17th-Century Dildo Shopping with the Ladies: On the Contested Terrain of Early Modern Desire

Annabelle Hirsch Explores the History of Female Self-Pleasure

Set out in search of the history of women’s relationship with sex and you will—with a bit of luck—find a very amusing engraving from the seventeenth century lurking in the shallows of the internet. It shows three young women standing at a sales counter.

You could be forgiven for thinking they’re at a regular weekly market, except that in the places where cheese, salami, fruit, and vegetables would normally go, there hang instead a selection of penises. Big and small, thick and thin, any shape you could ever imagine or wish for. Behind this display stands a woman who appears to be explaining each one in detail.

The two women at the front are pointing at a couple of examples with interest, no doubt asking, “Oh, and what can that one do?” while the third woman hovers in the background, tearing her hair in excitement and—one can only hope—anticipation.

Throughout history, female sexuality and female desire have been tricky terrain.This picture comes from the English translation of one of the first French handbooks of its kind: the École des Filles ou la Philosophie des Dames, in English The School of Venus, or The Ladies Delight. What exactly constituted a lady’s “delight” at that time, we cannot say for certain. Throughout history, female sexuality and female desire have been tricky terrain, heaped with shame, fear, and many a myth.

In the late eighteenth century, for example, the medical profession began the rumor—which stubbornly persists to this day—that women fundamentally don’t enjoy sex, are only out for relationships, and will commonly feign a migraine in order to evade their duty. Yet in all the preceding centuries, people had believed quite the opposite: namely that women were wild, hypersexualized creatures—animals, almost—who were at the mercy of their own urges and would fall on anything and everything if not restrained and monitored for their own safety.

It was for this reason that cucumbers, eggplants, and similarly phallic vegetables were strictly off the menu in many convents. Even Ovid, writing in antiquity, claims that women feel around nine times as much desire as men.

