I arrived at Zion National Park just as a shipment of porta potties was being delivered.

“They are new for this year,” Superintendent Jeff Bradybaugh said of the row of toilets, which were being set up in a parking lot near a popular trailhead. “It’s kind of a test. We’re going to measure each time those doors open and close. Each time they’re pumped out, we’ll have a volume measurement.”

“Wow. That’s a . . . fun job,” I said, grimacing.

“Yeah . . . That’s one we like to contract out.”

Hiring a private company to measure the amount of visitor crap was just one of several projects Zion was undertaking that summer. The park was tracking wait times at the entrance stations, surveying random hikers on popular trails, and holding “listening sessions” in the adjacent town of Springdale, Utah. The data collected would hopefully help Zion finally come up with a solution to a problem that had been plaguing it for years: The park was being loved to death.

When I first visited Zion in 1995, as part of a ten-day trip out west with my family, Zion “only” got 2.4 million visitors a year. I’m sure I was one of the most enthusiastic ones. I was fourteen years old, and I was having the time of my life.

Until that trip, the farthest west I had ever been was Kentucky. It was the first time I’d ever traveled on an airplane. When we landed in Phoenix, it felt like I had arrived in a whole other world.

“Holy crap,” I said. “That looks like Coachella.”My siblings and I had each been given our own Kodak FunSaver disposable camera. Rationing my twenty-four exposures for the week was even harder than making my Halloween candy last. I wanted to photograph everything. I wonder if that’s why the memories of that trip are still so vivid for me—at each stop, I had to carefully consider what amazing view I wanted to remember forever.

My family first drove our rental van north to the Grand Canyon, then started to make our way to California through Utah and Nevada, stopping for a night each at Zion and Bryce Canyon.

I had purchased a special journal adorned with an M. C. Escher print to serve as my diary for the trip, but I ended up having so much fun that I only filled a few pages. Looking back now on what I did write, there are several references to the crowds. At each park we visited, I commented on how the hotels and restaurants were booked solid. I remember it feeling stressful back then, but it was nothing compared with what the parks are like today.

In 2010, fifteen years after my first trip to Zion, visitation had only increased from 2.4 million to just under 2.7 million. But five years after that, it skyrocketed. In 2015, more than 3.6 million visitors showed up at Zion. By 2016, the number had climbed to nearly 4.3 million. Think about that. In the space of just a year’s time, an extra 646,281 people showed up. Over half of the national parks don’t see that many people total in a year.

“The word is out,” Bradybaugh told me. “Zion is a beautiful place.”

The word got out largely thanks to Utah’s Mighty 5 campaign. Launched in 2013, the series of scenery-soaked advertisements promoted the state by promoting its five national parks—Arches, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion—as a bucket- list-worthy itinerary, something akin to the Seven Wonders of the World.

“Five iconic parks, one epic experience,” the voiceover in the commercial said.

That’s exactly what Jennifer Lam and her friends were hoping for when I met them on the Emerald Pools Trail at Zion. They had flown all the way from Hawaii to tackle the Mighty 5 in just six days. Their itinerary was insanely ambitious, and also included stops in popular spots like Horseshoe Bend and Antelope Canyon, but the Mighty 5 were the mightiest draw.

“I kept seeing them mentioned on a bunch of travel blogs,” Jennifer said. “I wanted to come see them in person.”

In 2016, visitors spent a record $8.54 billion in Utah, translating into more than a billion dollars of tax revenue. The Mighty 5 ads aired everywhere from Germany to China. From a financial standpoint, the campaign was a tremendous success.

But for the parks, the massive increase in interest has not translated into a noticeable increase in federal funding. Year over year, park budgets have barely budged, despite dealing with nearly twice as many visitors. The entrance fees that all of the Utah parks charge at their gates don’t come anywhere close to what it actually costs to maintain and staff them.

Sometimes tourists aren’t even able to get into the gates. In 2015, in what The Times-Independent of Moab called an “unprecedented decision,” the Utah Highway Patrol shut down the entrance to Arches National Park for part of Memorial Day weekend. Traffic had backed up for miles and was creating safety issues for other motorists along U.S. Highway 191.

At Bryce Canyon, an hour-and-a-half drive away from Zion, the park website cautions road-tripping visitors that just one parking space exists for every four cars entering the park. Arrive early, they warn, or you might be circling all afternoon. Automobile traffic is banned altogether at Zion during peak season. Five years after my family drove through the park, Zion instituted a shuttle system to ferry visitors back and forth along the main road.

