Why Television Can Be Our Best Writing Teacher

Christine Ma-Kellams on What She’s Learned From the Small Screen

There’s this famous interview I think about a lot—my Roman Empire—where a journalist asks Toni Morrison how she became such a great writer. I’m paraphrasing, but she says something to the effect of: the look my dad gave me every time I walked into the room—that’s why I’m the writer I am today.

I love Toni Morrison as much as the next person, but I had no idea what she was talking about. Luckily for the rest of us, a doting and highly expressive father must not a be a universal prerequisite for great writing. Sure, my dad was around, but we hail from a part of the world not known for their exceedingly readable facial expressions (so much so that there used to be entire stereotypes dedicated to just how “unscrutable” our ancestors were).

Also, he happened to be both an immigrant and a Ph.D., which meant that I was the kid who wore a housekey around my neck on a thread and let myself into most rooms at home, where the primary interaction I witnessed were those on our Magnavox TV. As a kid, television kept me company after school and gave me a reason to get up on Saturday mornings. As a grownup, it taught me everything I now know about character, dialogue and plot.

Good television can have as much artistic merit as any literary masterpiece.

Take The Office and The Sopranos. Together, Michael Scott and Tony Soprano offer a masterclass on crafting antiheroes. I spent most of the first season of both these shows puckering one orifice or another over some cringe-worthy or bloodily violent scene. By the end of a dozen episodes though, I found myself deeply, madly invested in (maybe even a little in love with) both Carrell and Gandolfini, even though neither were my type.

But as the saying goes, the opposite of love is not hate, but indifference. So give the audience a character to despise. Add in a single vulnerability—an endearing or slightly pathetic sense of FOMO, a tenderness towards feathered birds in swimming pools—and an antihero is born.

The Office does something else idiosyncratic: in making itself a show about a documentary, it periodically breaks the fourth wall. This doesn’t happen often, but its rarity only makes the occasions where it does occur more memorable—like when we all thought Pam and Jim, the show’s resident lovebirds, were going to do the unthinkable and stray, particularly when an attractive cameraman left his spot behind the lens to give her a broad shoulder to cry on.

Break the fourth wall enough and you may find yourself in a heap of drywall and rubble. Do it sparingly, though, and something much more interesting can happen. My favorite books also use this technique—Lauren Groff does it in Fates and Furies; Kevin Chong does it in The Double Life of Benson Yu. In my own novel, The Band, towards the very end, I make an offhand remark—hidden in a footnote—that blurs the lines between myself and the narrator when I reference my next book that’s a prequel to the current one.

As a postdoc, I heard about Breaking Bad during a lab meeting. I can no longer remember the neuroscientific findings of the guy who mentioned it, but I can’t forget Walter White if I tried. Vince Gilligan’s masterpiece is a lesson in plot and the art of cliffhangers. Years later, deep into writing my debut novel, I remembered the strategy of ending each chapter—like Gilligan did with virtually every episode—with an event or revelation so ambiguous or catastrophic that it demanded that the audience keep watching if for no other reason than to find out what happens next.

In the case of Breaking Bad, the pilot unravels like an exercise in how much tension one can fit into 50 minutes of television. Years removed, I still recall how it started with a near naked Walter skidding through the desert in a Winnebago before quickly unveiling the most extenuating circumstances a high school chemistry teacher could possibly find himself in: a terminal cancer diagnoses paired with a pregnant wife, special needs son, DEA agent for a brother-in-law, and meth dealer for a former student, paired with an intimate familiarity with DIY amphetamine recipes. The pilot ends with a drug deal gone bad, paired with an explosion and car crash, one whose resolution doesn’t come about until episode two.

The same strategy can apply in a novel: just when a reader is most likely to put down a book and walk away (i.e., at the end of a chapter), give them an unresolved event whose upshot could go any number of ways, or foreshadow a future plot twist in the works. I used this strategy in the opening chapter of The Band too, when a Kpop boy bander on the verge of worldwide cancellation offers to disappear but whether he does or not doesn’t get revealed until later. Alluding to an unknown but potentially disastrous future keeps an audience intrigued enough to come back, but it’s nothing new—Shakespeare famously did it with the three witches in Macbeth; God himself apparently did it with his many Old Testament prophets.

I know better than to assume what works in one exceedingly popular medium won’t apply to another.

More recently, during a writing class, multiple students brought up their love for the Hulu’s hit show, The Bear. It took watching a grand total of one episode to change the way I write and edit dialogue. By then I already knew that my favorite propulsive writing across genres combines action, narrative, and dialogue, but the trick had always been how to strike the perfect balance between the three.

Hulu’s The Bear shows us how we don’t actually have to pick—the dialogue scenes seamlessly blend all of the above. Turn on any episode and you will likely find Jeremy Allen White’s chef character talking rapidly to another member of his restaurant staff. The dialogue is ostensibly the focus, but the reason the show is so addictively watchable is because something is always going on in the background that requires urgent attention—a receipt machine is furiously spitting out orders, or inspectors are coming, or food is burning.

The same technique can be used in writing: the best dialogue scenes don’t just involve characters talking, but doing, even if it’s something as mundane as putting food on a plate (which, as The Bear demonstrates, can be as tense as any action scene). In The Band, during longer stretches of talking between the therapist narrator and Kpop anti-hero, the two are making tteokbokki when the narrator’s husband walks in on them. Action raises the stakes of dialogue, making it a conversation the reader just can’t walk away from.

There’s this old saying among bookworms: “The book is always better.” Granted, they’re usually talking about movie adaptations, but I would contend that good television can have as much artistic merit as any literary masterpiece. After all, art is art. Once upon a time, I thought it was important to distinguish between ”low-brow” (television) and “high-brow” ones (like literary fiction) because the critics of these various forms always occupied different corners of the newspaper, or online publication, or Tiktok.

But now, after having spent enough time in the ring, in the day to day grunt of fashioning people, places, and things out of thin air and exposing them to the elements to see how they fare or what comes of them—I know better than to assume what works in one exceedingly popular medium won’t apply to another. As The Office, Sopranos, and The Bear have shown us time and again, TV might just be the best writing teacher we didn’t know we needed.

__________________________________

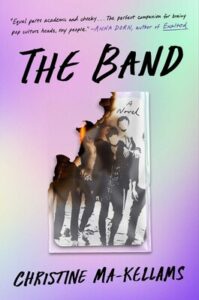

The Band by Christine Ma-Kellams is available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Christine Ma-Kellams

Christine Ma-Kellams is a Harvard-trained cultural psychologist, Pushcart-nominated fiction writer, and first-generation American. Her work and writing have appeared in HuffPost, Chicago Tribune, Catapult, Salon, The Wall Street Journal, The Rumpus, and much more. The Band is her first novel. You can find her in person at one of California’s coastal cities or online at ChristineMa-Kellams.com.