Why Do We Love Joni Mitchell the Way We Do?

On the Sound of Something New in 1970s L.A.

Joni Mitchell was admitted to hospital by ambulance last week. She had recovered consciousness by the time she got there, but things didn’t sound too promising.

Social media immediately went into overdrive, as they tend to in such circumstances. Favorite Mitchell songs were posted. Get-well messages were exchanged competitively. And there was great speculation as to the nature of Mitchell’s incapacitation, based on no medical information whatsoever other than the fact that the musician/writer/painter is known to have smoked like a chimney since childhood and suffers from a self-diagnosed but not medically recognized condition called Morgellons disease, which creates in its victims the illusion that their flesh is infested with parasites.

There was superheated prose knocking around, too. Eve Barlow, writing on the British internet platform The Pool, threw herself down upon the cold linoleum floor beside Joni’s bed in Intensive Care: “We haven’t exhausted her candid wisdom yet,” she keened. “Joni knows us better than we know ourselves. She’s our mother, complete with answers to questions we haven’t yet thought to ask. I’m intimidated just writing down the name ‘Joni Mitchell.’ She would write it down better, somehow making the words even more profound.”

Me, I just felt sad—but also slightly confused and disorientated, as if “sad” were inadequate somehow. In fact I felt really quite odd. I got pictures in my head of Mitchell coming to in the ambulance, her pharaoh’s overbite working crossly and her pale eyes flashing distress, one hand—her better hand—perhaps flapping impatiently at the non-arrival of the words she wants to say. I wondered what she registered in that moment of regained consciousness, and whether she thought about herself in the second person. I wondered whether she was filled with poetry or just curses and banality, the whole damn farrago being one prosaic experience too many, not to be dignified with careful language. I got into my car to go to Sainsbury’s and listened to Hejira to remind myself of her genius.

It didn’t help. Hejira just said the usual stuff, about flight, about sex, about the urge to keep on going. I pushed a trolley around Sainsbury’s and experienced the low-frequency hum of anticipatory mourning while I counted bananas. How does one lament the passing into shade of a force like that? How does one let go of Joni Mitchell?

With difficulty, I find, because she has seemed so real and concrete and permanent in life, so much a part of one’s own fabric, and yet also so manifestly a creature of invention, her own diligent invention: a woman apparently self-conceived and created and then reimagined by herself over and over again in her slippy fight with her self-loathing, almost as full of detail in the memory as one’s own mother. Not that I have ever felt mothered by Joni. Over the decades she has seemed as narratable as Helen of Troy, but rather less warm to the touch.

In fact, to be entirely fair, I have never had any interest at all in her personal life and still less any authentic concern for her legend, which has seldom seemed all that attractive to me, expressing, as it does, so many of the least appealing aspects of West Coast American countercultural celebrity. Despite the feeling that I “know” her well, I have never felt the slightest inclination to wonder what she’d be like to have as a friend or neighbor in some parched canyon. I haven’t always liked her voice much either. I have been wholly immune to her as a person and have only ever taken in her songs selfishly.

Yet she has occupied my psyche for nearly 40 years with a tenancy more robust and demanding than that of any other singer-songwriter. She has occupied it passively, but tenaciously. I cannot shake her out of there. She will not leave. It’s as if she took up residence in my chambers at some unnameable point in the distant past and just settled in, with a sense of entitlement you might expect only from family. Heaven only knows what I’ll feel when she actually dies and leaves me to deal with what’s left behind. Doubtless, it will amount to more than a terracotta army of pot plants and a manky cat.

*

Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment.

In fact it now appeared that Mitchell was unable to cadence a phrase without approaching the notes like a hostess at a cocktail party, swooping up to them with a swish in an airburst of expensive perfume.

She’d already done the itinerant North American folk thing for most of the previous decade—silvery footage of her tooting “Urge For Going” on mid-60s Canadian folk TV is easily traced on YouTube. But she was already leaving that world by the time David Crosby of the Byrds hitched her to the Californian counterculture wagon. By then, other people had had hits with her songs—notably Judy Collins’s “Both Sides, Now”—and LA’s Laurel Canyon had become Mitchell’s home and her cathedral, along with the rest of her adopted tribe of nesting longhairs. As a kinship group, they were quietly intent on contemplating the devolution of the 60s “dream,” cannily accepting their status as seers of a disappointed new age and settling into mellow self-absorption, as into a great wicker armchair on the stoop at sunset. Mitchell seemed at the time to be the established priestess of the tribe, consecrated into her role.

But she was nothing of the kind. She had management—Elliot Roberts and David Geffen—and she had an urge for going.

