Will Humanity Ever Fully Include the Nonhuman World in Its Moral Circle?

Jeff Sebo on Our Attempts to Measure Intrinsic Value

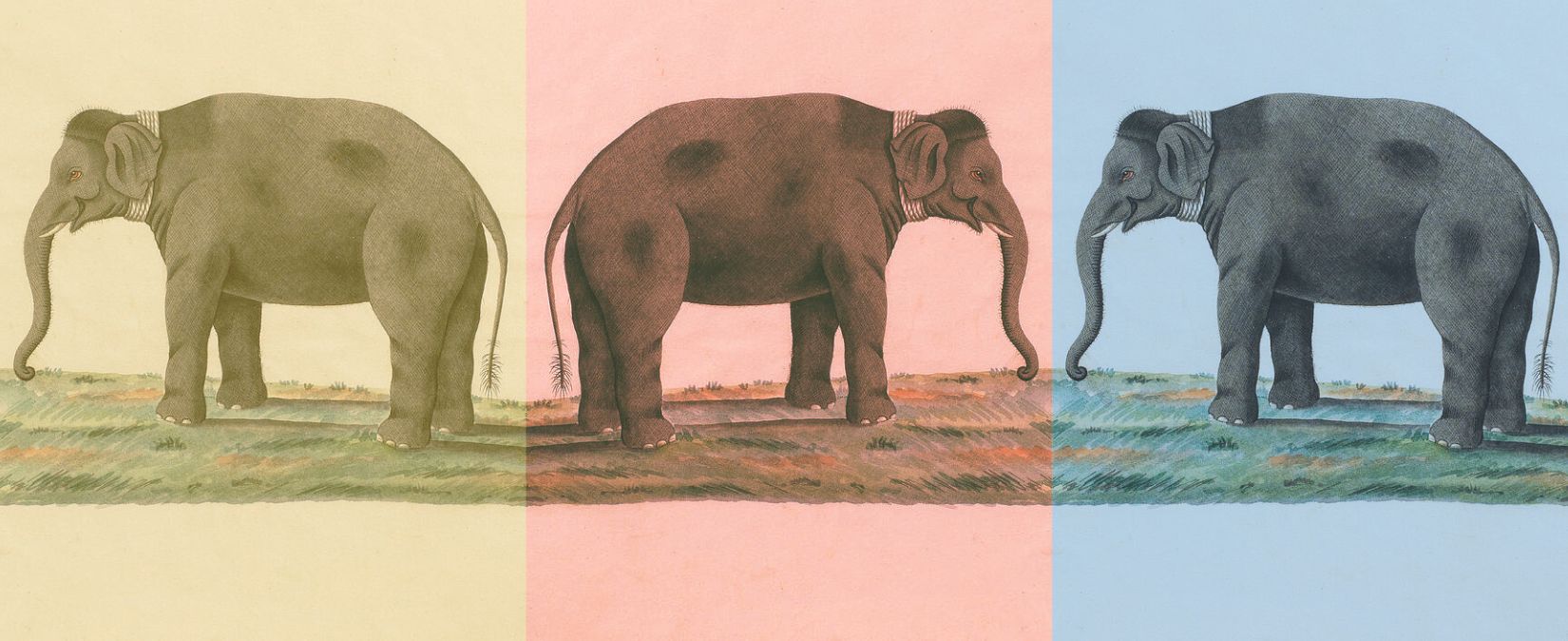

You run an animal rescue center, and you support a wide range of animals. But there are always more animals in need than you have the capacity to support, and unfortunately today is no exception. You arrive at work to find both an elephant and an ant with life-threatening injuries. You can treat one or the other but not both, and they require the same amount of time and money to treat. The only possible basis for making a decision is: Which animal has more to lose if they die? Are the stakes equal for both animals, or are they higher for, say, the elephant than for the ant?

