Why Testimonial and Confessional Writing Remains Necessary in the Post-#MeToo Era

Jamie Hood In Defense of the Earnest, the Sentimental, and Those Who Still Need to Put Their Trauma Into Words

When #MeToo happened, everything women wrote about rape outside reportage was crowned by the same bloody image—Judith Beheading Holofernes—by the Italian baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi. You’d think all of us were running around planning to cut men’s heads off, but I’ll admit, back then, I sort of was. I wanted my rapists dead. I boiled over with viciousness. Nothing satisfied me like escalating conflicts with the men who’d started them, the ones who called me names or touched my body when I didn’t want it.

In bartending, it’s amazing how often a man thinks he can flick your tits or grab your ass while you struggle past him, arms full of other people’s dirty pint glasses. I worked in a lot of dives then. It’s worse in those, but at least you can tell someone to fuck off. My tongue became a blade, yes, but my body, too, burst with white heat. Everyone acts like you’re a crazy woman for speaking out about your debasement, but sometimes you have to play the Cassandra, sometimes even Troy must fall. I kept waiting for the opportunity to throw fists.

In southeast Virginia, most of the girls I grew up with knew how to fight. Earrings off, nails off, jewelry off. There were a lot of white girls named Krystal, a lot of heads getting slammed into a lot of lockers. If you were a trans girl where I came from, you needed grit to get by. Maybe it’s why I’ve never been much good with court intrigue. For most of my life, violence came in the form of a fist.

Casting traumatic testimony as politically inert or even ideologically regressive is the duty of the contrarian, the reactionary, the dictator. Such demobilizations transform nothing and no one.

With those men I never had the pleasure. But still, I told myself, what I’d failed at before—protecting myself from rape—wouldn’t happen again. I was in training for the next time. I would be no Laura Palmer. I was J.Lo in Enough. I was Ashley Judd in Double Jeopardy. I honed my body, angling my whole life toward reprisal. I couldn’t bear a closed space and never ate, but I was agile. My hunger left me edgy. Every part of me became a sharp point. My long hours at the bar gave me stamina, and what’s more, I got a lot of practice kicking bastards out of the places I worked. A few of the women I hung around with then had the same patch on their jackets: DEAD MEN CAN’T CATCALL. One gave me a pocketknife after I told her my shit. She showed me how to flick it silently open.

Once I started talking about the rapes, words tore through me. I became an oracle of my self, I wasn’t able to stop. Logorrhea is one name for this compulsion, a pathological need to divulge. At times the furious rhythm of my confessions felt like speaking in tongues. And my verbal irrepressibility was another rationale for the writing. I needed somewhere to stuff away all that speech. When I began to write, I arrived at a different condition: hypergraphia. Hundreds, probably thousands of pages over the years, amassed in three laptops, printouts scattered through old storage containers or folded inside favorite books on forgotten shelves.

By the time my little rape poems began getting published, I was told Judith Beheading Holofernes was cooked. Everyone had seen it by then and grown tired. As if it were possible to see that spurt of blood and not know freedom. I guess repetition can diminish the power of a thing for some people. What I loved best in the painting were Judith’s and Abra’s bored looks, like they were spraying Raid on a nest of roaches. With my fingers I traced photographs of Gentileschi’s other paintings—not just her interrogations of violence and spectacle (the multiple Judiths, Jael, Susanna, Danaë, Bathsheba), but the self-portraits also, her allegories of melancholy, ecstasy, penitence. The scholar Mary Garrard remarks that you can separate a Gentileschi from its imitators by the hands of her women, which are muscular, mobile, and purposeful.

Femininity in a Gentileschi is never passive. I read about the rape trial she withstood, the way her inquisitors bound her hands in thumbscrews during her time on the stand. She shouted “È vero, è vero, è vero!” (“It’s true, it’s true, it’s true!”) while testifying against her father’s acquaintance, Agostino Tassi, who’d defiled her with the assistance of another man, Cosimo Quorli, and Tuzia, a female friend of the Gentileschi household. Artemisia might never have painted again. At a time I nearly abandoned this project, I read Anna Banti’s novel of Artemisia, the original draft of which was destroyed after the Nazis detonated mines they’d planted along the Arno in occupied Florence. Susan Sontag dreamed of Banti stunned among the rubble, grieving the “death all around her [and] the manuscript that exists now only in her fragile memory.” I went on.

Then the man who’d coordinated my gang rape began haunting the neighborhood again. Probably he’d been in jail awhile: he was a drug dealer, small-time, but had circulated enough cocaine through the area to be known to the cops, and locked up a couple years, which was about how long it’d been since I’d seen him. This was my guess anyhow, as I knew where he lived with his mom—it was where the rape took place, a couple blocks from where I worked—and I couldn’t think where else he’d have gone. Now I’d pass him on the streets and his face tore through me like a nuclear blast. I’d be in a debilitating panic attack for days. Shell-shocked, I remember thinking, though of course I’d never been in war.

