Why Fig Pollination and Literary Criticism Have a Lot in Common

A. V. Marraccini Considers the Critical Gaze, Eroticism, and the Generative Third Body

Here’s a weird thing about some kinds of figs: there are male and female figs. The fig is an inverted flower, which needs to be pollinated to make the fig fruit that we eat. There are male and female fig wasps. The female fig wasp burrows into the male fig, called the caprifig, and the process, in turn, is called caprification, when she lays eggs and those eggs hatch. The hatchlings are blind, flightless males and young females. They have incestuous sex. The now pregnant female wasps, the ones Aristotle and Theophrastus call psenes, burst out of the skin of the caprifig and go off to burrow anew into other figs. Both erroneously thought this was a kind of spontaneous wasp generation, but to be fair the actual mechanism is hard to discern such that the biology of it is still a topic now.

The female fig needs to be pollinated to fruit. Bees can’t do this, nor wind, because the inverted flower is sealed up inside itself. So sometimes a female wasp doesn’t crawl into a male fig, where she can lay eggs. Sometimes she crawls into a female fig, where she starves and dies, but in the process pollinates the inverted flower, which can then fruit. The body of the wasp is absorbed by the growing flesh of the fig. You do eat it, in a sense, but you wouldn’t know if I hadn’t told you.

This is called commensualism, a form of parasitism in which the parasite doesn’t actively harm the host. More properly, it’s even a mutualism, dead wasps and male fig husks aside, because the fig and the wasp need each other to reproduce.

*

I am somehow reading Updike’s The Centaur, which makes me think this is what it must be like to be the caprifig, the male fig the female wasp lays eggs in:

“The pain extended a feeler into his head and unfolded its wet wings along the walls of his thorax, so he felt, in his sudden scarlet blindness, to be himself a large bird waking from sleep… The pain seemed to displacing with its own hairy segments’ his heart and lungs…”

*

But I’m not the fig, I’m the wasp. I burrow into sweet, dark places of fecundity, into novels and paintings and poems and architectures, and I make them my own. I write criticism, I lay it in little translucent eggs. ερινασμός. Caprification. Criticism is a mutualism as parasites like me go, or at least a commensualism, pollinating novels to make more novels; Winckelmann’s halls of beautiful young men in Greek sculpture making the hot breath of living beautiful young men into bildungsroman, which in turn end up in marble of their own. The critical gaze is tearing apart, clawing into the soft central flesh of the tree bud.

The critical gaze is tearing apart, clawing into the soft central flesh of the tree bud.

The critical gaze is also erotic; we want things, we are by a degree of separation pollinating figs with other figs by means of our wasp bodies, rubbing two novels together like children who make two dolls “have sex”, except we’ll die inside the fruit and someone else will read it and eat it, rich with all the juices of my corpse. This is an odd but sensuous thing to want.

And though the male-female figs exist, and the male-female wasps, the whole process, the generative third body in the dark recesses of the inverted flower, is somehow queer. Criticism, too, is queer in this way, generative outside the two-gendered model, outside the matrimonial light of day way of reproducing people, wasps, figs, or knowledge.

*

I lied when I said I was “somehow” reading The Centaur. I’m reading it because one of the people who taught me, who formed me into a wasp instead of a bee or a wind, had just read it. He says it is about fathers and sons, about being both. I will never be either. I think about Chiron and Achilles, rather than Prometheus, to whom the novel refers.

Chiron, the centaur, was responsible for the education of Achilles. Patroclus, too, though he seems to have more or less tagged along for the ride. Anyhow, Achilles thinks of Chiron as a sort of-father, at least in Statius, where Achilles sleeps entwined around Chiron’s shoulders. There are numerous paintings of this, the education out in the rocky woods. It is no surprise they are often homoerotic— the beautiful young man, still soft before the great war at Troy, made keen-edged by the older, fiercer, inhuman centaur. The frisson as Chiron leans over Achilles, bowstring taught with an arrow about to loose!

You don’t become a fig wasp on the flanks of the neoclassical tradition without having inhabited it, parasitized it yourself first as practice. This is an education. You tell yourself you are Achilles (or sometimes, Patroclus), you rationalize your world with these models, themselves parasitic on a tradition that you did not yourself make. You learn to be by being them, by pushing into them and unfolding your wet wings.

The critical gaze is also erotic; we want things, we are by a degree of separation pollinating figs with other figs by means of our wasp bodies, rubbing two novels together like children.

This displacement makes me shiver, a kind of longing by proxy. You learn to be an aesthete by honing everything out in some wilderness, where no one sees your missteps, your clumsy formation. I will never be a father or a son. I am not yet Chiron, but I have been Achilles. An education in this way is good practice for being a critic, for inhabiting and bursting out of galls and personae like the psenes.

The critical education, the mapping and re-mapping of the self onto the others of art or canonical literature, onto the Achilleses hanging ripe and easy on the trees, this, too, is an erotics. For everyone you could possibly be, for knowing how to be, for being taught how to know in this way that feels forbidden, queer, like an ekphrasis of somebody else’s kiss on somebody else’s vase, for the remove makes it only sweeter. You need a centaur to teach you how to both inhabit and step outside your own human-ness, to make it that contrafactual, malleable stone, and quick as a horse’s rear legs jutting out of the marble of a metope.

Hence, Chiron. Hence, Achilles. Hence, myself on a cold November afternoon, looking for something in Updike by sheer force of will, of wanting to be the sort of person who can find it, those crystalline-soft particles of pollen. Learning to be a parasite is the crucible of unmet longing for that something-else that can complete you, infolded somewhere, still perhaps hidden.

______________________________

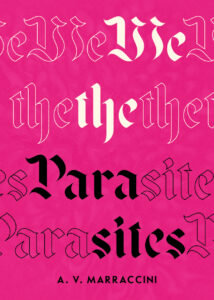

Excerpted from We the Parasites by A. V. Marraccini, available from Sublunary Editions

A. V. Marraccini

A.V. Marraccini is a critic, essayist, and historian of art. In addition to her scholarly work, she has written on both visual culture and literature for publications ranging from the TLS and the LARB to BOMB magazine and Hyperallergic.