“Will There Be War in the Morning?” Inside the Home of Italy’s Foreign Minister, August, 1939

Tilar J. Mazzeo on Galeazzo Ciano and His Wife (and Mussolini’s Daughter) Edda

Where is Ciano? Dinner had been cleared away. Galeazzo Ciano had been expected. The houseguests nursed after-dinner drinks. On this last night of August 1939, the air was hot and still even this late in the evening. Just like always in Rome in the late summer.

But the city beyond the walls of the villa was already unrecognizable. Coffee had been rationed since spring. Workingmen paused now for a caffè corretto—a bitter chicory brew “corrected” with grappa. Irate housewives muttered words tantamount to insurrection as they waited in long lines outside shops, only to find there was no beef or butter. Private automobiles were forbidden, and a creaking bicycle passing through an empty street at night brought curious neighbors to peer out of darkened windows.

Something anxious hung in the air. The businessmen in the salon that night knew that their office secretaries quietly kept gas masks tucked away in desk drawers, alongside their powder compacts and lipstick cases. People said to each other privately now that the real shortages were still coming.

Across Rome, all but the most fortunate felt the bite of austerity. In the grand homes of the wealthy and well positioned such as this one, with access to the halls of power, though, only the mood had changed substantially. The guests were gloomy and fretful, and they were focused on just one thing: Ciano.

Everyone in Italy knew Ciano.

Count Gian Galeazzo Ciano—his black hair slicked back and shining with pomade, his clothes elegant; foppish, vain, and ultimately foolish—was the second most powerful man in fascist Italy. He was the son-in-law of strongman Benito Mussolini, as well as Mussolini’s political heir apparent, and as the nation edged closer to the precipice of war that night, Galeazzo Ciano was also still the man in charge of the faltering international relations: Italy’s foreign minister.

A single question held Italy breathless: Would there be war in the morning? Ciano would tell them.

*

Only Benito Mussolini held more power, and war was not what Mussolini wanted, though he talked a good game. Mussolini had thrown his support behind Hitler’s Third Reich, and now, unless the Allies blinked, Italy risked being drawn into a German-led conflict that Mussolini knew Italians didn’t want and its military couldn’t manage. Still, Mussolini was optimistic. The Allies would bluster and moan. They would ultimately do nothing. They had done nothing when Hitler took control of Austria, then Czechoslovakia. They would not fight now for Poland.

*

Galeazzo Ciano was not so certain. In fact, Galeazzo had many doubts both about a war and about the Third Reich.

Since the beginning of the year, Galeazzo had been keeping a diary. The uncensored and indiscreet views he recorded in those pages did not paint flattering pictures of his father-in-law or the Germans. He despised in particular his German counterpart, Hitler’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, a thin, cruel man with unsettlingly pale eyes, whose lust for power and political bootlicking earned him the contempt of nearly all who met him.

The American diplomat Sumner Welles rather undiplomatically remarked of Ribbentrop that “The pomposity and absurdity of his manner could not be exaggerated.” One German counterpart remarked that “One could not talk to Ribbentrop, he only listened to himself ”; another described him as “a husk with no kernel.” Here was the kind of man who plotted revenge simply because another hapless lieutenant’s name was mentioned before his own in some bureaucratic document or another.

Already many in Hitler’s inner circle were eager to see Ribbentrop stumble. His fall from power would be welcome. In the pages of his diary, Galeazzo summed Ribbentrop up in two simple words: “revolting scoundrel.”

Ribbentrop, in return, hated Galeazzo Ciano. He hated the count’s casual aristocratic manner and his unabashed love of the English. He hated that Galeazzo did not feign deference and how he impertinently questioned the wisdom of the Führer. When the time for vengeance came—and he did love vengeance—Joachim von Ribbentrop would take great pleasure in destroying the Italian foreign minister.

If Ribbentrop was, in the view of the Italian foreign minister, a fool and a sycophant, Galeazzo Ciano had no illusions left about Hitler by the summer of 1939 either. Only weeks earlier, he had met with the Führer and returned, he confided dangerously to his diary, “completely disgusted with the Germans, with their leader… they are dragging us into an adventure which we have not wanted… I don’t know whether to wish Italy a victory or Germany a defeat… I do not hesitate to arouse in [Mussolini] every possible anti-German reaction… they are traitors and we must not have any scruples in ditching them. But Mussolini still has many scruples.”

