Wife, Mother, Labor Organizer: On the Hidden Activist Life of Betty Friedan

Haley Mlotek Explores the Tension Between the Political and the Personal For the Author of “The Feminine Mystique”

The Feminine Mystique was published by Betty Friedan in 1963. Reading Mystique now is an odd, contradictory experience—the silhouette of its influence on what is known as second-wave feminism is very present. Today, it reads as simplistic in its ultimate goals and immensely flawed in its execution. Much like any historical document, it’s clear that you had to be there to get it. But what Friedan did accomplish was a work that encapsulated an era as it changed. This is the thing about books: readers change, but pages don’t.

Friedan had been writing for women’s magazines for years, and she used their house tone to argue her points, the structure of a feature print magazine story to lay out the ideas that were not necessarily her own but would become synonymous with her name. Coontz has also written a biography of the impact the book had on the first generation to discover it, and it is a generous reading of the aura that still surrounds The Feminine Mystique, one that prizes the feeling the book inspired as much as the text itself.

Friedan may “evoke the kind of emotional response we now associate with chick flicks or confessional interviews on daytime talk shows,” Coontz writes, but she also “took ideas and arguments that until then had been confined mainly to intellectual and political circles and she couched them in the language of the women’s magazines she had begun writing for in the 1950s.”

For many years, Friedan told the same story: that she had led a life observing the contradictions between what she wanted and what was possible.

Like with many single works that come to stand in for social revolutions, the impact of Mystique was often exaggerated, and there was never a singular or unanimous response. Some sociologists at the time were more cautious, like Robert Nisbet, who in 1953 said that marriage contained way more “psychological and symbolic functions” than any family unit could possibly provide; the same year, Mirra Komarovsky spoke out against the potentially destructive impact that the ideal image of an American wife could have on ordinary women. Only three years later, in 1956, McCall’s published an article called “The Mother Who Ran Away,” establishing a new height for their circulation. When Redbook’s editors solicited their readers to answer the question of “Why Young Mothers Feel Trapped,” they got twenty-four thousand replies.

Yet when McCall’s published an excerpt of Mystique in one issue, 87 percent of all the letters sent to the magazine in response were critical of Friedan’s opinions. And the assumed radical nature of the book, too, was largely hyperbolic—at no point does Friedan urge middle-class white women to abandon their homes, husbands, children, or heterosexuality. She does not dare to explore new ways of building families and relationships. The final chapter, Coontz notes, even sounds a lot like what today’s conservatives recommend to women: part-time work, continuing education, volunteer roles in the community.

Most important, The Feminine Mystique never suggests that women could organize for better conditions in the home; never calls for deliberate, substantive changes in domestic or legislative spheres; and despite the communion it inspired in its readers, Mystique is, at its core, a self-help book encouraging women to act as individuals to improve their chances at a happy life by becoming a happy wife.

For many years, Friedan told the same story: that she had led a life observing the contradictions between what she wanted and what was possible, and that she began writing The Feminine Mystique because of the years she had spent wondering what was wrong with her that she, in her words, didn’t “have an orgasm waxing the kitchen floor.” (This was Friedan’s favorite rhetorical device, it seems, and one she used often. During a television appearance, she once told a host during the commercial break that if she wasn’t allowed more time to speak she would start chanting “orgasm” until she got to make her point).

But before she was a face of and a symbol for one kind of middle-class feminist reckoning, she was employed at the United Electrical Workers union, where she kept very, very busy. Coontz lists Friedan’s activities as including editing the community newsletter, assisting with the babysitting co‑op, and working as an organizer for a 1952 rent strike. Her early writings championed the experiences of workers, and the first few drafts of The Feminine Mystique apparently included shows of solidarity for the ways Black, Jewish, and immigrant workers experienced their own forms of oppression. The published version, which Coontz justifiably refers to as watered down, still has a few offhand references to Friedan’s connection to the civil rights and labor movements.

She writes that perhaps it was easier for her to start a women’s movement that changed society than it was for her to change her own life.

Daniel Horowitz, who has studied Friedan’s political affiliations, believes that her feminism is, at its core, part of her left-wing politics. But publishing Mystique as a mainstream work in the 1960s was not anything like publishing a workers’ newsletter coming out of the 1930s and 1940s. Even if she couldn’t have known what a blockbuster her book would become, she did want it to reach as many people as possible, and that meant avoiding being blacklisted, no matter the cost.

The Red Scare came for all manner of people, and no one was completely safe. Rebecca L. Davis pointed out in her book More Perfect Unions that just a few decades earlier, in the 1920s, when America was considering federal divorce laws, the comparison between that and the “easy divorce” available in Russia made lawmakers consider a simpler process as “equivalent to atheistic communism.”

In the early 1950s even the avowedly left-wing magazine The Nation felt compelled to qualify, when writing about the release of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (to which Friedan owed a tremendous but barely acknowledged debt; Friedan reportedly considered de Beauvoir disappointing), that the book had “certain political leanings.” Friedan’s own paranoia meant that she refused to credit her secretary, Pat Aleskovsky, for the work she did on Friedan’s manuscript because Aleskovsky’s husband had been publicly suspected of being a communist; Horowitz’s research itself has since been used to suggest that feminism in America was all part of a “communist plot.”

In the epilogue of Mystique’s ten-year anniversary edition, Friedan looks at her present rather than back or forward. “I’ve moved high into an airy, magic New York tower, with open sky and river and bridges to the future all around,” she writes. On the weekends, she would invite her friends who were divorced, unmarried, or otherwise a part of this family of choice, people who believed marriages could be made into something new.

And then there is a rare admission: she writes that perhaps it was easier for her to start a women’s movement that changed society than it was for her to change her own life. Still, she can claim accomplishments in both. Friedan says she used to be terrified of flying, but after The Feminine Mystique was published, she stopped being afraid. “Now I fly on jets across the ocean and on one-engine air taxis in the hills of West Virginia. I guess that, existentially, once you start really living your life, and doing your work, and loving, you are not afraid to die.”

Coontz remembers her own mother in Marriage, a History, as well as in A Strange Stirring, her history of the impact The Feminine Mystique had on its readers. Her mother was an activist who worked to free the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s and worked in the shipyards during the 1940s, but when the 1950s came she dedicated herself to homemaking. In the first few years after World War II ended, when more people had disposable income, food spending went up 33 percent, clothing by 20 percent, and household goods and appliances by 240 percent. Marriage offered a tangible material benefit (even if purchased on credit) that really could improve if not people’s lives, then at least their cooking.

__________________________________

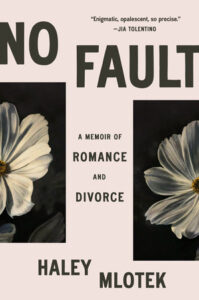

From No Fault: A Memoir of Romance and Divorce by Haley Mlotek. Published by Viking, a division of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Haley Mlotek.

Haley Mlotek

Haley Mlotek is a writer, editor, and organizer. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Nation, Bookforum, The Paris Review, Columbia Journalism Review, Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Hazlitt, and n+1, among others. She is a founding member of the Freelance Solidarity Project in the National Writers Union, teaches in the English and Journalism departments at Concordia University, and is the editorial lead at Feeld. Previously, Mlotek was the deputy editor of SSENSE, the style editor of MTV News, the editor of The Hairpin, and the publisher of WORN Fashion Journal.