Why a Small-Town Record Store in Rural Pennsylvania Was My First Library

Jolene McIlwain on Rural America, Songwriting, and Oral Storytelling

At Gene’s Music City, albums covered in sagging plastic wrap lined three walls. Behind the counter 45s hung on a massive peg board and hundreds more LPs seemed to be waiting on the shelves, readying to be flipped through. Gene was a near-twin to Wolfman Jack, the well-known thick-haired, bearded disc jockey of the 70s, but Gene was quieter, more contemplative. He’d play a tune if you asked for a sample, handling the vinyl like blown glass.

Though my blue-collar family struggled between layoffs, we owned a stereo console cabinet with good solid speakers. We might not have been a reading family with shelves of books, but we had a modest yet amazing collection of records. We were a music family. I spent hours memorizing lyrics of my dad’s favorites, “Boy Named Sue” from Johnny Cash’s At San Quentin album, all of Hank William’s hits, Patsy Cline’s.

After I learned to read, I pored over liner notes, transcribing lyrics, gingerly lifting the needle to replay and replay until I got the words just right as this was important work, learning this kind of storytelling. I knew it then, and in countless ways I’m sure of it now.

Neuroscientists and researchers, studying neural pathways with the help of music and MRIs, have proven that in adolescence, the effect of listening to music is particularly powerful: we are laying down the tracks along which we’ll respond to music for decades to come. So, bookstore owners, music store owners like Gene, and librarians hold the keys to powerful experiences for Americans who are cut off by geography.

Recent studies of rural communities and education have also shown that rural America, like urban America, is diverse in economics, race, and lifestyle, recognizing there are categories of rural—“fringe,” “distant,” and “remote”—with unique needs. Librarians are doing their best to clarify the specific needs of those in rural America and then developing ways to meet them despite lack of funding and support, but there is still much to improve.

The effect of listening to music is particularly powerful: we are laying down the tracks along which we’ll respond to music for decades to come.

Like many young kids in urban settings, those from my rural western Pennsylvania community had limited library exposure; some of us never stepped foot in a real library until junior high. Elementary schools shared a traveling librarian who’d cart books in her car. A bookmobile showed up each month, depending on the weather, but it’s nearly impossible to learn the art of browsing stacks when others are waiting for their turns, when there’s no lingering allowed. And those who lived too far out didn’t have access to free public library cards; only kids in town did. Instead, it was music that made me a writer.

Through songs, I built my lexicon as well as my early story craft. Back then, I hadn’t yet heard of so-called “high” and “low” art, of pop culture and the cultured elite; back then, no one knew Dylan would win the Nobel or they would teach his lyrics at the Ivys. I just knew that with one Carly Simon song, I not only learned the meanings of “vain,” “yacht,” “gavotte,” “eclipse,” “naïve,” “lear jet,” I found, on our spinning globe, the Saratoga and Nova Scotia she mentioned in “You’re So Vain.” And I was obsessed.

I can’t remember many paragraphs from books I’ve loved, ones I’ve read and taught time and time again. I may not have been able to memorize lines from the Canterbury Tales or The Declaration of Independence or Poe’s “Annabelle Lee,” but I still remember the entirety of “Devil Went Down to Georgia” and “Hotel California.” Songs like The Eagles’s “Hotel California” taught me the effectiveness of place, concrete detail, metaphor. Was the hotel actually Hell? What is that “warm smell of colitas” and what are those “mission bells”? My siblings, my friends, and I deconstructed the lyrics together, making attempts at meaning. Sometimes I’d go for days wondering … It was my first taste of literary analysis, of understanding the elements of story. This curiosity led to my first desire to write my own stories.

I studied pathos in songs—didn’t have the word for it until I was in college, but I could feel it. I wanted to learn how to bring on that aching like Elvis singing “Old Shep,” Michael Jackson singing “Ben,” (from the movie of the same name—good gravy, a young musician with a rat as his pet, and yes, spoiler alert, in the movie the rat dies), and Henry Gross singing “Shannon” written about Beach Boy Brian Wilson’s dead dog (Yes, I had a thing for songs written about dying animals, still do!).

The legends I learned about through songs were also endlessly compelling—some from real life (Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”) and some entirely fictional (Bobby Gentry’s “The Ode to Billie Joe”). Also, many “legend” songs had twist endings and I’d studied them long before I knew of O’Henry. Vickie Lawrence sang the ever-confusing “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia” with an ending that Tarantino’s characters discuss in the opening scene of Reservoir Dogs.

