Why the Rise of Morally Gray Women In Fiction Is Good For All of Us

Megan Barnard on the Deliciously Unlikable Yet Complex Female Protagonist

One hot, languid summer, I became obsessed with morally gray characters. For me, it all started with Amy Dunne from Gone Girl. I’d never before read a book where the female main character was so deliciously unlikeable.

My favorite part of the book was the ending. Amy Dunne, who set her husband up for murder because of infidelity (and let’s be honest, generally being a dick) gets her own fairytale ending. She spent the book lying and manipulating—and actually ends up being the murderer after killing her ex-boyfriend. And what happens to Amy? Nothing. Nothing happens. She doesn’t go to jail. She doesn’t even lose her husband. She gets to have the life she wants, even for all her sins. Since Gone Girl, I’ve realized I love stories like this. Stories where the women at the heart of them aren’t just good or evil but are morally gray.

We’ve all seen the movie or read the book: a woman strategically plans to steal jewels from a museum. She’s out for money, revenge, or just fun. Then she goes home and makes dinner for her daughter. We learn she’s a single mother. We empathize with her struggle, with her boredom. After all, most of us have been there. Morally gray characters like her, like Amy Dunne, are having their day in the sun. And it’s a good thing for all of us.

Many of our ancient stories and myths put the characters at their heart in a specific box: good, or bad. There was no middle ground, no room for any other choices. A classic example of this is Lord of the Rings. While it’s a wonderful story in many ways, in terms of character, it’s lacking because they’re usually flat, two-dimensional. Aragorn is good: he makes no bad choices and has no bad impulses. Similarly, the Orcs are evil; bloodthirsty and violent, they have no good impulses, no kindness within them.

We’ve made these distinctions for centuries, not just for fictional characters, but for historical figures as well. However, when we look deeper into these characterizations, we see that depictions are often gendered. Richard I is brave and strategic (even though he led crusades that brutally murdered thousands of Muslims); he is called “the Lionheart”. Catherine De Medici, Queen of France, is a scheming witch, called “the Serpent Queen” (even though she was a loving mother and brilliant strategist).

We have seen a shift in our ability to like and root for morally gray characters in the past century or so: but only if they’re men. We cheer when Danny Ocean pulls off another heist (he’s brilliant, charismatic), and we’re thrilled when Sherlock Holmes solves another crime (his rude, antisocial behavior just adds to his charm). However, when women try to make similar choices (steal, lie, strategize, analyze), she’s often interpreted as pushy, aggressive, manipulative. She talks too loudly (and why is she wearing a pantsuit?) and who is watching her children?

It’s great that we’re beginning to look at both men’s and women’s choices in shades of gray instead of the good/bad binary.

While we often still have to struggle against this good/bad binary (especially when it comes to political and public female figures), we’ve lately begun to re-examine our views of “evil” women, giving them the chance to move from evil into the gray, where men have existed for so long.

We can see this in the popularity of many books that have morally gray women at the heart of the story. For example, Vaishnavi Patel’s wonderful novel Kaikeyi (an instant NYT Bestseller) brings to life the “evil stepmother” figure of Kaikeyi from the ancient story the Ramayana. In Kaikeyi, Patel turns Kaikeyi from a ghoulish figure into a wise and cunning woman who expands the power of women at her court, providing us context and understanding for her banishment of her stepson, Rama.

We see a similar reclamation of an “evil woman” in Circe (a #1 NYT Bestseller) by Madeline Miller—the retelling of the myth of the goddess and witch Circe from The Odyssey. In the original story, Circe turns men into pigs (for no particular reason other than she’s evil) until she’s outwitted by the brilliant Odysseus. In Miller’s story, Circe becomes a full-formed character who sometimes makes bad choices (turning a rival into a monster) but is also powerful and deeply caring (later killing the monster she created, saving thousands of lives).

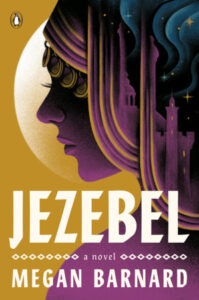

I thought a lot about women like this when I was writing my novel Jezebel—a feminist retelling of the reviled queen’s story—because Jezebel is nothing if not morally gray. She wants her family to be safe, but she also wants her name to be remembered. She kills to cultivate and consolidate power. Sometimes she kills because she is afraid or angry. She is fierce and smart and sometimes cruel. This is one reason we’ve hated Jezebel for so long—she’s a historical figure who took on the traditionally “male” role (with an associated consequence of eventually bringing ruin to Israel); when we look at her actions in the gendered view we’ve used for so long, we can only see her in a negative light.

Thankfully, I’m not the only one who loves these morally gray characters, A quick look at the #morallygraycharacters hashtag on TikTok has over 154 million views. Some of the best-selling books and TV shows of the last decade have portrayed morally gray women.

It’s great that we’re beginning to look at both men’s and women’s choices in shades of gray instead of the good/bad binary. Hopefully, this will increase our ability to view all people (fictional and nonfictional) with empathy and the understand that everyone contains multitudes. I think that’s one reason we’ve all liked the Barbie movie so much: we can understand why Ken wants to take over Barbieland, and why Barbie wants to leave it.

I hope that our new love for morally gray characters will continue. I hope we continue to reject a gendered binary of good/bad and instead look at each other (friends and neighbors, politicians, and public figures) as the morally gray, multifaceted people that all of us are.

__________________________________

Jezebel by Megan Barnard is available from Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Megan Barnard

Megan Barnard is a former literary agent and editor turned full-time writer. When she’s not writing, she drinks coffee, travels widely, and shuffles towering stacks of books around, so they don’t kill her or her husband. She lives in Maryland with her husband and her pup, Pippin.