The rapes were on me: total immediacy. I found myself on all fours. One of my best friends then was an ex-con, a huge guy, and when I told him of these encounters he said he’d kill the man for me if I only asked him to. He had no issue going back in, he said. Prison didn’t frighten him anymore. I said homicide was a different beast than copping a drug charge, but he was a man of honor, a true gentleman. “Damaged” women like me tended to flock to him. His offer put things in starker terms.

My revenge found form, then. It was paint on an easel. Clay in my hands. I dreamed of John the Baptist’s oozing head on Salome’s silver plate. Judith returned to me, imperturbable, with her glittering sword. I pictured Jael and Sisera—the fatal tent peg; that supple temple. Now my bloodlust was not mere fantasy. Death was in my hands. The trouble was, I loved my friend and didn’t want him going anywhere. His family needed him free. I needed him here. First of all, he was the only man who’d ever protected me. He walked me home at the end of late bar shifts, and when he visited me during them, he played bodyguard. When men fucked with me, I didn’t have to be the Medusa, because he’d cool things off.

One night I eighty-sixed two guys who threatened to kill me while they walked out the door. An hour later they were back, three other men in tow. All five sat in a parked car just outside the entrance to the bar for hours. My friend waited through the long night with me. I felt sure nothing bad could happen with him around. But being protected by another person isn’t the same as living beyond fear, and at last I saw I couldn’t let anyone forfeit their life or liberty for mine, or for my “honor,” whatever the fuck that was. Besides, if someone was to kill my rapists, it ought to be me. The desire vanished. I saw what I really wanted was that no one else get hurt.

It was obvious as #MeToo unfolded that the movement was fallible—that to achieve mainstream recognition, it would leave a lot of people out. Nevertheless, its revelations exposed the immensity of the problem: sexual violence was everywhere, and all the time. This knowledge freed me from ego, I guess, and something I needed in that moment was to surrender centrality. Until I was able to look outside the fractured self, I would never refashion it. What a relief to find I wasn’t special. And how devastating.

It’s banal to say, but my sense that I was an aberration was what made me so sure I’d deserved all that had happened. Shame particularizes. Shame isolates. Now I no longer see my trauma as exceptional, which is a strange thing to confess at the beginning of a memoir about it. But if I am singular in some way, it’s not through my endurance of violence. I refuse that naming. Rape seems to me only a trouble I am writing about, a trouble I’ve been better at managing lately.

Where Tarana Burke’s 2006 vision for #MeToo prioritized procuring resources for low-income Black and brown girls who’d survived sexual trauma, 2017’s reboot was animated chiefly by storytelling. It rallied an ambient solidarity through supposed collective recognition, gathering force through an infinite chorus of voices bearing witness. Whose voices were amplified as the plot coalesced was another matter altogether. It seemed the stories that gained the most traction were the most glamorous, or else the most gruesome. That the movement’s narrative status quo mirrored the broader culture’s warrants thoughtful, rigorous critique, but it doesn’t discredit the watershed moment entirely.

In Dissent, Sarah Jaffe remarked that #MeToo’s orientation toward first-person narrative disproportionately invested energy in “naming and shaming” over material action. Hers was a useful rejoinder: no viral tweet will end rape. Nor will a memoir—not mine or anyone else’s. “Bearing witness” doesn’t produce liberation from thin air. Even still, casting traumatic testimony as politically inert or even ideologically regressive is the duty of the contrarian, the reactionary, the dictator. Such demobilizations transform nothing and no one. They aren’t worth our time.

That the #MeToo movement of 2017 became clarified in the confessional mode made it fertile ground for cultural critics, even if the backlash itself took more time to root in our sedate groves. The long pop-cultural tail of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, for example, wasn’t properly cut and cauterized by books media until nearly six years after its meteoric success. But once it coagulated, A Little Life came to be seen as the ur-text of what Parul Sehgal would name “the trauma plot” in a December 2021 issue of The New Yorker.

Some identified Yanagihara by name—Sehgal, Brandon Taylor, Andrea Long Chu, and Christian Lorentzen, who wrote an early pan of the novel for the London Review of Books (“What real person trapped in this novel wouldn’t become a drug addict?” What person indeed?). For others, her “agony novel” was the unacknowledged and invisible nucleus of a diseased literary organism that had rendered fiction psychologically cheap and narratologically flat. Trauma, in these readings, had become the tiresome explanatory bedrock beneath all contemporary writing.

As Sehgal argued, unlike the marriage plot, which opens the novel searchingly toward an unknowable future, the trauma plot is anchored only in the recursive muck of the past. For many, this plot was a uniquely modern marvel—the freeze-dried and vacuum-sealed by-product of a cultural market dominated by Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score, Lena Dunham’s Brooklyn autofiction Girls, reality TV, and a decade of personal essay verticals at digital pubs like Gawker, xoJane, Jezebel, and Thought Catalog. For Slate in 2015, Laura Bennett named this the era of the “first-person industrial complex,” classifying a parasitic dynamic between writers, editors, and audiences that (usefully) generated space “for underrepresented viewpoints” while consequently creating an ecosystem in which writers felt (to cite Jia Tolentino, quoted in Bennett’s piece) that the “best thing they have to offer is the worst thing that ever happened to them.”