At first, the shuttles were a success, bringing peace and quiet back to the park. A fleet of fewer than twenty buses took the place of thousands of cars. But now even the buses have become overwhelmed. Today, instead of circling and circling to find a parking space, tourists might spend even longer waiting to catch a shuttle.

“At the visitor center, the wait can be forty-five minutes, even longer sometimes,” Bradybaugh said. “And there might also have been that long of a wait at the entrance station.”

“So before someone even sets foot on a trail, they’ve been waiting an hour and a half?” I asked.

“Yeah, it’s not the ideal experience, for sure,” Bradybaugh said. “And we want people to have that exemplary Zion experience.”

But what even constitutes an “exemplary” experience in a national park? To find out, Bradybaugh suggested I visit an office park on the outskirts of Denver.

The Denver Service Center does not offer official tours, although I wish it did. For anyone interested in the Park Service, I’d argue that a visit to that nondescript office provides a more illuminating look into how the parks actually operate than a trip to Teddy Roosevelt’s old cabin in North Dakota.

Situated among the strip malls of Lakewood, Colorado, the red- brick-and-glass building looks like it might be the headquarters of an SAT prep company or an e-commerce site that sells scented candles. The windows offer views of an Advance Auto Parts store and a Sonic Drive-In across the street.

But inside, a staff of more than two hundred employees shapes how Americans spend time in some of the most scenic spots in the country. When I visited, I did not see a single ranger in uniform, but instead found cubicle after cubicle filled with social scientists, landscape architects, cultural resource managers, contracting experts, and transportation specialists. These were the people behind the parks, focused on all manner of operational and ecological concerns across the Park Service.

Inside a conference room that looked straight out of Dunder Mifflin, I met with Kerri Cahill, an expert in visitor use management.

“It’s about making the experience as high-quality as it can be,” Cahill told me. “Typically, if you ask people, overall, did they have a good experience, they’re largely going to say yes, because they got to see the Grand Canyon or Yosemite or Yellowstone or these gorgeous, beautiful, iconic places. But when you dig a little deeper, you might find out that there were things that could’ve been better.”

Any ordinary company would be thrilled to have the customer satisfaction rates that a place like Bryce Canyon or Arches has. But as much as the Denver Service Center might look like a business from the outside, it does not run like a business inside. “Good enough” can’t be good enough for the Park Service, where the mission goes far beyond just getting bodies in the door. Cahill and her team are most concerned with the intangibles. For them, it’s more than just giving people the chance to see the Grand Canyon—it’s giving them the chance to be inspired by it.

Ensuring those inspirational moments survive an influx of visitors is no easy task. Take the shuttles at Zion. Within the park, they have successfully reduced noise and cut air pollution. Everyone agrees that’s been a good thing. But they’ve also created intense bursts of visitors arriving at popular trailheads all at once, which has created a new problem: Instead of people starting out on a hike one or two small groups at a time, now a group of fifty or so all unload simultaneously. There’s nothing inspirational about a mass of shuffling, shoving people.

At some point, with enough people, crowded parks don’t just become unpleasant, they become unsafe.At Zion, Bradybaugh had shown me a picture taken in a section of Zion Canyon known as the Narrows. The water there is only knee-deep, so it’s possible to walk for miles straight up the middle of the river—it’s one of my favorite hikes of all time.

But I barely recognized the Narrows in Bradybaugh’s photo. It was packed with people. A mass of hikers in tank tops and sun hats seemed to fill every available inch of the riverbed.

“Holy crap,” I said. “That looks like Coachella.”

It was crowded and chaotic and gross. Nothing about the picture looked like the tranquil, beautiful hike I remembered.

“Was that like, one particularly terrible day?” I asked hopefully.

“There are a lot of days like that now,” Bradybaugh said, shaking his head.

The people in that photo looked like they could have just as easily been at Six Flags Hurricane Harbor. Is that what national parks are destined to become?

The Organic Act of 1916, which established the Park Service, specified that parks must be preserved “in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” In other words, we are not just sharing the parks with millions of visitors each year, we are sharing them with the billions of people who have yet to be born. Thus far, preservation has mostly been thought of in terms of keeping the parks wild. Don’t chop down all the trees, don’t pave over every available space, et cetera. Let the parks be sanctuaries where people can enjoy unspoiled nature.