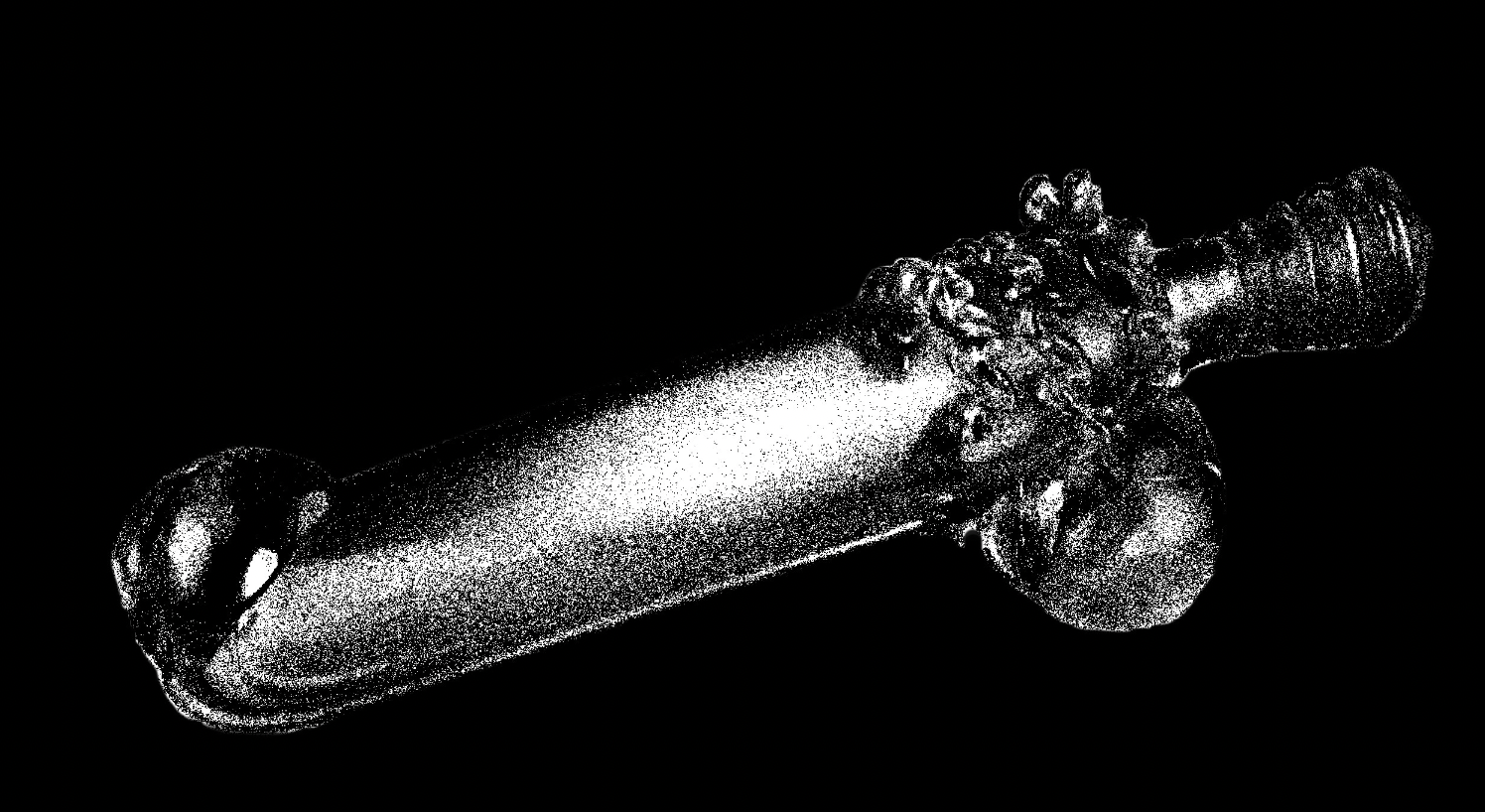

Nowadays we’d probably agree without hesitation, but what did the women of early modern times think about their appetites? Did they believe what men told them and feel afraid of their alleged sexual unpredictability? Or did they laugh among themselves about the husbands for whom their female potency was clearly too much? Did they complain, like so many women today, that men—despite all claims to the contrary— just didn’t want it as often as they did? We don’t know. At any rate, they seemed not to want to wait around for a man to “do them the honor” in his brusque and no doubt less than satisfying manner, as suggested by the object pictured below: a sixteenth-century dildo.

As already mentioned, Venice was in those days what you might call the capital of refined sex. Accordingly, the glass-blowing island of Murano was known not just for its famous chandeliers, candlesticks, glasses, and other pretty objects—but also as a dildo factory. In a well-to-do household, masturbation (if indulged in) was to be aided by the very finest glassware, if you please, despite the fact that onanism was second only to coitus interruptus—which, incidentally, is linked in the Bible to the story of Onan—as the Church’s worst nightmare.

Masturbation was a sin to be punished. Even sex itself was extremely problematic at the time. In principle, it was a sin, but if you did do it, it needed to serve a purpose—namely reproduction—which meant that any practices that wouldn’t result in a child were ruled out by default. So: no fellatio, no cunnilingus, no sodomy, no coitus interruptus, and, of course, no masturbation.

Sex itself was extremely problematic at the time. In principle, it was a sin, but if you did do it, it needed to serve a purpose.From the Church’s perspective, sex was a box to be ticked rather than a way to have fun. At least when it took place within a marriage. Outside this union, and depending on which century you were in, it could be regarded with a slightly more relaxed attitude.

In the Middle Ages, for example—and this was very much in accordance with the idea of courtly love—the general opinion was that passion and marriage should have nothing to do with each other, that sex could most certainly be pleasurable, just not at home. Coveting your own wife was a sin, as it were, with one particularly blinkered priest writing that there was nothing more despicable than a man who loved his wife as he would a mistress.

The likelihood of women finding sex with their husbands boring, or being frustrated by the rarity of the act, was therefore pretty high, all the more so as they were allowed to do it in only one position: missionary. Lilith, Adam’s first wife, had tried to take measures against this, as we all know, and actually preferred to quit paradise altogether rather than submit to the position of “board” for all eternity.

The women of the early modern era found less radical methods. During the brief wave of libertinism, some high-society ladies did have lovers. But those who found the risk of compromising their reputation and livelihood too great (while men have always been able to cheat to great acclaim, women have not) survived attacks of acute boredom by reaching for objects like this one. The sex-toy business seems to have experienced a small boom in the seventeenth century: dildos were produced in greater numbers and various materials; some could be filled with liquid to simulate ejaculation.

And maybe these phalli weren’t used exclusively for self-pleasuring but, over time, came to occupy a place in marital sex. For one thing, after the Reformation there was generally a renewed appreciation of marriage; partners were encouraged to show each other love and affection in fulfilling sexual relationships that weren’t aimed solely at making babies. And for another, from antiquity all the way to the late eighteenth century, many social circles were of the pleasing persuasion that a woman could get pregnant only if she had an orgasm. Why else would God have given her orgasms?

To the minds of many, female desire was an essential component of conception. In 1740, for example, the Austrian empress Maria Theresa received some friendly advice from her doctor: she shouldn’t fret too much about producing an heir, he said, but should simply let her clitoris (a discovery of the previous century) be “tickled” a bit in bed. With success, it seems: she became not just an outstanding ruler but also a mother sixteen times over.

Looked at this way, we can assume that even the most pious husbands at least occasionally made a bit of an effort—especially as it was said that the prettiest children were conceived through mutual climax. Those who were denied this experience might have reached for one of these glass contrivances. Or repurposed their glass penis as a “drying rack”—for the condoms made from animal intestines that gradually went on sale in the eighteenth century.

__________________________________

Excerpted from the book A History of Women in 101 Objects by Annabelle Hirsch. Copyright © 2022 by Kein & Aber AG Zurich—Berlin. Translation copyright © 2023 by Eleanor Updegraff. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.