As you ponder this decision, your team enters your office with an update. There are now ten elephants and ten million ants with life-threatening injuries. Fortunately, due to your innovative rehabilitation techniques, you have the power to treat either all ten elephants or all ten million ants at the same time.

But the situation is otherwise the same, and so the only possible basis for making a decision is, once again: Which animals have more to lose if they die? Even if the stakes are higher for a single elephant than for a single ant, is it possible that the stakes are higher for ten million ants than for ten elephants?

Since all moral theories have seemingly implausible implications, we need to compare moral theories holistically before we can select one.

As you ponder this decision, your team enters your office with a final update. There are now twenty elephants and twenty million ants, half of whom are made out of carbon and half of whom are made out of silicon. You can treat either the carbon-based elephants or the carbon-based ants or the silicon-based elephants or the silicon-based ants, but no more than that. The situation is otherwise the same, and so the question is, once again: Which animals have more to lose if they die? Do silicon-based animals have a stake in their lives at all, and if so, how do the stakes for carbon-based animals and silicon-based animals compare?

These questions are about the moral weight of lives. Do some moral patients have more at stake in life than others, and do some lives carry more weight than others as a result? Note that this question concerns only the intrinsic value of a life for its subject. We might also need to consider many other factors when deciding how to treat someone, such as: What kind of relationship do we have with them? What would it take for us to help them? And what would happen as a result of our helping them? We can consider these factors in the next chapter. For now, we can focus on the intrinsic value of a life for its subject.

In his influential book Animal Liberation, Peter Singer argued for the principle of equal consideration of interests. According to this principle, all equal interests merit equal consideration, no matter whose interests they happen to be. If you have the capacity for welfare, then you also have interests regarding your welfare; for example, if you can experience happiness and suffering, then you have an interest in feeling happiness and avoiding suffering. And when two interests are equally strong, they have equal intrinsic value, even if one of them resides in, say, an elephant and the other resides in, say, an ant.

However, Singer also noted that equal consideration of interests is compatible with differential treatment. For example, it might be that both the elephant and the ant have an interest in avoiding suffering, but that the elephant has a stronger interest in avoiding suffering, because the elephant is capable of experiencing more intense suffering for longer periods of time. If so, then it might be that the elephant has more at stake in life than the ant—not because an interest matters more when it resides in an elephant (that would be speciesist!), but rather because the elephant has stronger interests than the ant.

Should we accept that some moral patients have more at stake in life than others in this way? According to the equal weight view, the answer is no. We might feel tempted to say that the best possible elephant life is better than the best possible ant life, but that would be a mistake. Each species has a distinct form of life, and each life can be assessed only by species-specific standards. Thus, the best possible elephant life might be better for the elephant than the best possible ant life, and the best possible ant life might be better for the ant than the best possible elephant life. But neither kind of life is better as a general matter.

In contrast, according to the unequal weight view, some moral patients really do have more at stake in life than others. For example, since the elephant has a more complex brain than the ant, they can experience more happiness, suffering, and other such states at any given time. Since the elephant has a longer lifespan than the ant, they can also experience more happiness, suffering, and other such states over time. And since the elephant has a higher capacity for happiness, suffering, and other such states than the ant, the best possible elephant life is, in fact, better than the best possible ant life.

While the unequal weight view might seem straightforward, a lot depends on the details. For example, how exactly are welfare capacities related to brain complexity? We might be tempted to think that if one animal has ten times as many neurons as another, then the first animal can experience ten times as much welfare at any given time. But even if our welfare capacities generally track our neuron counts, they might not do so in a straightforward way. For example, it might be that ten times as many neurons corresponds to five times as much welfare, twenty times as much welfare, or many other possibilities.

Similarly, how exactly is our welfare capacity related to our lifespan? We might be tempted to think that if one animal can live ten times as many years as another, then the first animal can experience ten times as much welfare over time. But that might be a mistake too. Some brains have faster “clock speeds” than others, which means that they can perform more basic operations in a given unit of time. Can brains with faster clock speeds experience more welfare in a given unit of time? If so, then it might be that our lifespan, like our neuron count, is at best an imperfect proxy for our welfare capacity.

