Why Are So Many Mexican Novels Set in Cantinas?

Nicolás Medina Mora Considers the Role of the Neighborhood Watering Hole in Mexican Literature and Culture

Some decades ago, when Mexico was still ruled by an authoritarian regime, one or another president remarked that the only two establishments one could be sure to find in every town in the country, no matter how small or remote, were a Catholic parish and an outpost of the state-owned store that sold subsidized milk. But he forgot to mention that most important of Mexican institutions, one so essential to the wellbeing of the nation that, if it disappeared overnight, the fatherland might well sink into the sea. I’m talking, of course, about the cantina.

In the most general definition of the term, a cantina is an establishment that sells booze—and often, but not always, food—to be consumed on the premises. But the particulars vary widely across geography and class lines. A few are downright fancy, with waiters in bow ties serving steak tartare. Many are little more than a tin roof, half dozen Corona-branded plastic tables, and a beer cooler powered by a diesel generator. Most are unpretentious neighborhood joints where you go with colleagues after work or to watch a soccer game with friends.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Mexican literature is to a great extent a literature of the cantina.Yet to think of cantinas as analogous to American bars would be as silly as conflating them with German biergartens. If in the United States the archetypical dive is a darkened room outfitted with a jukebox and a pool table, where patrons sit on stools and order from the barkeep, the ür-cantina is a large hall, bright with the glow of unforgiving fluorescent lights, where drinkers play dominoes and listen to buskers who play for tips while waiters ferry rounds of mezcal.

These differences reflect a distinction beyond the realm of aesthetics. Cantinas and bars both sell alcohol, but few among their clients come to them in search of just a drink. Many American bars, for instance, offer another, more elusive intoxication: the tantalizing possibility of going home with a stranger. Hence the dim lights and loud music: by making it hard to see and hear one another, they make it easier for drinkers to convince themselves that the person on the next stool is interesting and attractive.

By contrast, most cantinas forbade entry to women until a few decades ago. Such belated gender integration helps explain the atmosphere: if you’re a man meeting his man-friends to talk about man-things (and also, as so many of the ballads of the cantina repertoire make all but explicit, to be a man looking at other men with aching and barely suppressed desire), you want to be able to see who is sitting across the table.

All of that is changing. The poet Luis Miguel Aguilar recently told me that in the 1990s the clientele at El Centenario—the cantina in Mexico City where my friends and I used to drink in the 2010s—consisted of “amateur boxers and retired taxi drivers” who would have been rather annoyed by our artists-and-editors set. But, of course, what goes around comes around. In 2018, when I moved back to Mexico City after a decade in the United States, I was aghast to discover that the joint had been overrun by hoards of Gen Z barbarians whose brains had yet to finish developing. How else to explain that they would think it a good idea to expel the elderly balladeers who’d struck me as so delightfully quaint in my oh-so-distant youth to make way for a norteño ensemble of out-of-tune brass and eardrum-busting snares?

Nothing in this evolution is surprising: there are few places where the drip-by-drip mutations that transform a culture over the course of centuries are more plainly visible at the scale of a human lifespan than the places where people gather to eat and drink outside their homes. More importantly, many of the changes that cantinas have undergone in recent decades are positive: today, unlike in the time of the boxers and the cabbies, the crowd at El Centenario approaches gender parity.

One thing, however, has remained the same: cantinas are above all places for conversation. The fascinating corollary is that this also makes them exceptionally useful for writers of literature. Hence why so many novels about Mexico feature scenes set in cantinas. To preempt accusations of nationalism, let me name two examples from authors that weren’t even Mexican. In Under the Volcano, Malcolm Lowry takes free indirect style to delirious new heights to drown the reader in the hallucinatory sensations of a British diplomat who has spent the last few years drinking himself to death at a working-class cantina in a town not far from Mexico City. In The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolaño repeatedly sends his would-be poets to La Encrucijada Veracruzana, a cantina based on a real-life establishment on Calle Bucarelí, where they talk shit about Octavio Paz—and in the process reveal themselves to the reader.

