Why Is It So Hard to Talk About Money?

Anna Sale on the Emotional Psychology of Finances and Wealth

Money is like oxygen. It surrounds us, flowing in and out of our lives—and when you’re short of it, nothing else matters. Money is how we put food on the table, how we take care of people we love, and how we invest in all the things that express who we are. But money is also about so much more than what we buy. Money influences how we feel we stack up compared to others. It warps how we see our present and future, with either hope or dread. When it comes down to it, money often determines our very worth—in the deepest sense of the word.

“It is emotional and it’s also this concrete thing,” financial therapist Amanda Clayman told me on Death, Sex & Money. “It’s two things at the same time. It’s both a symbol and a tool.”

Amanda hosted a spinoff of Death, Sex & Money during the Covid-19 pandemic as unemployment numbers started to spike. The idea began when the team and I looked around for honest conversations about this dual nature of money and we couldn’t find them. We wanted to hear people confront the reality of their money—what they had and how that was changing—and explore how those numbers fit into their values and sense of identity. People need this, we thought.

At least I definitely do.

“It’s a big taboo topic, and we’re not used to having that conversation,” Brad Klontz, a psychologist and certified financial planner, told me. He cofounded the Financial Psychology Institute in 2014, after he finished grad school with overwhelming debt and found himself alone with the mental burden of it.

“I had no desire to become an expert in financial psychology. What I wanted to do was find the expertise already written and read it and then move on, but when I looked into the field of psychology, the topic of money had been totally ignored.”

One of my goals is to help us all be a little more honest about the emotional weight of money. Because, gauche as it may be, money is always there, forcing you to think about what it means to you (symbol) and how you choose to use it (tool). When we make financial decisions with someone else, or financial decisions that affect someone else, most of us are inexperienced at being direct. These are big, consequential conversations in intimate relationships—about what we value, how we feel safe, what our obligation is to others. It can take time and attention to root out the odd habits and meanings we’ve developed around money over the course of our lives. But without doing so, and without having the hard conversations that follow, we can’t get into the gritty work of making intentional money choices with our loved ones.

When it comes down to it, money often determines our very worth.In our most intimate relationships, though, at least we have the context that comes with close proximity to each other’s spending and saving habits. When we move out of the private sphere of the household and into our circle of friendships and work colleagues, our sense of each other’s money lives becomes more opaque. Even with people we’re quite close to, everyone has an incentive to emphasize sameness more than difference.

If you’ve ever had a friend inherit a sudden financial windfall or a family member run into dire financial straits, you’ve felt that slight chill of tension where there was once ease. But, I argue, the most honest and helpful conversations about money linger in those spaces of difference. They’re how we see where we can help one another, and also help us understand how money is working in our lives with greater context.

We may think we’re being polite by staying mum, but there are real costs to evading the reality of money for the sake of social comfort. Talking to colleagues about salary ranges and negotiations helps ensure you’re not underpaid. Asking for help when you’re in a crisis helps harness financial resources, and emotional resources, that you wouldn’t know about alone. Sharing money stories also exposes the structural forces that enable some people to sail along and cause others to struggle, even while working identical jobs. Honest conversations about money can bring you more clarity, and more money.

The risk that stalls most money conversations is our fear of how we will look compared to the person we’re talking to. We do a lot of sleight of hand to obscure how we’re doing financially; this is true from our most intimate relationships to our national politics. We live in an era when tech billionaires wear jeans and sneakers, struggling people carry designer purses, and doctors and lawyers are drowning in student loan debt.

We avoid and evade because, even in a time of surging income inequality, no one wants to be an outlier in America. Most of us want to present ourselves as part of the honorable, hardworking middle class.

“Despite evidence of rising income inequality in recent years,” the pollster Gallup reported in June 2017, “Americans are no more likely now than in the past to identify themselves at the high or low ends of the social class hierarchy.” This is the way we have thought of ourselves, even as a 2015 Pew Center study found that the middle class is no longer the majority in America.

That’s beginning to give way, pushed by protest movements like Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter that have demonstrated how not every American has a fair and equal shot at success. In a 2020 NPR/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation poll, more people thought it was getting harder in the United States for an average person to earn a middle-class income, rather than getting easier or staying the same. This survey was conducted, NPR noted, just as the Census Bureau was reporting that income inequality in the United States had hit another record high.

Still, our deeply ingrained beliefs around money, and how we get it, are remarkably durable. In that same NPR poll, people across income levels were most likely to cite “hard work” as an essential driver of financial success. They also overwhelmingly said the American Dream is still attainable for their children and grandchildren. (70 percent of people earning less than $35,000 believed that, and the rates went up from there by income.)

We are confused about how we see ourselves collectively, so no wonder our interpersonal conversations about money can be so muddled! In our private lives, we do all sorts of verbal gymnastics to avoid the simple truth that, at any moment, how much money any of us has is the result of both our personal actions and many larger forces far beyond our control. Your financial situation depends on everything from the broader economy, to the year in which you were born, to the conditions for your parents and grandparents, to the whims of illness, injury, and chance.

“Wealth, not income, is the means to security in America,” Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote in the New York Times Magazine as she made her case for reparations for Black Americans. “Wealth is not something people create solely by themselves; it is accumulated across generations.”

When I’m interviewing people on Death, Sex & Money about their financial situations, I try to keep this in mind. I weigh how I’m emphasizing their personal choices against the systems they’re a part of. If I ask too many questions about how someone decided to borrow money to attend an expensive school, for example, am I somehow letting policymakers and college administrators off the hook for shifting so much of the higher education burden onto students and their families? When it comes to money, our political debates tell us that we either condemn the systems and structures, or we condemn people’s personal decisions.

This is a false choice. Each of us has acquired spending and saving habits, yes, but we are also helped or hurt by generational timing and the wealth or debt we happened to be born into. On top of that are the biases about whose work, time, and ideas are more valuable. Without being specific about the ways all these factors comingle, we chalk up big wins or shameful losses to our own personal characteristics. But that’s not how money works.

The lasting goal of hard money conversations, then, is to identify which parts of our money worries are within our control and which aren’t. We make personal money choices in the midst of larger systems: everything from the cost of housing to tax policy to social safety net priorities. Interrogating these systems is what drives our political movements and debates; and one-on-one conversations are not going to solve them. But by understanding where we are situated in these systems, we can shift some of the mental burden off our bank accounts.

When you talk about the larger context of your own money situation, it becomes easier both to give and to get help. It’s easier to ask for help because your particular challenges aren’t just personal anymore, and it’s easier to give help because you see how your good fortune is not just the result of your cleverness, so you ought to pay it forward. The best conversations about money make room for both the structural forces and our personal choices. They reveal the different histories that are part of our financial identities, along with the varied personalities and values we bring to our financial choices. When we can look at both aspects clearly, it becomes a lot easier to turn the conversation to practical dollars and cents.

It might seem byzantine that we often have to wade through so many layers just to talk more surely about the electricity bill. But that’s why money is so tricky to talk about. And that’s why the rule number one is this: the best place to start any money conversation is to admit that money is about much more than money.

__________________________________

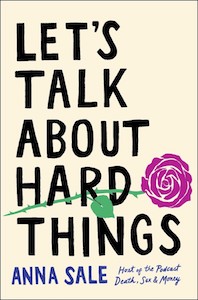

Excerpted from Let’s Talk About Hard Things. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Anna Sale.