But the mere act of enjoying that nature can spoil it. Bradybaugh told me Zion had well over twice as many miles of “social trails” as it had official trails. Never as well planned or resource- conscious as the trails planned by the park, social trails are created when hikers, frustrated with crowds on the main path, find their own way. Unfortunately, in the process, they trample vegetation and damage the fragile soil. Bryce Canyon, a park created by erosion over millions of years, is very vulnerable to the type of erosion caused by a summer of people walking where they shouldn’t.

At some point, with enough people, crowded parks don’t just become unpleasant, they become unsafe. The most famous trail at Zion is Angels Landing, a steep climb full of switchbacks that eventually leads to one of the best views in the park. The last half mile is the tricky part. Hikers must scramble up a narrow cliff, holding on to chains nailed into the rock for support. At least nine people have slipped and fallen to their death since 2004.

In 1995, on my first visit to the park, my dad wouldn’t let my siblings and me climb the final bit. I remember being so upset with him, telling him he was being overly cautious. We argued as other hikers, some with even younger kids, passed us by.

“This will be my only chance, Dad,” I pleaded. “Pleeeease. I’ll probably never be back here again.” He held firm, and I sulked on my way back down the trail.

Two decades later, after I finally did the hike on my own, I called him to apologize.

“You were so right,” I said that night. “There’s no way we should have gone to the top as kids. That was crazy. I probably shouldn’t have gone now.”

The day I finally hiked Angels Landing, the narrow trail was teeming with hundreds of other visitors—tour groups wearing flip-flops and twentysomethings paying more attention to their GoPro shots than to their foot positioning. On a mountain where there’s already so little room for error, there was barely enough room to stand—one misstep by anyone could have inadvertently sent an entire group off the edge. The view at the end of the trail was spectacular, but I think there’s just too many people today for it to be worth the risk.

So what’s the Park Service to do? A quick and easy way to ease overcrowding would be to raise prices. That’s what any business would do. Charging more—maybe a lot more—would help pay for infrastructure improvements and would finally uncover what the “market rate” is for an exemplary national park experience.

When I talked to Superintendent Bradybaugh, Zion was charging thirty dollars per car for a one-week entry pass. The rate has now increased to thirty-five dollars per car. It very nearly went up to seventy. In 2017, then interior secretary Ryan Zinke proposed a significant price hike at the most popular parks like Zion, Yellowstone, and Yosemite, but the plan ended up being so widely criticized that he had to back off and settle for a more modest increase. Over one hundred thousand public comments, most of them negative, poured into the NPS website. People worried that if parks got more expensive, then the Americans who could least afford them would no longer visit.

“These parks belong to the people,” Bradybaugh had told me back at Zion. “We want to be careful that we aren’t pricing out certain folks.”

The vast majority of park units don’t charge entrance fees at all. For those that do, an eighty-dollar annual pass provides unlimited entry into every park in the country for an entire year. (By comparison, one day at Disney’s parks costs well over one hundred dollars.) The national parks are a good deal by design.

In Denver, Kerri Cahill told me that establishing timed entry reservations was one of the options under consideration at popular parks like Zion. Show up without one, and you won’t be let through the gate. It’s a strategy that’s worked well for museums. The Getty Villa in Malibu is free to enter, but visitors must first reserve a specific time and date online.

Somehow, though, being told when we can and can’t go to our parks just feels . . . wrong. “The mountains are calling and I must go,” John Muir wrote. Not “the mountains are calling and I must go next Thursday at 3 P.m., because that’s the only ticket I could snag that was available.”

And yet several parks already have reservation systems in place for backcountry permits and tours and popular campgrounds. It’s hard to imagine a future in which some kind of reservation system doesn’t continue to spread across the more popular parks. Especially if the goal is to preserve some of that intangible inspiration. What’s better, ten thousand people a day all having a miserable time? Or seven thousand people a day all having a fantastic one?

I don’t want to paint too gloomy a picture. In the overall scheme of things, the story of overcrowded parks is really only the story of certain parks. The Park Service manages more than four hundred units, but over half of all visitation occurs at less than thirty of them. Even with the Mighty 5, it’s really more like the Giant 3, with Utah’s Canyonlands and Capitol Reef still not quite bursting at the seams. In a year in which Yosemite saw five million visitors, a park like Pinnacles, less than two hundred miles away, received closer to two hundred thousand. There’s still plenty of room to roam out there.

