Why Are We So Resistant to the Idea of a Modern Myth?

Philip Ball: “Myths are promiscuous; they were postmodern before the concept existed.”

Why are we still making myths? Why do we need new myths? And what sort of stories attain this status?

In posing these questions and seeking answers, I shall need to make some bold proposals about the nature of storytelling, the condition of modernity, and the categories of literature. I don’t claim that any of these suggestions is new in itself, but the notion of a modern myth can give them some focus and unity. We have been skating around that concept for many years now, and I can’t help wondering if some of the reticence to acknowledge and accept it stems from puzzlement, and perhaps too a sense of unease, that Van Helsing is a part of the story. Not just that movie, but also the likes of I Was a Teenage Werewolf and Zombie Apocalypse, as well as children’s literature and detective pulp fiction, not to mention queer theory, alien abduction fantasies, videogames, body horror, and artificial intelligence.

In short, there are a great many academic silos, cultural prejudices, and intellectual exclusion zones trammeling an exploration of our mythopoeic impulse. Even in 2019, for example, a celebrated literary novelist dipping his toe into a robot narrative could suppose that real science fiction deals in “traveling at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots,” as opposed to “looking at the human dilemmas of being close up.” It is precisely because our modern myths go everywhere that they earn that label, and for this same reason we fail to see (or resist seeing) them for what they are. As classical myths did for the cultures that conceived them, modern myths help us to frame and come to terms with the conditions of our existence.

Evidently, this is not all about literary books. Myths are promiscuous; they were postmodern before the concept existed, infiltrating and being shaped by popular culture. To discern their content, we need to look at comic books and B-movies as well as at Romantic poetry and German Expressionist cinema. We need to peruse the scientific literature, books of psychoanalysis, and made-for-television melodramas. Myths are not choosy about where they inhabit, and I am not going to be choosy about where to find them.

*

The idea of a modern myth, admits literary critic Chris Baldick,

simply should not exist, according to the most influential accounts of what a ‘myth’ is . . . the consensus in discussion of myths is that they are defined by their exclusive anteriority to literate and especially to modern culture. ‘Myth’ . . . is a lost world, to which modern writers may distantly and ironically allude, but in which they can no longer directly participate.

Like Baldick, I think this traditional view is entirely the wrong way to understand what a myth is. I will try to explain why.

The word myth is bandied about with dreadful abandon, as if it doesn’t much matter what it means. Often now it is used to stigmatize a widely held misconception: the myth that the moon landings were staged in a Hollywood studio, or that Nelson Mandela died in the 1980s, or that eating carrots improves your eyesight. It can mark a clumsy attempt to disguise a franchise as an epic: Star Wars is mythic, right? (We’ll see about that.) Or perhaps a story becomes a myth just by being much retold?

Why are we still making myths? Why do we need new myths? And what sort of stories attain this status?

Experts, I fear, aren’t much help here. You can collect academic definitions for as long as your patience lasts. “The word myth,” as Northrop Frye rightly says, “is used in such a bewildering variety of contexts that anyone talking about it has to say first of all what his chosen context is.” Folklorist Liz Locke put it more bluntly in 1998: “such a state of semantic disarray and/or ambiguity is truly extraordinary.”

Finnish folklorist Lauri Honko nonetheless gives a definition that kind of sounds like what you’d expect from an expert: a myth is

a story of the gods, a religious account of the beginning of the world, the creation, fundamental events, the exemplary deeds of the gods as a result of which the world, nature and culture were created together with all parts thereof and given their order, which still obtains. A myth expresses and confirms society’s religious values and norms, it provides a pattern of behavior to be imitated, testifies to the efficacy of ritual with its practical ends and establishes the sanctity of cult.

This is a fair appraisal of how myth has often been regarded by anthropologists. But it is fraught with dangers and traps. Like the word “anthropology” itself, it seems to offer an invitation to make myth something “other”: something belonging to cultures not our own, and most probably to ones that even in the circles of liberal academics retain an air of the “primitive.” Gods, creation, ritual, cult: these are surely notions that we in the developed world have left behind and only pick up again with an air of irony. Our “gods” are not real beings or agencies but metaphorical cravings (“he worships money”) or celebrities (rock gods and sex goddesses).

Our rituals, not invested with any spiritual content (except in churches, mosques, and temples attended by the devout), are empty or, at best, time-honored habits we indulge for the social sanction they offer—marriages and funerals, say. Our cults are brainwashing sects isolated from regular society. And so likewise, our “myths” are things that many people believe to be true but that aren’t really—or, as “urban myths,” oft-told tales that likely never happened.

Our popular narrative, then, is that we shed mythology in its traditional sense, probably during the process that began in the Enlightenment, in the course of which the world became “disenchanted” by the advance of science, and that has led since to a secular society on which the old deities have lost their grip. We grew out of gods and myths because we acquired reason and science.

This picture is tenacious, and I suspect it accounts for much of the resistance to the notion (and there is a lot of resistance, believe me) that anything created in modern times might deserve to be called a “myth.” To accept that we have never relinquished myths and myth-making might seem to be an admission that we are not quite modern and rational. But all I am asking, with the concept of myth I use in this book, is that we accept that we have not resolved all the dilemmas of human existence, all the questions about our origins or our nature—and that, indeed, modernity has created a few more of them.