Powerful endings were another element I learned from songs like “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” which reveals in the end that the man stopped loving his former lover “today” only because he is dead! It was one of my dad’s favorites and I remember Dad whispering, just before the last verse began, “Here’s the kicker, listen.”

Songs, like books would later do, gave me an opportunity to walk into worlds I wasn’t allowed to venture into.

I’d overhear Gene mentioning how he was “digging” the bridge in a song. And once I learned what he meant, well, yes! movements into the bridges (as in Springsteen’s “Born to Run”) or choruses (James Taylor’s “Fire and Rain”) highlighted these concepts so well that I could easily recognize this same work in non-songwriting.

Meatloaf’s “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” and Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” give us the elements of mosaic writing, contrasting styles of story telling, and the infinite power of juxtaposition I would later cherish in literature, such as Elizabeth Wetmore’s Valentine and George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo.

Songwriters know their audience, and writers must, too. Some songs make the listeners do the hard work of translation with their oblique references: Was “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” code for LSD? I so badly wanted to ask Gene. He’d know. I always eavesdropped on his conversations listening for these small details, keeping my eyes on the albums and not on the Day-glo blacklight posters of cobras that led to the back room because I was warned by friends that if I stared at them too long I might get high. There was so much to learn, and songs, like books would later do, gave me an opportunity to walk into worlds I wasn’t allowed to venture into, worlds of sex and drugs and worlds beyond my working class life.

Words from artists’ native languages found their way into my house, and my dad, the son of an Italian immigrant, loved songs that bridged these worlds. I can’t hear Don Ho singing “Tiny Bubbles” without hearing my dad’s deep baritone voice attempting to sing those Hawaiian words. My mom sang “Que Sera, Sera” just like Doris Day, and we kids sang ABBA’s “Chiquitita.” Rod Stewart’s “Georgie Boy,” introduced me to the reality of violence against the gay community. Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman,” led to discussions about female empowerment. Dolly Parton’s message in “Coat of Many Colors” taught me that the shame attached to being poor can be overcome if we just learn how to celebrate our vast creativity.

These songs taught lessons I couldn’t have learned as effectively in a formal school setting. Words from a textbook or lecture wouldn’t necessarily stick like those in the strong voices of Stewart, Parton, and Reddy. As a teenager, The Eagles’s “The Last Resort” led me to seek out more information about how not just my own state of Pennsylvania was affected by industry, development, greed—what I would later learn was the concept of manifest destiny—but about how many more places were affected similarly. I remember sitting in the living room listening to the skip, skip, skip at the record’s end, lifting the needle and playing it again—the delicate piano notes in the middle maybe symbolizing how delicate our Earth is.

Kids like me are still held back, still internalizing the message that the way they’ve come to stories is not up to par with the way it should be done. You won’t find the stories my neighbors tell in the literary canon. By certain measures, it could seem we were limited by place, by culture, by language, by economics.

When ABBA’s Mamma Mia hit the broadway stage in 2001, there was no way I could afford to see it. But I try to remember that we always had music on the radio and we had Gene’s Music City, and when I write my stories I work to honor those artists who taught me pacing, character development, pathos, sense of place, by including the titles of their songs in my tales every chance I get. I may not name-drop Shakespeare and Dostoevsky but you’ll definitely see the names of singer-songwriters and their beautiful work.

When I met the boy who would become my future husband, we sat in his mom and dad’s old Buick Skylark, in the middle of the western Pennsylvania woods, looking out for red fox and whitetails, watching the snow fall on the windshield, hoping the tires would get us home safely on the dirt roads, and we listened to Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” and Rush’s “The Trees” and an honest-to-goodness love story was born. I’d found yet another person in this small town who’d analyze songs with me.

_____________________________

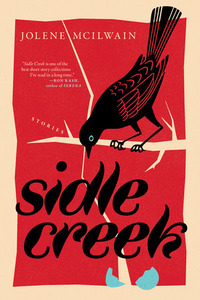

Jolene McIlwain is the author of Sidle Creek, available now from Melville House.

Jolene McIlwain

Jolene McIlwain’s fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and appears in West Branch, Florida Review, Cincinnati Review, New Orleans Review, Northern Appalachia Review, and 2019's Best Small Fictions Anthology. Her work was named finalist for 2018’s Best of the Net, Glimmer Train’s and River Styx’s contests, and semifinalist in Nimrod’s Katherine Anne Porter Prize and two American Short Fiction's contests.