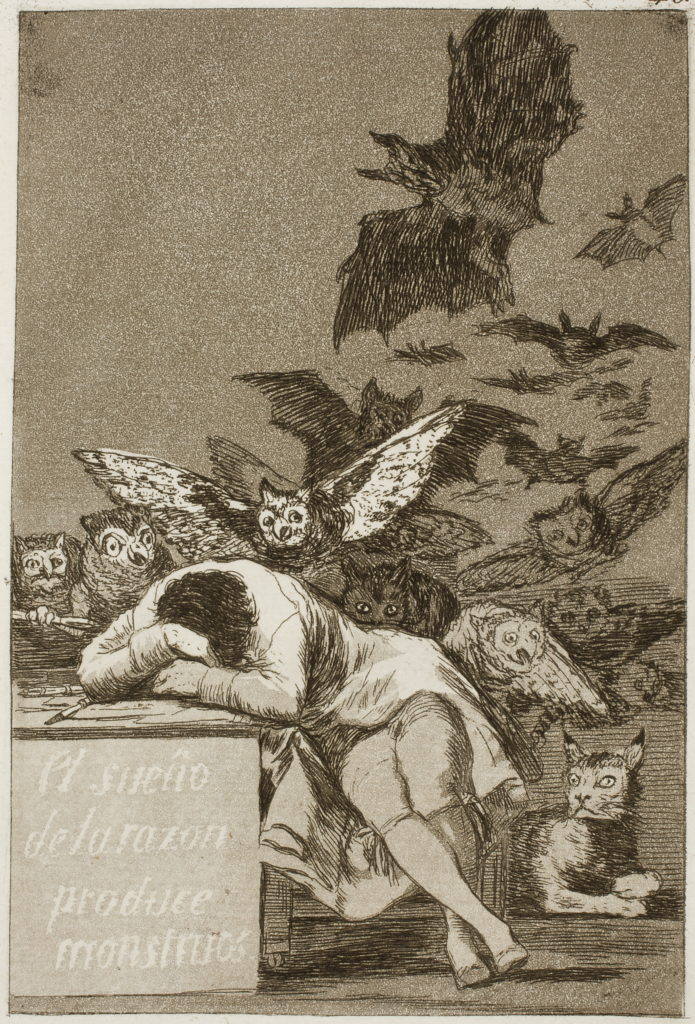

The Sleep of Reason

One question about all this, beyond simply learning to recognize—and possibly read—the distortions currently roiling the public forum, is what does their appearance at this time tell us about the ways the pandemic is changing us? Whether it’s in the mistrust of expert advice, the polarization of the debate between impossible, and often frightening, absolutes, or the way so much of our anxiety has come to focus on loaded symbols, we are in the long middle of something and can’t see the end.

Francisco Goya “El sueño de la razón produce monstrous (1797-1798), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Francisco Goya “El sueño de la razón produce monstrous (1797-1798), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Recognizing the attractions of anything that seems to light the darkness might help us to resist the way others manipulate our need for information, our need for reassurance (or our dark eagerness to be scared). The way our uncertainty has fit so neatly into the polarizing style of the current administration tells us something important. As a society, we were already near so many different breaking points.

We are in a nightmare, and have been for a long time. But nightmares, like pandemics, eventually end. The most important question to keep in front of us, in the long night of the coming months, is who will we be when we wake?

Terrence Holt

Terrence Holt is the author of three books, and is an associate professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.