Our popular narrative, then, is that we shed mythology in its traditional sense, probably during the process that began in the Enlightenment, in the course of which the world became “disenchanted” by the advance of science.

One objection to the idea of a modern myth is that, to qualify as myth, a story must contain elements and characters that someone somewhere believes literally existed or happened. Surely myths can’t emerge from works of fiction! The anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski asserted as much, saying of myth that “it is not of the nature of fiction, such as we read today in a novel, but it is a living reality, believed to have once happened in primeval times, and continuing ever since to influence the world and human destinies.”

But this is simply the grand narrative with which Malinowski and his generation framed their study of the myths of “primitive” cultures. It allows us to insist (as they wished to) that we advanced societies have no myth left except religion (and even that is no longer believed in quite the same way as it was a couple of centuries ago). As Baldick puts it, in this view “myth is the quickest way out of the twentieth [and now the 21st] century.”

Even in its own terms, however, Malinowski’s definition is tendentious. Did the author(s) we know as Homer believe he was merely writing history, right down to, say, Athena’s interventions in the Trojan war? To assert this would be to neglect the long and continuing scholarly debate about what Homer was really up to—was he, for instance, a skeptic, or a religious reformer? Worse, it would neglect the even longer and profound debate about what storytelling is up to. It might be unwise to attach any contemporary label to Homer, but one that fits him more comfortably than most is to say he was a poet, and that he used poetic imagination to articulate his myths. Stories like his relate something deemed culturally important and in an important sense “true”—but not as a documentary account of events. Plato admitted as much in the 5th century BCE; are we then to suppose that Greek myth was already “dead” to him?

To ask if ancient people “believed” their mythical stories is to ask a valid but extremely complex question. It is much the same as asking if Christian theologians, past and present, “believe” the Bible. Yes, they generally do—but that belief is complicated, multifaceted, and contentious, and to imagine it amounts to a literal conviction that all the events and peoples described in the holy book occurred as written is to misunderstand the function of religion itself. What’s more, while we can adduce a range of interpretations about these beliefs today, it is not clear we can ever truly decide how these correspond (or whether they even need to correspond) to the convictions of the people who created the original text.

Many early anthropologists and scholars of myth (and some still today) thought that myths must be “sacred”: they must have the aspect of religious belief, and perhaps have been used in ritual. This was the position taken by Edward Burnett Tylor, one of the 19th-century founders of cultural anthropology, and also by James Frazer in his seminal early work on comparative myth, The Golden Bough (1890). For Tylor, Frazer, and Malinowski, myth was a prescientific way of understanding the world, and thereby of trying to control it. The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss argued that in fact myth was a kind of primitive science: logical and concrete in its own terms. Philosopher Karl Popper believed that science arose out of efforts to assess the validity of myth through empirical, rational investigation of its effectiveness. The evaluations of all these commentators stemmed largely from a focus on creation myths, which are the easiest to map onto questions about how the physical world is constituted and governed.

One objection to the idea of a modern myth is that, to qualify as myth, a story must contain elements and characters that someone somewhere believes literally existed or happened.

This view of myth as primarily religious and at any rate prescientific is certainly a convenient way of keeping myth at arm’s length from today’s secular, technologically sophisticated society. But to insist that a religious role is a necessary, defining feature of myth would be an arbitrary stricture that tells us little about the social work myths did. It is a view that mistakes function for process—as if to say that the function of a church service is to enable hymns to be sung. It doesn’t even fit with the way (as far as we can say anything at all about this) myth functioned in ancient times. As classicist William Hansen has said, there is “no real evidence that I can see that the Greeks regarded myths as ‘sacred stories,’ unless you take ‘sacred’ in a very watered-down sense.”

It’s undeniable that religion and myth are tightly entwined, however—not least because both address cosmic questions about meaning, which lie outside the domain of scientific cosmology. For religious scholar Mary Mills, myth offers a “cosmic framework .. . which indicates where cosmic power resides, what it is called, and so how it can be used.” To which one might reply: sure, sometimes. The world emerging from the body of the giant Ymir, maybe. Theseus’s struggles with the Minotaur or Medea, not so much.

The temptation is to suppose that modern myths are today’s replacement for religion. That would be to fall for another a category error, however, for religion might be regarded as a particular social and institutional embodiment of myth—and not vice versa. Religion explores some of the same questions—about life and death, meaning, suffering and fate, origins—and so it is not surprising that we will find our modern, secular myths still returning to religious themes, questions, and experiences. Institutional religion tends, however, to crystallize from this exploration codes of conduct, values, and norms. At its worst, it seeks to escape from the ambiguities of myth by imposing a false resolution to irresolvable questions. At its best, it leaves those doors open.

This brings us to the tidy function ascribed to myth by Honko’s definition: to express and confirm society’s religious values and norms and provide a pattern of behavior to be imitated. This is the sober, objective rationalist’s view of myth as normative narrative. But whose behavior exactly is to be imitated among the Titans and Olympians? Cronus the father-castrator? Zeus the sex-pest and rapist? Dionysius the libertine? Heracles with his boneheaded pragmatism? Self-absorbed Narcissus?

