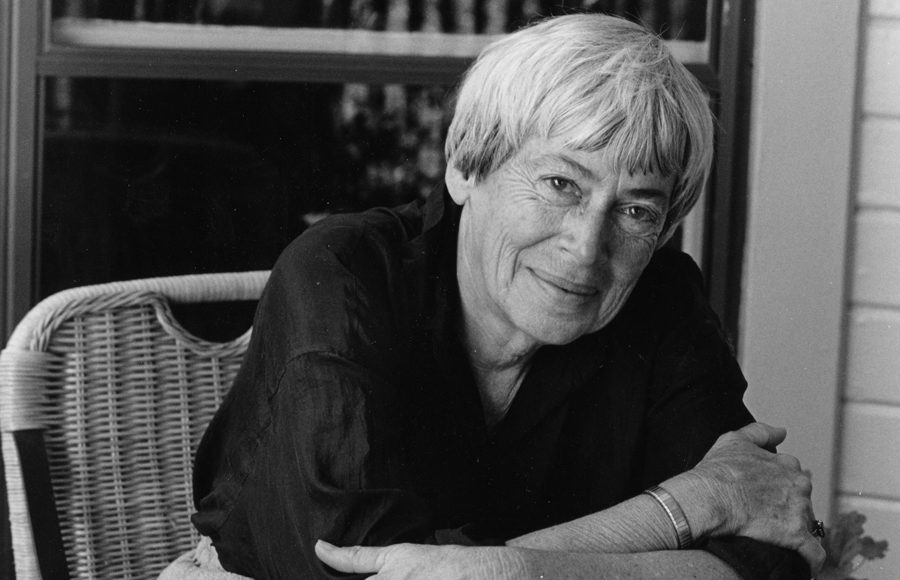

Why I Decided to Update the Language in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Children’s Books

Literary Executor Theo Downes-Le Guin on What That Means For Readers, Past and Future

In a 1973 letter to the editor of The Horn Book Magazine, my mother, Ursula K. Le Guin, took Roald Dahl’s books to task. While acknowledging her own “feelings of unease” about Dahl’s work, she remarked that “…kids are very tough. What they find for themselves they should be able to read for themselves.” I had this in mind as I read about wording changes in new editions of Dahl.

As Ursula’s literary executor, I recently faced a similar decision. My mother, known for her young adult and adult novels, also wrote several children’s books. A multigenerational fan base has kept her Catwings books in print in the US since the 1980s. I was excited to move the books to a new publisher last year.

As we began work on the new editions, I received an unexpected note from the editor: “I’m writing to propose several minor changes to the language… to remove words that now have a different connotation than when the books were originally published.” The words in question were “lame,” “queer,” “dumb,” and “stupid,” a total of seven instances across three books.

I genuinely didn’t know what my mother would have decided. But she left me a clue: a note over her desk asking, “Is it true? Is it necessary or at least useful? Is it compassionate or at least unharmful?”

Ursula revised herself throughout her career, notably The Left Hand of Darkness, which takes place on a planet where sex and gender are fluid. Years after publication, during a later wave of feminism, she received criticism for the novel’s use of “he” as default personal pronoun. After some defensiveness, Ursula demonstrated, through essays and revisions of the text, how she might have approached things differently.

My job is to bring my mother’s work to new generations of readers, not to revise it. People who adore a book are often eager to transform it, through screen adaptation, fan fiction or critical reinterpretation. Sometimes this works well; often it doesn’t. I tend to start from the position that Ursula’s words are sacred, so my initial reaction to the editor’s request was that of a strict constructivist.

After deep breaths, and with Ursula’s own revisionism in mind, I contacted a disability rights attorney, a youth literature consultant, a racial educator, and some kids. My advisory group leaned toward change but was not in consensus. I genuinely didn’t know what my mother would have decided. But she left me a clue: a note over her desk asking, “Is it true? Is it necessary or at least useful? Is it compassionate or at least unharmful?”

I like to think that truth and compassion are immutable even as the language we use to express them changes. But cultural constructs of harm are mutable; we frequently revise our definition of what’s harmful to whom, how it is spoken of, and who gets to do the speaking. My mother’s note tipped me toward changing her words. I found substitutes that would retain the original meaning and cadence, and stipulated to the publisher that the new editions would note that the text had been revised.

People who don’t share my sensibilities about artistic freedom seem to prefer to ban or burn books, usually without having read them.

Criticism of changes to Dahl’s books can just as well be leveled at my own decision. Closest to my anxiety is the reaction of Susanne Nossel, of PEN America, who counsels us to “consider how the power to rewrite books might be used in the hands of those who do not share their values and sensibilities.” Although this haunts me, people who don’t share my sensibilities about artistic freedom seem to prefer to ban or burn books, usually without having read them.

Most of the criticism regarding changes to Dahl’s words is of the “slippery slope” variety, which in itself tends to be reductive. The decision to revise a book need not create a prescription for all books or all writers at all times. It may pay heed to who is being revised, the reasons for the proposed revisions, the extent of change, and especially who is doing the revising—for example, a corporation that controls the rights vs. the author or an heir. These factors all determine when we shift from revision to wholesale rewriting.

Dahl and my mother could not be more different as writers and as humans, but they had in common a profound trust and affection for their child readers. Consistent with that posture, I would say that kids intuit and accept better than adults that language is constantly in flux, as are human sensibilities. Not condescending to young readers also means trusting that they can glean meaning from a textual whole, not just from specific words.

Theo Downes-Le Guin

Theo Downes-Le Guin is trustee of the Ursula K. Le Guin Literary Trust.