For these and other reasons, the principle of equal consideration of interests is compatible with many views about how to compare the moral weight of lives. As your team debates whether to save an elephant or an ant, some of you might hold that the stakes are equal for the elephant and the ant, others might hold that the stakes are a bit higher for the elephant, and others might hold that the stakes are a lot higher for the elephant. But as long as you agree that equal interests merit equal consideration, nobody is discriminating against either animal on the basis of their species membership alone.

Matters become even more complex when your team needs to compare the stakes for entire populations. Consider a simple example involving only elephants: If you need to choose between treating an elephant with a migraine and treating an elephant with a minor headache, then you should clearly treat the elephant with the migraine, since they clearly have more at stake in this situation. But what if you need to choose between treating ten elephants with migraines and treating ten million elephants with minor headaches? Can a large number of small harms carry more weight than a small number of large ones overall?

Similarly, suppose you accept the unequal weight view, along with the idea that an elephant has a higher welfare capacity than an ant. In this case, you might accept that if you need to choose between saving an elephant and saving an ant, then you should save the elephant, since that will prevent more suffering at present and allow for more happiness in the future. But what if you need to choose between saving ten elephants and saving ten million ants? Even if a large animal carries more weight than a small animal, can a large number of small animals carry more weight than a small number of large ones overall?

According to the non-aggregation view, the intrinsic value of welfare is not combinable across individuals in this kind of way. If an individual migraine is worse than an individual minor headache, then an individual migraine is worse than any number of minor headaches. Similarly, if an individual elephant carries more weight than an individual ant, then an individual elephant carries more weight than any number of ants. This view implies that your team should take the elephants to have the most at stake in this situation no matter how many other, smaller animals are enduring other, lesser harms.

In contrast, according to the aggregation view, the intrinsic value of welfare is combinable across individuals in this kind of way. A sufficiently large number of minor headaches can be worse than a single migraine, even if we might not always know what that number is. Similarly, a sufficiently large number of ants can carry more weight than a single elephant, even if we might not always know what that number is. This view implies that your team should follow the math: Even if you empathize with the elephants more, you should allow for the possibility that the ants have more at stake overall.

In his influential book Reasons and Persons, Derek Parfit showed that both of these views can have seemingly implausible implications in some cases. For example, the non-aggregation view seems to imply that a future with ten billion happy humans is worse, overall, than a future with ten very happy humans. That seems implausible. However, the aggregation view seems to imply that a future with ten billion happy humans is worse, overall, than a future with ten sextillion barely happy humans—humans who do nothing but listen to Muzak and eat potatoes all day. That seems implausible too!

Parfit famously found this implication of aggregation—that a large number of humans listening to Muzak and eating potatoes all day could be better off, overall, than a small number of humans leading complex, varied lives—so implausible that he called it the repugnant conclusion. Many philosophers still use this name for this idea, and while I have issues with the name, I also love a good pun. So in honor of Parfit, when I discuss the idea that a large number of small beings (say, ants) can carry more weight overall than a small number of large beings (say, elephants), I will call this idea the rebugnant conclusion.

Should we, like Parfit, resist this conclusion? Without attempting to answer this question here, I will offer two notes of caution. First, ethics is a marathon, not a sprint. Since all moral theories have seemingly implausible implications, we need to compare moral theories holistically before we can select one. Second, the risk of human bias is pervasive. Since our perspectives are shaped at least partly by our personal interests, our inability to empathize with small animals, our inability to imagine large numbers, and other such factors, we need to take our moral intuitions with a grain of salt.