No, myth is not tidy. Myth is the opposite of tidy! Was Gong Gong, who caused the Great Flood of China’s formation myth, a wicked demon king who broke one of the Pillars of Heaven and made a hole through which the waters poured (as some versions suggest)? Or was he an opportunist human king who simply tried to exploit the catastrophe? Or was he an inept engineer employed by the Emperor Yao to drain the waters? Or was he in fact the father of the engineer-hero Yü who finally resolved the mess? Take your pick. This, I think, is the best answer we can give to such questions based on the conflicting versions of myths that have survived (while no doubt many others have been lost): it depends on the story you want to tell. Gong Gong could represent many influences and agencies, contingent on what the myth-teller wanted the people to believe about flood control and state authority.

A myth is typically not a story but an evolving web of many stories—interweaving, interacting, contradicting each other. Boil it down and the story falls away: there are no characters (which is to say, individuals with histories and psychologies),no location, no denouement—and no unique “meaning.” You’re left with a rugged, elemental, irreducible kernel charged with the magical power of generating versions of the story.

It’s undeniable that religion and myth are tightly entwined, however—not least because both address cosmic questions about meaning, which lie outside the domain of scientific cosmology.

A function of China’s flood myth (for example) is thus not simply to give citizens a quasi-religious account of how their nation began, but also—and more importantly—to help them deal with the ever-present fear of massive flooding. It sanctifies the authority of someone who can cope with such a natural disaster, and even proposes a theoretical basis for flood control: carve out channels to let the waters flow, don’t dam them up. But more than that: it creates a vehicle for thinking about the problem, without offering either a definitive version of events or an unambiguous solution. When a myth becomes a dogmatic social and ethical code, it has become prescriptive religion or something like it: we have arrived at Daoism or Confucianism, say.

When a myth permits of a resolution—when it indeed succeeds in what Lévi-Strauss describes as its aim, of providing “a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction” (though how could it, if the contradiction is real?)—it has become a moral fable. But while it retains ambiguity and contradiction, it stays a myth. It acts not as a cultural code but as what cultural historians Amanda Rees and Iwan Rhys Morus call (apropos the kind of modern myths discussed in this book) a “cultural resource.”

It’s unfair to judge the early anthropologists too harshly for the limited and inadequate picture of myth they presented, which was of course a product of its time. They deserve credit for taking seriously the function it serves; as Malinowski said, myth “is not an idle rhapsody, not an aimless outpouring of vain imaginings, but a hard-working, extremely important cultural force.” Yet it wasn’t until around the middle of the 20th century that such scholars began to recognize the obvious corollary: that the work demanded of this cultural force does not simply vanish with modernity, and that there is nothing essentially ancient about myth. Philosopher Ernst Cassirer was perfectly happy with the idea that myths are still being produced, especially in the political sphere—he regarded Nazism as an instance. “In all critical moments of man’s social life,” he wrote, “the rational forces that resist the rise of the old mythical conceptions are no longer sure of themselves. In these moments the time for myth has come again.”

Still, for Cassirer, mythmaking remained an atavistic throwback, a strategy necessary only in “desperate situations.” It took a theologian to dismantle that idea: the German Rudolf Bultmann, who sought to “demythologize” the Christian New Testament. To seek historical verification of the scriptures or reconciliation of their account of cosmogenesis with science is not, he argued, a meaningful pursuit. Rather, their message is ethical and philosophical. It’s the same with all myth, he said: it expresses timeless human experience:

The real purpose of myth is not to present an objective picture of the world as it is, but to express man’s understanding of himself in the world in which he lives. Myth should be interpreted not cosmologically, but anthropologically, or better still, existentially.

If this is indeed at least a part of what myth is about, then myth-making can cease only when “the world in which we live” has ceased to change, and when we have solved all of our problems and resolved all of our anxieties. That, I suspect we can agree, will not be any time soon.

___________________________________

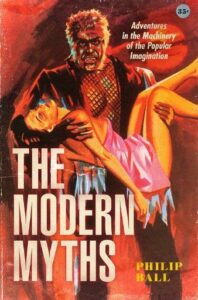

Reprinted with permission from The Modern Myths: Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular Imagination by Philip Ball, published by The University of Chicago Press. © 2021 by Philip Ball. All rights reserved.

Philip Ball

Philip Ball is a freelance writer and broadcaster whose many books on the interactions of the sciences, the arts, and the wider culture include H2O: A Biography of Water, Bright Earth: The Invention of Color, The Music Instinct, Curiosity: How Science Became Interested in Everything, and, most recently, How to Grow a Human: Adventures in How We Are Made and Who We Are. His book Critical Mass won the 2005 Aventis Prize for Science Books. Ball is also a presenter of Science Stories, the BBC Radio 4 series on the history of science. He trained as a chemist at the University of Oxford and as a physicist at the University of Bristol, and was an editor at Nature for more than twenty years. He lives in London.