Why 1997 Was a Pivotal Year in the Life of George Michael

Princess Diana’s Death, Ellen, and the Fear of Coming Out

George Michael’s friendship with Princess Diana had been sporadic, limited mostly to occasional lunches—some with Elton John at Kensington Palace—and the odd phone call. She had touched him with a consoling call after the death of his mother. But Michael sensed a lonely woman. If his stardom and wealth had made it hard for him to form honest relationships, for Diana it was almost impossible. A doctor of hers, Michael Skipwith, described the princess in terms to which Michael could relate: “All she wanted was to be treated like other people, and for those she trusted not to talk about her.”

On August 31, 1997, Michael and the rest of the world heard the shocking news. Just past the stroke of midnight, a chauffeur-driven car had sped through a tunnel in Paris; it held the former Princess of Wales; her bodyguard, Trevor Rees-Jones; and her new boyfriend, Emad “Dodi” Fayed. A battalion of paparazzi had trailed them in cars and on scooters. The driver, Henri Paul, lost control of the car, which crashed; an autopsy revealed that he had been driving under the influence of alcohol and prescription drugs. Only Diana’s bodyguard survived. Among her last murmured words as photographers with cameras surrounded the totaled car: “Leave me alone.”

Instantly a feeding frenzy began, with “intimates” selling stories to tabloids: hairdressers, a medium, a masseur. The situation, over time, would play itself out again with Michael. For him, the circumstances of Diana’s life and death hit unnervingly close to home. The whole episode was a reminder of the brittleness of the fame he’d achieved and that still obsessed him. At its heart was his assumed heterosexuality. Michael argued repeatedly that he had shared the truth with everyone that mattered to him, but that was a small group, and did not even include his band members. Singer-songwriter Toby Bourke recalled Michael’s “deep-seated paranoia”: “He was terrified his big secret was going to come out.”

The late nineties remained a risky time for celebrities to come out.

It was already such a rampant rumor that it threatened to overshadow his music. But the more reporters asked, the more stubbornly he withheld. “If there’s one question I know is gonna come up it’s that,” he told an interviewer. “You can almost see people sitting there waiting for a moment to throw the question in—where’s it gonna be received best?”

Asked by writer Richard Smith what he would do if he were outed, Michael lost his cool. “I can sue them but they’ll still have ruined my career. . . . Once something’s printed the damage is done. Who fucking believed Michael Jackson when he said he wasn’t gay? . . . Because I don’t make my sex life public, there’s a section of Fleet Street who are desperate to know who I’m fucking. They’re certainly not going to find out.” To the Daily Telegraph’s Tom Leonard, Michael seemed “desperate to be candid, but at the last minute [he] can’t be.”

He wasn’t alone. The late nineties remained a risky time for celebrities to come out. Managers, agents, and others on the payroll discouraged it, warning that it would spell career death. Many stars longed to do so, but were afraid. They faced mounting pressure from gay activists to come clean; those who refused were scorned as traitors to the cause or were outed in print.

By 1997, TV star Ellen DeGeneres could no longer ignore an insistent chorus of demands that she come clean about her sexuality, which had passed the stage of rumor. The droll comedienne with the blonde crewcut had a lot at stake: She had fought her way up from years of doing standup to star in a long-running sitcom, Ellen. She wanted out of the closet, but she was scared: “Would I still be famous, would they still love me if they knew I was gay?”

Rather than utter the words that people wanted to hear, she dropped hints, which only served to frustrate the gay media. Finally, she orchestrated a double-barreled coming out. After months of arguments between her and ABC, it was decided that her character would come out to a therapist, played by Oprah Winfrey, on April 30. With that established, Time put DeGeneres’s face on its cover, accompanied by the headline, “Yep, I’m Gay.” The placement proved what explosive news this was in 1997.

The episode scored Ellen its biggest audience ever—forty-two million viewers. Now out with a vengeance, DeGeneres shifted her show’s focus to LGBT themes. Then the fallout came: JC Penney and Chrysler pulled their ads; televangelist and Moral Majority cofounder Jerry Falwell christened the star Ellen DeGenerate. The Media Research Center, a powerful conservative watchdog group, took out a full-page ad in Variety declaring that ABC was “promoting homosexuality.”

Buckling to pressure, the network placed viewer-discretion warnings at the start of her episodes. DeGeneres was stung by Elton John’s remark that she should ease up on the gayness and go back to being funny. When she put her arm around girlfriend Anne Heche at a White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, the New York Times noted her “ostentatious display of affection with her lover.”

In 1998, Ellen was canceled. It took years for the star’s career to bounce back. Months after the show’s demise, she saw Will & Grace—a sitcom about a female interior decorator and her funny, nonthreatening gay pal—premiere on NBC and zoom its way to a ten-season run.

Michael had been in the closet for far longer than DeGeneres; the more pressure he felt to come out and the more open his secret became, the more he resisted. Yet in interviews, it was often he who broached the subject defensively, evasively, yet with a burning desire to somehow come clean. In the discussion that opened “An Audience with George Michael,” his live BBC concert, the singer said to host Chris Evans: “Everyone presumes I don’t do interviews ‘cause I’ve got loads of things I don’t want to talk about, which is not the truth at all.”

“People are obsessed with your sexuality, aren’t they?” asked Evans.

Michael spent minutes analyzing the issue. All this badgering, he insisted, grew out of homophobia. Most straights, he explained, were so insecure about their sexuality that they rushed to “out” those whom they perceived as gay. “And that’s why you get a huge debate over somebody like me,” he declared. “Because you’ve got all these guys, for instance, maybe their girlfriend likes me or whatever. And they’re like, he’s a fairy! It’s obvious to me! Now if they were proved to be wrong, that would be unsettling for them. If they were proved to be right, that would be comforting.”

But as always in interviews, Michael withheld. “All the people that I know and care about are perfectly clued in. Everybody knows who I am. So, for the sake of people that I never speak to, I really don’t feel any desire to define myself.”

As ever, Boy George was there to point out the irony of Michael’s words. “George says he has nothing to hide and that he has never considered his mysterious sexuality to be wrong,” he told the Daily Express. “If that’s the case, then why can’t he get it past his lips? Is it really that awful?”

__________________________________

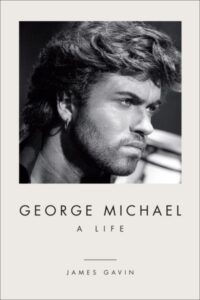

Excerpt adapted from the new book George Michael: A Life by James Gavin, published by Abrams Press © 2022.

James Gavin

James Gavin is a writer and music biographer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Time Out New York, and Vanity Fair. He is the author of Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker, Is That All There Is?: The Strange Life of Peggy Lee, and Stormy Weather: The Life of Lena Horne. He lives in New York City.