*

Mussolini equivocated. One moment, he was full of talk of war and honor and determined to prove to Hitler that he was as eager for imperial expansion as the Germans. The Italians were the heirs to the Roman Empire. He dreamed of a return to sweeping greatness. The next moment, however, reality pressed on Mussolini. Italy was not prepared for this kind of war, and he railed against the pressure the Nazis were placing on him.

All that day, Galeazzo had been working feverishly behind the scenes to avert disaster and to prevent the conflict in Europe from exploding. A last-minute British agreement to a peace conference with the Germans took all evening to hammer out. It would solve nothing, but it would buy them some room to navigate. By the time Mussolini had been brought on board, Galeazzo was hours late for his dinner engagement.

When he strode at last through the doors of the salon, eager faces turned toward him, and Galeazzo Ciano smiled brightly. He was a showman. This was his stage. They could sleep well, he assured the guests laughing, confident: “set your minds at rest… France and England have accepted the Duce’s proposals.” The British had blinked after all. Of course. Appeasement was once again the word of the hour. There would be no war tonight. The guests chuckled and refilled their glasses before slowly wandering off to their bedrooms.

For a brief moment that night, Galeazzo was as relieved as anyone. It didn’t last. By midnight, the peace was unraveling again. Galeazzo was back in a ministry car, the smartly uniformed driver swerving through Rome’s narrow streets toward an office overlooking the storied Piazza Colonna. Someone passed Galeazzo a sheet of paper. There were quick steps in the corridor. Word was filtering in now over the diplomatic wires. Hitler was having none of a peace conference. The headlines for the morning papers in Berlin were already at the presses, announcing the German invasion of Poland.

By dawn came word that Poland was falling. Galeazzo knew what it meant. Mussolini would not join the Allies. His friendship with Hitler would prevent Italy from taking up arms against Germany. But perhaps Mussolini could be persuaded to remain on the sidelines. In the tragedy that was coming, the only hope was somehow to keep Italy neutral.

*

For nearly a year longer—until June 1940—Galeazzo Ciano and his allies in Rome would manage that feat. Hitler knew perfectly well who he blamed for this stalling in Rome. He would later say of Galeazzo Ciano, “I don’t understand how Mussolini can make war with a Foreign Minister who doesn’t want it and who keeps diaries in which he says nasty and vituperative things about Nazism and its leaders.” Already those diaries were seriously aggravating Hitler.

In the end, Mussolini could not be tempered. He was at once too weak and too proud. Belligerence was too deeply ingrained in his character. At ten, Benito Mussolini had been expelled from school for thuggishly stabbing a classmate. By twenty, he had stabbed a girlfriend. By thirty, he was the founder of the Italian Fascist party, which rose to power by the simple stratagem of systematically murdering thousands of political opponents so there was no one left to oppose him.

By forty, Benito Mussolini had wrested power from the king of Italy through the force of a cult of personality, an act that inspired a younger and admiring Adolf Hitler to attempt a similar Beer Hall Putsch in Germany. Within a year or two, by 1925, he cast aside any pretense and ruled as a fascist dictator, riding a wave of populist support, buoyed by invective and a swaggering rhetoric of nationalism and nostalgia that exhilarated his followers and terrified his critics.

Galeazzo Ciano fought in every way he knew to keep Italy from entering World War II on the side of the Germans. From the rearview mirror of the twenty-first century, that much is maybe even valiant.

Machismo was at the heart of Mussolini’s claim to power. In the world that Mussolini had created, “real men” did not back down from a fight and “real Italians,” men who were heirs to the Roman empire that had conquered the world, conceded to no one. This created a political dilemma that was clear to him: “The Italians having heard my warlike propaganda for eighteen years… cannot understand how I can become a herald of peace, now that Europe is in flames except the military unpreparedness of the country [for which] I am made responsible.” Mussolini did not want war. But he would not lose face either.

*

Galeazzo Ciano fought in every way he knew to keep Italy from entering World War II on the side of the Germans. From the rearview mirror of the twenty-first century, that much is maybe even valiant. For all that, though, it would be a stretch too far to claim Galeazzo Ciano as any kind of hero. He prosecuted other wars, against those far less equipped than France or Britain, with few scruples himself; he was widely and probably accurately considered, like his father-in-law, to have played a role in the extrajudicial execution of political opponents; he enriched himself in office, while much of Italy went hungry; his politics, even when anti-German or anti-Nazi, were not yet anti-fascist. He was, by most contemporary accounts, frivolous, indiscreet in his gossiping, and an incorrigible womanizer.

