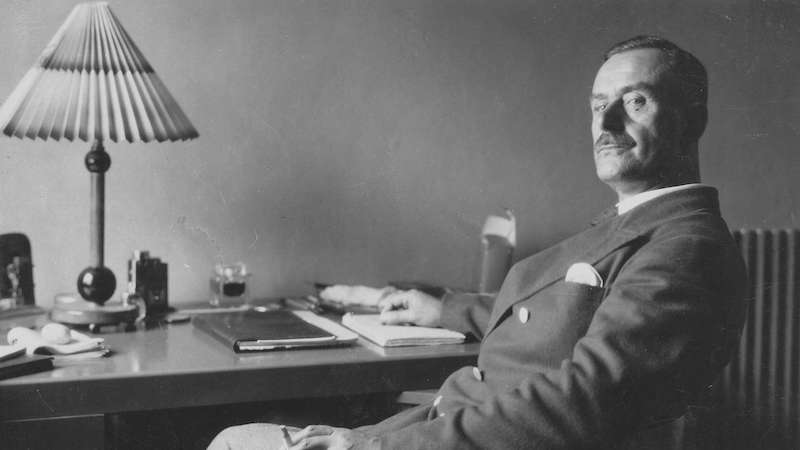

“Will I Come to a Miserable End?” Jenny Erpenbeck on Thomas Mann

"He succeeds in inverting the order of farce and tragedy."

The following is from a speech for the Thomas Mann Prize of the Hanseatic City of Lübeck and the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts. Translated by Kurt Beals.

*

Ladies and Gentlemen, esteemed jury, honorable mayor, dear Michael Krüger, dear Knut Elstermann—and dear family!

It means a great deal to me to receive this prize that is named for Thomas Mann, an author I love and greatly admire.

I have received congratulations from all sides, I am thrilled to see my name linked in this way to the name of this great writer, and of course I am also happy about the prize money, which is nothing to scoff at.

And even though my own affinity for Thomas Mann’s work is hardly enough on its own to justify this honor, I would like to make an attempt here to describe this affinity, and to address some points that connect me to Thomas Mann’s work.

When I was a teenager, I would ask my father every year if I could finally read The Magic Mountain, but every year my father would give me something else to read instead, something by Adalbert Stifter or Laurence Sterne, because The Magic Mountain still seemed to him like it might be “too difficult.” Eventually I got the impression that it must be a real magic mountain of some kind, too strenuous for a mere teenager to climb, or perhaps some sort of “open sesame” that would reveal its secrets only to a grown woman. When I finally did open the book, setting foot for the first time in the world of that reputedly serious, difficult magic mountain, I was initially taken aback.

The enchanting Madame Chauchat slammed the door with a crash, and I found myself captivated by her—and laughing as I read. Next I turned to Mann’s stories, discussing them passionately with my best friend at the time, considering all sorts of questions: whether my naturally blond hair and my healthy constitution made me better suited to the vulgar daytime world than to the wonderful nighttime world of a Gabriele Eckhof; to what extent a character defined by suffering and melancholy—ideally recognizable even from afar—was required if one hoped to create good and true art. But while these considerations troubled me, my worries were assuaged on every page, as Thomas Mann gazed from a judicious distance upon all the techniques that people use to regulate their interactions with others, training his great wisdom upon everything that takes place beneath those superficial vanities.

The question of literary role models is one that ultimately misses the mark, though we do recognize ourselves at times in the language of others.I made these first forays into Thomas Mann’s works before I began studying to be an opera director; in other words, before I discovered how Wagner’s universe is fragmented into a daytime and a nighttime world, before I anachronistically recognized Thomas Mann’s leitmotif technique in Wagner’s, before I yielded to the charms of Parsifal and Tristan myself—retroactively, as it were. Thomas Mann’s concern with the temporal structure of music continues to inform my thoughts—and my writing!—to this day; for instance, his question about the complex relationship between movement and stasis that “occupied” Adrian Leverkühn “more than anything else”: the “transformation of the intervals into a chord […], of the horizontal, that is, into the vertical, of the sequential into the simultaneous.”