Unfortunately, these problems are all amplified when we attempt to make welfare comparisons across substrates, too. When your team is deciding which animals to save, you might be more confident that the carbon-based animals have interests than that the silicon-based animals do. But if you were to determine that the silicon-based animals do have interests, then you would need to do more than make welfare comparisons between the elephants and the ants. You would also need to make welfare comparisons between the carbon-based animals and their silicon-based counterparts.

But to the extent that these animals do have equally strong interests, you can be confident that their interests are equally intrinsically valuable.

Intersubstrate welfare comparisons are even harder than interspecies ones. As much as your team struggles to compare the carbon-based elephants and ants, at least you know that they have the same material substrate and evolutionary origin. To the extent that you can compare their welfare capacities at all, these commonalities are what allow you to do it. Yet with the carbon-based animals and their silicon-based counterparts, you lack these commonalities. How can you decide which animals to save when you have no way to compare how much they have at stake?

As with the debate about moral standing, I will not attempt to resolve these debates about moral weight here. Instead, I will simply assume that the principle of equal consideration of interests is very likely correct. When your team is deciding which animals to treat, you might not be sure which animals have interests or how strong their interests are. You might also need to consider other factors, such as your histories with these animals, your capacity to help them, and the effects of helping them. But to the extent that these animals do have equally strong interests, you can be confident that their interests are equally intrinsically valuable.

Meanwhile, I will remain neutral about whether large animals carry more weight than small ones, as well as about whether large numbers of small animals can carry more weight than small numbers of large ones. My goal in this book is to argue that many nonhumans belong in the moral circle and that humans might not always take priority. As we will see, we can defend these ideas no matter what we think about the moral weights of lives, since soon enough, we might share the world with much larger numbers of much smaller nonhumans and with much smaller numbers of much larger ones.

If the United Nations were to release a truly universal declaration of rights, what would this declaration be like? Would it extend rights to all sentient beings, all agents, all living beings, or a different category entirely? Also, would this declaration extend equal rights to all of these beings, or would it extend stronger rights to some of them (say, individual elephants) than to others (say, individual ants)? And either way, what would the implications be in a global community that includes large numbers of small beings and small numbers of large ones? Would the United Nations embrace the rebugnant conclusion or not?

It might seem pointless to ask these questions. When most authorities still resist the idea of rights for individual chimpanzees and elephants, what hope can there be for large numbers of insects or AI systems? We might reasonably wonder whether these beings are morally significant at all. And even if we set that issue aside, we might also reasonably wonder whether we have the knowledge, power, and political will necessary to achieve and sustain even minimal levels of support for such large and diverse populations, given our apparent inability or unwillingness to do so even for members of our own species.

However, the idea of nonhuman rights might not be as far-fetched as it appears. Many governments now recognize that many animals merit moral, legal, and political protection for their own sakes. For example, France, Quebec, Colombia, Mexico City, and other governments now recognize many animals as “sentient beings.” And the Constitutional Court of Ecuador, the Delhi High Court in India, the Islamabad High Court of Pakistan, and other legal authorities now recognize some animals as rights-holders. Perhaps these developments will pave the way for wider recognition of nonhuman rights in the future.

Before we continue, it helps to step back and take perspective. Two hundred years ago, many humans found the idea of universal human rights odd. Today, however, a higher percentage of humanity recognizes these exclusionary and hierarchical attitudes for what they are: tools of oppression, motivated by bad ethics and science, a desire for power and privilege, and a failure to imagine more inclusive and egalitarian societies. Two hundred years from now, will our successors view our attitudes about nonhumans the same way? And if the answer might be yes, then how should we start viewing these attitudes now?

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Moral Circle: Who Matters, What Matters, and Why by Jeff Sebo. Copyright © 2025 by Jeff Sebo. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Jeff Sebo

Jeff Sebo is associate professor of environmental studies; affiliated professor of bioethics, medical ethics, philosophy, and law; director of the Center for Environmental and Animal protection; director of the Center for Mind, Ethics, and Policy; and codirector of the Wild Animal Welfare Program at New York University. He lives in Manhattan.