Why are so many adults still obsessed with Busytown?

Image from richardscarry.com

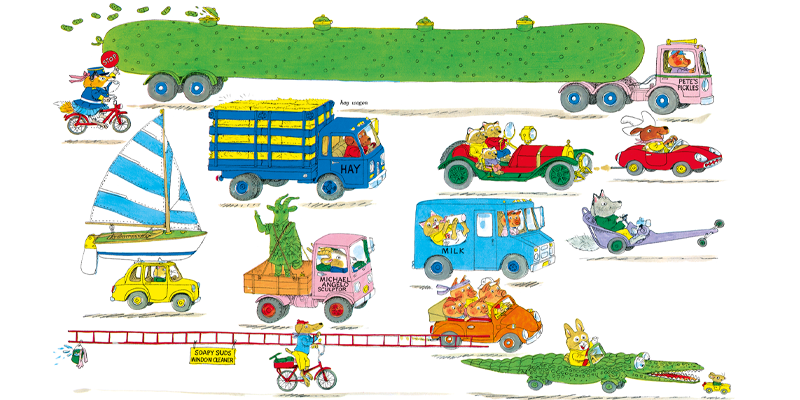

Today would have been Richard Scarry’s 105th birthday, and it got me thinking about Busytown, the world created by Scarry and explored in dozens of books. Scarry’s busy world is populated with animals doing the work of humans, explored across page after densely illustrated, brightly colored page. The animals go about their days as humans do, accompanied by simple descriptions of their jobs or what they’re up to—A fox flies a plane (“Pilot”) and a pig lays some bricks (“Jason started to build the chimney”).

Scarry’s Busytown books seem to be a long-winded answer to the question posed by his 1968 book title, What Do People Do All Day? The answer is, well, they’re busy. Scarry’s many books are dense with animals, jobs, and activities, and seem to mostly evade plot. The Times describes it as “not following a story so much as hanging out in a world. ‘Look,’ these books say, ‘there’s this and there’s this, and over here there’s this.’”

This invitation to explore is one of the reasons why the books are so captivating, but why is it always on my social media feed? Why are so many adults still obsessed with Busytown?

The basic appeal seems to be that it’s always fun to see a little guy go about her day. Looking at animals in little outfits working as carpenters and helicopter pilots satisfies a deep-set human craving for a cuter world. And since Scarry’s books are so wide-ranging, he’s illustrated a little guy that’s perfect for every occasion.

Take Busytown’s viral star, Lowly Worm. He’s the worm in a green hat and a single shoe who drives an apple around, and he’s immensely popular online. He popped up when Apple announced a car a few years ago and more recently when RFK Jr.—the top presidential candidate among America’s male cousins—announced he had brain worms. Lowly Worm speaks to the gay experience. Lowly Worm is the perfect driver for both the Fast & Furious and Mad Max franchises. Lowly Worm is both a lover and a partner. Lowly Worm is the ideal Little Guy With Somewhere To Go, which is something the internet will always cheer.

Busytown also seems to be an enviable place to live. To me, the civic appeal of Busytown is that Scarry depicts a town that works, to borrow a phrase from The Simpsons. Busytown is what certain jealous Americans imagine more socialist European countries are like: bustling and jovial. Everyone has a job to do and takes to it with a smile, and the unfortunate woes of life are tended to diligently and effectively. It’s especially appealing in the face of a more venial and exploitative reality, closer to Ruben Bolling’s satirical, 21st-century Busytown. “I wish I lived in Busytown” is the progressive Twitter addict’s equivalent of the centrist’s “If only our politics were more like The West Wing!”

Of course, Busytown is a fantasy and far from perfect itself. There’s a lot of very fair criticisms to be leveled at Scarry’s world, including for its rigid depictions of traditional gender roles and some racially insensitive depictions.

The critiques range into the highly academic too, including this extremely dense academic paper on labor and class in Busyworld which counts, sorts, and analyzes all the jobs and animals in What Do People Do All Day? The paper includes lines like, “From the raccoon jobs we come to the major category of GREATER PIG, which could be called without too much error ‘America’s Working Man’ (with all the connotations of the particular consciousness uncovered by Halle, 1984).”

The essay claims that Scarry’s books are warping children’s perceptions of “class bodies and the logic of social structure” with things like showing that pigs are causing the most accidents:

Fully 16% of the pigs are involved in a mishap of some other, far more than any other species, and unlike the other species, they are the cause of the mishap 75% of the time, as opposed to the innocent victim. Less than 2% of the other animals, in contrast, are the cause of a mishap. But pigs fall into bread dough, they fall into rivers, toss pancakes out of windows. The main pig character (‘Daddy Pig’) stuffs himself with food, getting so heavy he breaks his children’s beds – they move into Mommy Pig’s bed, while he lies snoring obliviously.

To be frank, I don’t think I’m smart enough to untangle and evaluate the claims being made here, but I bring it up mostly to say that like the terminally online, academic sociologists are also obsessed with Busyworld.

In any context, though, if you grew up with Scarry’s books, it’s nice to bump into the old pals like Lowly Worm again as an adult. Incidentally, Lowly Worm was one of Scarry’s favorites too, and as one of his obituaries quotes, “he believed that young readers like to see familiar characters recur in books, just like they ‘like to see their familiar friends again and again—like in real life.’”

No doubt this is one of the core appeals of Busyworld. Beyond its quietly efficient, perhaps overly normative depictions of little guys at work and at play, the things that fascinated us as kids have a way of wriggling in and driving us around long after we’ve grown up.

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.