Joseph Kennedy, then the US ambassador in Rome, observed of him in 1938, “I have never met such a pompous and vain imbecile. He spent most of his time talking about women and spoke seriously to no one, for fear of losing sight of the two or three girls he was running after. I left him with the conviction that we would have obtained more from him by sending him a dozen pretty girls rather than a group of diplomats.” The Americans were not the only ones to draw this conclusion. Galeazzo Ciano’s weakness for attractive women had also caught the attention of the Germans.

*

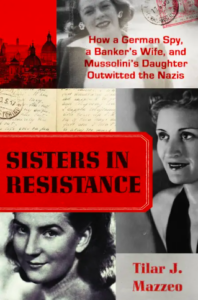

Still more would it strain credulity to claim Galeazzo Ciano’s wife, Edda, as a heroine in this story, although Sisters in Resistance is certainly a book about her and about the astonishing courage, intelligence, and resolve she demonstrated in what was to come.

Edda was also someone known in 1939 to every Italian. She had been known to every Italian for at least those eighteen years of Mussolini’s reign, first as the favorite eldest child of Italy’s autocratic ruler and a young hellion, and then, after the celebrity Ciano marriage in 1930, as the glamorous and flamboyant Countess Ciano. Twenty-eight on the eve of war—September 1, 1939, would be, as chance had it, her twenty-ninth birthday—Edda’s reputation was not a sterling one, and diplomats around the world were very much keeping an eye on her as well.

The British ambassador in Rome, Sir Percy Loraine, reported to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain that spring that Edda “has become a nymphomaniac and in an alcoholic haze leads a life of rather sordid sexual promiscuity.” She drank too much gin and played poker for high stakes poorly. While Galeazzo spoke with a high-pitched, nasal twang and talked endlessly about his passion for antique ceramics—hardly the Mussolini idea of machismo—Edda scandalously wore men’s trousers, smoked, wore makeup, and drove a sports car while her husband rode along as passenger.

While Galeazzo took to bed in a love-them-then-leave-them fashion so many of her aristocratic girlfriends that people in Rome simply talked of “Ciano’s widows,” Edda’s bedroom tastes ran to sporty and fit younger men like the aristocratic Marchese Emilio Pucci, a twenty-four-year-old Olympic skier and keen race-car driver (as well as, later, renowned fashion designer). No one is quite certain when their on-again, off-again liaison started. It probably began sometime in 1934 on the ski slopes in Cortina.

By 1939, Emilio Pucci was back in Rome and once again seeing Edda, though no one supposed that Emilio was her only lover. Why did foreign diplomats care so much about the dissipated life of the Italian foreign minister’s wife and Mussolini’s daughter? Quite simply: her influence with her father. Mussolini doted on his eldest child, and, unlike her husband, Edda was enthusiastically pro-war and pro-German. Galeazzo would later write in the diary that, at the crucial moment in the spring of 1940, on the eve of the invasion of Belgium and Holland:

I saw [Mussolini] many times and, alas, found that his idea of going to war was growing stronger and stronger. Edda, too, has been at the Palazzo Venezia and, ardent as she is, told her father that the country wants war, and that to continue our attitude of neutrality would be dishonorable for Italy. Such are the speeches that Mussolini wants to hear, the only ones that he takes seriously… Edda comes to see me and talks about immediate intervention, about the need to fight, about honor and dishonor. I listen with impersonal courtesy. It’s a shame that she, so intelligent, also refuses to reason.

Italy entered the war at last on June 10, 1940, and threw in its lot with Hitler’s Germany. Galeazzo Ciano saw that it could only end in disaster. Edda conceded that it was a gamble. But Edda, like her father, thrilled to the show of boldness. Danger invigorated Edda. Besides, in the late spring of 1940 it very much seemed to both Edda and her father that Italy was putting its chips on a sure winner: Hitler. It was the first of Edda’s brash wartime gambles. Only after it was too late would she come to understand that the stakes were higher than she had imagined and that trusting Hitler was a fool’s errand.

_________________________________________________

Excerpted from SISTERS IN RESISTANCE by Tilar J. Mazzeo. Copyright © 2022 by Tilar J. Mazzeo. Reprinted by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Tilar J. Mazzeo

TILAR J. MAZZEO Tilar J. Mazzeo is Professeure Associée at University of Montreal, the former Clara C. Piper Associate Professor of English at Colby College, and the author of numerous works of narrative nonfiction. Her books have been New York Times, San Francisco Chronicle, and Los Angeles Times bestsellers.