The inevitable question of literary role models is a tedious one that ultimately misses the mark, but of course we do recognize ourselves at times in the language and thoughts of others, and in happy moments of reading we become aware of something that corresponds to us. And even if we forget certain details over the years—a given story line or character—while remembering others, the most important things sink in deeper than our memories, we incorporate them into our bodies, and they stay there, blind and mute, like our hearts, our kidneys, our bones, keeping us alive.

Between finishing Mann’s Magic Mountain and starting to read his Doctor Faustus, I lost the country I called home—the GDR. In the course of that time, I had internalized Mann’s reflections on all that is doomed to decline, his uncompromisingly accurate representations of illness and in-between states and all the things that occupy us when we are in those states. Hans Castorp lies on the chaise longue, professionally swaddled in blankets, increasingly resigned to his illness, while already his time is trickling away (but only we readers know that), running toward the First World War as if in a countdown, faster and faster. The slower life seems to become, the more quickly the moment approaches in which everything that had existed up to that point will be irreversibly lost on the battlefields.

Thomas Mann succeeds in inverting the order of farce and tragedy. One moment we’re enjoying a civilized lunch, then comes the mustard gas. And after the First World War comes the Treaty of Versailles, followed in short order by the food shortages in Europe, the inflation, the age of dictatorships: in Italy, in Yugoslavia, in Poland, in the Soviet Union, in Spain, and finally in Germany. Hitler is essentially a belated response to Versailles. After a few years of in-between time, Hitler answered one war with another, far surpassing the first by systematically murdering a portion of Germany’s own civilian population along with millions of people in other countries, even those who lived far from the front.

Anyone who could understand how an end becomes a beginning, how a beginning in its turn becomes an end again, would surely also understand that fundamental thing, the principle of transformation: how something unknown can emerge from what we thought we knew; how one thing can be swallowed up by another, very different thing—inverted, transformed into something monstrous, no longer controllable—or sometimes (just as surprising, though significantly more pleasant), into beauty, new life, new form. Anyone who understood that in all its depth could more easily cope with the hopes that come to nothing; or the loss of power, whether through political caprice, the actions of rivals, sickness, or the rise of the next generation; could more easily accept what is so difficult to accept: the deaths of those close to us—and our own deaths, which put an end to that thought process by which we seek to comprehend death until the moment when it finally catches up to us.

Even now we find ourselves in one of those in-between states. We know that the causes of the wars and crises in the Arab world, in Afghanistan, or in the Ukraine, can ultimately be traced back to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, which occurred a full 25 years ago. In many places, both within Europe and on its periphery, these developments are currently contributing to a radicalization that does not seem wholly unrelated to that of the 1920s. Orban is building fences that cut him off from European politics, while impatience is growing in other lands, not least in our own. A dictatorship has already been established in Turkey. Erdoğan’s approach is so similar to Hitler’s in 1933—which we can trace day by day in Thomas Mann’s diary—that the parallels are almost uncanny. In February 1933, Thomas Mann’s friends advised him not to return to Munich from Switzerland, where he was enjoying a winter vacation after a reading tour. After that, one thing led to another.

When his passport expired in April, the German authorities declined to renew it; his German bank accounts, his house in Munich, and his cars were confiscated, and with them half of his Nobel Prize was out the window; so in just a few weeks the most honorable Thomas Mann, practically a pillar of the state, was transformed into a refugee who did not know where to go. He wrote: “It is hard for me to bear the uncertainty of the future, this improvised life, the absence of any firm foundations that would, at least subjectively, remain valid forever, unto death. That is exactly what I have lost, and it is surely no surprise that a replacement cannot be found in the blink of an eye. […] Will I come to a miserable end?” He also wrote: “Very anxious, depressed, dreary mood. Must acknowledge that fundamentally there is no getting used to the loss of one’s home and of a stable livelihood.” As he would later learn, records had been kept of his public statements since 1925. In that in-between period, in the shadows, as it were, something was growing that would suddenly emerge and throw his life off-course from one day to the next.