But it may well be that the greatest cantina-novel of our time is Hurricane Season, Fernanda Melchor’s Faulknerian epic about the femicide of a transgender witch from a small town in Mexico’s Gulf Coast. When I paged through it just now, I counted nineteen instances of the word “cantina,” an average of one for every twelve pages of the Spanish edition. In Melchor’s novel, the cantina is an essential part of the life of the town where the plot takes place: as the narrator says of one of the characters, it “is the closest thing to a home” for many of the residents of the village. The comfort of lukewarm beer, cheap food, and live music palliates the economic anxiety and the spiritual emptiness of a time and place where accelerated changes—the rise of the oil industry, the growing power of organized crime—are destroying the network of social relations that made poverty a little more bearable.

The reason why bars and cantinas feature heavily in both Mexican and American novels is that, actually, they’re the same thing.Yet Melchor’s ode to the cantina has a darker side that has to do with its oldest social function: a place where men could talk away from women. The misogynists at the center of the novel begin to plot the robbery that results in the murder of the Witch, whom they wrongly believe to be in possession of a treasure that could fund their escape from their ghastly town, at a cantina “where the crab empanadas that came with your drinks were stale and greasy but the beer was ice-cold and the sound of the music calmed [them] down.” Consider a passage in Sophie Hughes masterful translation:

What do you say? he’d ask Luismi when they went out to smoke a joint in the yard at the back of El Metedero. Suddenly, who knows from where, he’d had an idea for how to get the money, the thirty-thousand pesos: off the Witch…you know what they say, Luismi, they say she’s got gold in there, old coins worth a fortune…

Melchor—who, like Lowry, is a master of the free indirect style—allows her narrator to inhabit the minds of the characters for a moment: the future killer doesn’t know where the idea to rob the Witch came from. By this point in the novel, however, the reader knows the answer. The plan to assault her is the product of hundreds of nights spent at the cantina, a place where these men feel they can give free rein to their machismo, almost as if competing to see who can hate women the most.

What’s true of Melchor’s novel can also be said of many others. It doesn’t matter whether the characters are drunk on joy or sorrow or hatred; whether they are talking to themselves, bitching about rival poets, or plotting a home invasion or a revolution. In every case, the atmosphere of these peculiarly Mexican watering holes induces in them an emotional state of exception that leads them to speak their mind. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Mexican literature is to a great extent a literature of the cantina.

That, at least, was what I had in mind when I decided to include a long sequence set at El Centenario in my first novel. I began writing it at the end of my time in the United States: the years of anxiety when I watched my immigration prospects vanish under Donald Trump. By that point I’d been gone from my country for so long that I didn’t feel especially Mexican—but then the Department of Homeland Security informed me that, when it really mattered, I was defined not by my feelings but by the color of my passport.

My book, which I had originally conceived as a long essay about the Mexico City elite, became a way to think through my newfound awareness of everything that set me apart from my American friends. By insisting that cantinas were nothing like bars, I hoped to recast those differences as the product of my choice to be Mexican, rather than of the US government’s determination that I wasn’t worthy of becoming American. I was writing a book in English, sure, but the fact that so much of it took place at El Centenario irrevocably marked it as a Mexican novel.

In the years since I returned to Mexico City, however, I’ve come to see that the differences that I felt so acutely back then aren’t quite so stark. This change of heart, it’s true, amounts to acknowledging the obvious: Just as people flirt in cantinas every bit as much as they do in bars, some of the best conversations of my life have taken place in dives north of the border. I’ve even begun to wonder whether the fact that American fiction is full of scenes set in watering holes means that we can’t really speak of a clear distinction between the literatures of Mexico and the United States. After all, Hurricane Season owes a great deal to The Sound and the Fury—and Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station is a homage to The Savage Detectives.

And so I’d like to end by admitting that the premise of this essay is false. The reason why bars and cantinas feature heavily in both Mexican and American novels is that, actually, they’re the same thing.

__________________________________

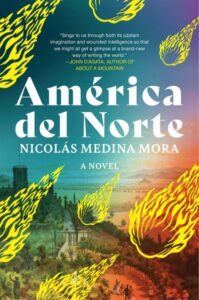

América del Norte by Nicolás Medina Mora is available from Soho Press.

Featured image: Juan Carlos Fonseca Mata used under license of Creative Commons 4.0.