Even at the most popular parks, I was shocked by how the crowds would disappear the moment I wandered away from the parking lots. The vast majority of visitors spend mere hours at the parks. They don’t have time to take long hikes in between driving to lookouts, snapping photos, and visiting the gift shop.

“The national park system must be temporarily reduced to a size for which Congress is willing to pay.”Utah’s license plate features a picture of Delicate Arch, which makes a strong case for it as the mightiest attraction in all of the Mighty 5. While it’s definitely worth seeing, there are more than two thousand other arches at Arches National Park. My four-and-a-half-mile round-trip walk out to the far less crowded Double O Arch was one of the best hikes I did all year. Wake up a bit earlier, walk a bit farther, and you can still have the views to yourself.

Also, none of these overcrowding concerns are particularly new. In 1869, when David Folsom—part of the first official expedition to explore the Yellowstone region—saw its largest body of water, he wrote, “We felt glad to have looked upon it before its primeval solitude should be broken by the crowds of pleasure seekers which at no distant day will throng its shores.”

In 1953, back when the national parks received less than a tenth of their current visitation, essayist Bernard DeVoto published a piece in Harper’s Magazine titled “Let’s Close the National Parks.” Alarmed by the poor conditions he’d observed at parks where “there are not enough rangers to protect either the scenic areas from the depredations of tourists or the tourists from the consequences of their own carelessness,” DeVoto suggested we shut them down altogether.

“The national park system must be temporarily reduced to a size for which Congress is willing to pay,” he wrote. If the Park Service, the “impoverished step child of Congress,” couldn’t be properly funded and staffed, DeVoto argued, then the parks should be “temporarily closed and sealed, held in trust for a more enlightened future.”

At Bryce Canyon, I got a preview of that future while being reminded of my past. As I walked through the parking lot at Inspiration Point, I saw a family with three kids who seemed to be around the same age as my brother, sister, and I were when we first visited Bryce. The kids were speed-walking around the rim carrying a Junior Ranger pamphlet, occasionally bending down to grab something off the concrete. I could tell from their excitement that they were on some sort of scavenger hunt.

At every park, the Junior Ranger program gives kids (or really, anyone who wants to participate) a certificate or a merit badge for completing a series of activities meant to connect them to the place. It’s generally stuff like “spot a prairie dog and a lizard,” “complete a word search of Native American words,” or “interview a volunteer about what they do at the park.”

As I got closer to the family at Bryce, I finally noticed what the kids were doing. They were picking up trash.

“Seven, eight . . .” the little girl crowed as she snatched up what looked like gum wrappers near a bench. To become a Junior Ranger at Bryce, one of the requirements is to “dispose of at least ten pieces of litter.”

Our best weapon for protecting the parks from people has always been people. Even if it were possible to somehow lock our national treasures away, preserving them for some “more enlightened future,” how would that enlightenment ever arrive unless people had a chance to experience these places for themselves? The more people who visit the parks; the more people who see, first- hand, what needs to be addressed; the more kids who are able to feel that same feeling of inspiration at Inspiration Point I felt when I was a kid, the more chance we stand of protecting the parks.

Perhaps the record-breaking popularity of the parks will help us love them back to life. In addition to significant staffing shortages, the Park Service currently has a massive twelve-billion-dollar maintenance backlog. With enough political pressure, Congress could take this on. Finding funding gets easier when there are 330 million visitors out there cheering you on.

Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, firmly believed that as many people needed to visit the parks as possible. To Mather, the parks represented our greatest source of national pride. They were places with a unique capacity to soothe our “national restlessness.” Once, when asked if he was concerned that more visitors meant more trash, he replied that “the parks belong to everyone.”

“We can pick up the cans,” he said. “It’s a cheap way to make better citizens.”

__________________________________

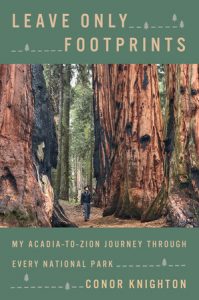

Excerpted from Leave Only Footprints by Conor Knighton. Copyright ©2020 by Conor Knighton. Excerpted by permission of Crown. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.