A sentence from Mario and the Magician, which I read as a young girl, has stayed in my memory all these years. It goes: “It is likely that not willing is not a practicable state of mind; not to want to do something may be in the long run a mental content impossible to subsist on. Between not willing a certain thing and not willing at all—in other words, yielding to another person’s will—there may lie too small a space for the idea of freedom to squeeze into.”

When it comes to willing—or the formulation of a wish to will, if you will—dictators have an advantage over democratic countries. In Europe, we can agree on what we don’t want, at least not here in our own countries: war, poverty, torture. But what we do want is a question that requires more consideration. The very big, but also very capacious word “freedom” is not enough. First of all, because we have to ask: whose freedom? and at whose expense? Second of all, because it means taking a step back from willing as such, taking back our own wishes, when in doubt, in the interest of equality.

At this point, the freedom to which we so often appeal contains within itself the seeds of its own destruction. “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently,” said the brilliant Rosa Luxemburg, and there’s the rub, if we’re honest. Consumption is a constant process that offers the soul no satisfaction in the long run. Consumption is also a predatory process, a matter of life and death for people elsewhere. Taken together, these two facts mean that things can’t stay as they are. We are in an in-between state, and it will be important to understand what is growing there and where we are heading, where we want to be heading, before we are robbed of the ability to want anything at all.

All of these considerations confront us with the very central question of borders. Not only the borders between one country and another, or between one continent and another, but above all the borders within ourselves. Between ourselves as egoistic individuals and ourselves as members of a community in which we depend on one another, a community which, in light of the economic and ecological interdependence of all continents in our present era, can only reasonably be considered as a global community. Our own desires, too, sometimes transgress against the agreed-upon order or the law, posing the question: are we criminals? Or do we have to insist on these desires, in the interest of further progress? Such laws may ultimately prove inappropriate, they may have become inappropriate, or they may rest on a misunderstanding, like the marriage between Isolde and Mark.

Often enough, laws are purely arbitrary, the laws themselves are criminal. Do we lose ourselves, or do we save ourselves precisely by respecting the border, by insisting on it? So: is a border a constraint or a support? Of course it is always both, to a certain extent … But there is no law to absolve us of judging for ourselves. At that point, we are always on our own again.

Thomas Mann’s humor and his uncompromising portrayals would have been unthinkable if he had not already looked upon his own society from a tremendous distance, even long before he was expelled from it in 1933. It was his job, so to speak, to know what it means to be “outside.” That is at the root of Adrian Leverkühn’s entire bargain: the price that he pays for his art is that even in moments of happiness, reflection makes him a stranger. And, on the other hand, there is the power of feeling, the uncompromising will, the ruthlessness with respect to both himself and others. To be a drifter, an outcast, a third rail in a no-man’s-land, in an inhospitable territory, always engaged in an intimate dialog with borders.

What courage it took to have Aschenbach whisper his profession of love for the young boy shortly before his death in Venice, to have him confess the feeling that should not have been there, but was there nonetheless. Aschenbach is alone in his room when he makes this confession, but Thomas Mann was revealing himself to the thousands of readers he already had at the time, not least of all to his wife Katia. Isolde commits adultery. Aschenbach’s pederastic desire remains unfulfilled. But feeling and desire lead both characters to cross a border. And feeling and desire are, after all, the signs that someone is alive. Never more alive than in the face of death.

September 2016

__________________________________

Excerpted from Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces by Jenny Erpenbeck. Copyright © 2020. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, New Directions Books.

Previous Article

Natasha Trethewey on Surviving the White Mind of the SouthNext Article

When Hunter S. ThompsonRan for Sheriff