Trauma plots are not above evaluation, and I respect the work of some of these critics quite deeply, but what troubles me in this increasingly consolidated recoil is its wholesale exile of authors from self-knowledge—the subterranean, insidious idea of our relation to writing as unexamined, crude, and lacking competence with self-reflexivity, humor, and play. Like there’s no reason to write about trauma except to make a buck. Like if you talk about having lived through something awful, that’s all you’ve ever talked about or ever will. Like you have no agency inside a story you yourself chose to tell. It’s an old trick, the same used to argue autobiography is antithetical to art; that confessional writing is without tradition; that it’s hack, just bloodletting on the helpless, virginal page.

It damns trauma as only ever individual, and so functionally apolitical, even when texts position trauma as inextricable from systemic injustice—indicting class exploitation, for example, the continuing historical aftershocks of the Atlantic slave trade, or rape as a tactic of war (really even: rape as a war against women in its own right). These stories are rendered dismissible as “identitarian” cudgels, weaponized against lone perpetrators and taken on to lay claim to a de facto moral authority that, apparently, attends bodily harm. Which is news to me.

Although it’s fiction, A Little Life understands it’s possible to spend most of a life reckoning with sexual trauma. I surely have.

What remains funny about many of these arguments is how they paint writers of trauma as inartful—dupes of the market—while at the same time calling us con artists and tricksters. We’re somehow too stupid to see we’re selling our souls to the god of publicity, even while we leverage our nightmares against a defenselessly porous reading public and cash out. The ethical crime of storytelling is handily shifted back onto the person recording their victimization: you are the vector of damage.

Trauma, in this frame, becomes a contaminating force. We infect others with our shameful sob stories, and what we take from those people is their time, their attention, and all the money in their pockets. The world over, readers can do nothing but go on buying and consuming our exhibitionist displays. We are succubi. We are Plath’s Lady Lazarus, unwrapping ourselves before the “peanut-crunching crowd” for little more than a Buffalo nickel.

I should say I think it’s perfectly fine to loathe A Little Life. For a while, I’d see those flimsy tote bags all over the New York City subway, the ones with

JUDE&

JB&

WILLEM&

MALCOLM.

stacked on taupe canvas. I’d think how odd to bear their names like a fashion brand on your body, and how terrible it would be to realize you were the Jude of your friend group—until I remembered I was the Jude of several of my friend groups. I have a soft spot for the novel. There’s something in its excess that rang true to me when I first read it. Although it’s fiction, A Little Life understands it’s possible to spend most of a life reckoning with sexual trauma. I surely have. One of the troubles with the dominant narrative of #MeToo was that it continued to imagine the experience of rape as an anomalous event in the usual order of a life, even as it underscored the overwhelming breadth of rape culture itself.

But for women without support networks or safety nets, without certain social privileges or legibilities, I suspect the repetition of this trauma is commoner. If you don’t have the money to get away from a partner who’s beating or raping you, you could spend years in it. Some of this I watched right up close. One disquisitional frame against A Little Life had to do with quantity: the amount of trauma Jude suffered was understood as inexorably unbelievable. But for me, it was one of the only novels I’d read that saw how pervasive intimate violence is in our lives, and how shadowy, how stigmatized, how great the pressure to stay stoic in facing it, to weather violence without complaint.

A Little Life worked for me, too, I guess, because I love a Gothic fairy tale, and I’ll always jump in the ring for the earnest, the cringe, the sentimental, the too much. I write for the messy bitches. I write for girls who haven’t given their grief language. In the era of the Hater, it’s no surprise to me that a dozen critics decided a book so many people were reading was undeserving of its audience and accolades. But to crucify a novel that never claimed to be Middlemarch for rank literary pretension seemed to me sort of strange.

What’s more, I found it thin how so many of these quarrels with “the” trauma plot seemed to be about A Little Life with maybe one or two other novels thrown in, which isn’t so much a canon trouble as it is a problem of three books some person with a byline didn’t like. Many critics I know are working writers, and most of us love books, are curious about art, and want conversations that expand the world rather than shrink it. Then some critics have too much damn time on their hands, so everything they read they read paranoid. Call it Terminal Op-Ed Brain. Call it a salaried position. They like the thrill of the takedown without the rigor of generosity, which sounds a little like what they accuse all us sellout trauma morons of, no?

__________________________________

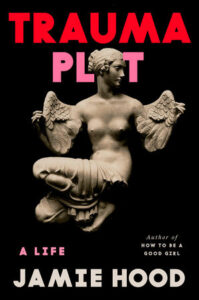

Excerpted from Trauma Plot: A Life by Jamie Hood. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Jamie Hood.

Audio excerpted with permission of Penguin Random House Audio from TRAUMA PLOT by Jamie Hood, excerpt read by the author. © Jamie Hood ℗ 2025 Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jamie Hood

Jamie Hood is the author of how to be a good girl, one of Vogue’s Best Books of 2020, and regards, marcel, a monthly newsletter on Proust and other miscellany. Her essays and criticism have appeared in The Baffler, Bookforum, The Nation, Los Angeles Review of Books, The New Inquiry, The Drift, and elsewhere. She lives in Brooklyn.