Blue in 1971 is where you feel the clutch start to bite. It is a stark record for a golden girl to make. It came out the year after “Big Yellow Taxi” was a hit and it became an instant archetype of the “confessional” singer-songwriting style (a term Mitchell despises, incidentally, for its implicit associations with guilt and religious coercion). A cult arose around it. If Mitchell herself represented a certain archetype of hippie femininity, Blue was an archetype of female expressivity: inward-looking, self-exposing, delicate, emotionally forensic, anti-triumphal . . . On first contact with it, you feel almost obliged to sit down and close your eyes, hands together, head inclined, all the better to experience the searching sensitivity of it all. And while it’s true that Blue contains passages of brilliant writing and is without real rival for the rawness of its excavations of the soul wounded by love, it is easy now to feel that it was always destined to be une vache sacrée. Perhaps even that it was designed that way. Some of the melodies feel arched for display, like the tail feathers of a courting bird; some of them skim the ceiling of the singer’s vocal range and threaten to leave by the window, as if the real motive for their creation were to demonstrate that Joni’s supple contralto had other more exciting places to go than might be reached in all our dreariest two-a- penny dreams. Beat that, it seems to say. Try going there.

It’s also a record that extended the range and depth of Mitchell’s pianistic songwriting. Writing at the piano (as opposed to guitar) makes different demands on the compositional mind. You can hear her on Blue adjusting her methods to put “The Last Time I Saw Richard” and “My Old Man” together—sitting there on the piano stool, poised in a pall of artful creativity, breaking the chords into arpeggios, fingering them methodically out, trying to think big and artistic as befits the elevated status of the ivory keyboard.

Please do not misunderstand me: I think Blue is a marvel. “All I Want,” “A Case of You,” “River,” “Blue”—these are songs for the ages. If she’d stopped there, Blue would surely have been sufficient to cement Joni into the structure of her times. But she didn’t stop there, because she had much bigger explorations to conduct and longer roads to travel. Other places to reach.

For the Roses appeared the following year, and it sounds like what it is—a hard second-gear acceleration for the horizon. This is no gilded folkie delving into the ruins of her life from the comfort of the wicker armchair but a woman feeling a need to accord with expectation. Mitchell now has jazzers and cellists at her disposal. And she has a selfhood to firm up. We are ushered into a room in which we observe a proud, assertive, judgmental Joni at the piano, exploring the spread of her poetic reach as if it were fanned out in front of her like her hands at the keyboard. The tunes and their arrangements are artful. The voice swoops imperiously. She has plenty to lament. Robert Christgau wrote in the Village Voice: “Sometimes her complaints about the men who have failed her sound petulant, but the appearance of petulance is one of the prices of liberation.” He loved the record.

Meanwhile, on the inside of the gatefold sleeve, an apparently naked Joni stands on a rock, one knee crooked, gazing out into the Pacific, a West Coast parody of Friedrich’s Alpine Wanderer Above the Mists—or perhaps a reverse angle on Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. On the record, she sometimes addresses herself in the second person. She is beginning to enjoy her sophistication.

Then, in 1974, came Court and Spark, which took sophistication by the hand and led it into a newly landscaped uptown park, where it spread out a giant square of French linen on the grass and hosted it to a picnic, a proper West Coast Déjeuner sur l’herbe. The sessions were held with an array of fully clothed musicians, some of them kind-of-jazzers, some of them sort-of-rockers, some of them a cultivated hybrid of the two, and they locked into the uptown-downtime groove like men of the world. What a picnic. Mitchell’s voice now found itself, by its own volition, at the center of a high-tone ensemble and the tastefulness all around was as a frame to the naked elegance of her phrasing. The cellos were joined by reeds. The reeds were teased out into choric eloquence by arrangements that might have sat well with Sondheim. In fact it now appeared that Mitchell was unable to cadence a phrase without approaching the notes like a hostess at a cocktail party, swooping up to them with a swish in an airburst of expensive perfume.

Court and Spark is a brilliant parade of accomplishments, both musical and literary. The album radiates a cool, artful, bodiless glow, making a case for itself as the most soigné musical achievement of its era—so knowing and refined is its range, in fact, that it’s not always possible to hear where Mitchell’s internal landscape ends and where LA begins. It’s a continuum, from she to shining sea. The songs might profess disdain for the superficial and the shallow but both irony and sincerity, as well as old-fashioned heart, are sometimes lost in the shimmer. The voice merely hosts the soirée—and swoops graciously up to its desired notes from below, to remind you of its silken command.

![]()

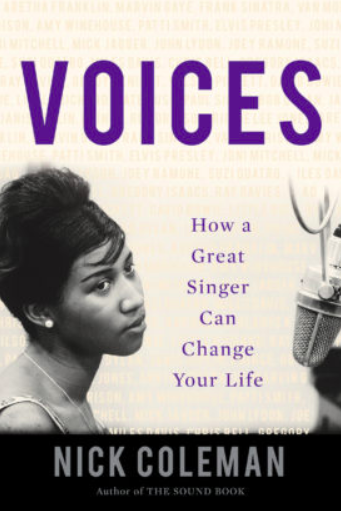

From Voices: How a Great Singer Can Change Your Life by Nick Coleman, courtesy Counterpoint. Copyright 2018, Nick Coleman.

Nick Coleman

Nick Coleman following a brief spell as a stringer at NME in the mid-1980s, was the music editor at Time Out for seven years, then the arts and features editor at the Independent and the Independent on Sunday. He has also written on music for The Times, The Guardian, The Telegraph, New Statesman, Intelligent Life, GQ, and The Wire. He is the author of The Train in the Night, which was short-listed for the 2012 Wellcome Book Prize.