Whose Idea of America? Rauschenberg, Whitman, or Trump?

Geoff Hilsabeck Considers a Country at War, and the Artists Within

I spent several hours last weekend walking through the crowded galleries of the Robert Rauschenberg retrospective now up at MOMA and titled “Among Friends.” I had driven more than six hours to encounter this work, which I have always loved but only ever seen in books, from the town in West Virginia where I live to New York City. I consider New York our nation’s true capital, the spiritual center of both American democracy and American capitalism, home to both Walt Whitman and Donald Trump.

Indeed, Donald Trump was on my mind as I made my way through the museum, and more so than usual. That morning I had read that the Trump Organization, now run by Eric and Donald Jr., is opening a chain of mid-market hotels called “American Idea.” They will be clustered in the south, Trump Country, with the first locations in the Mississippi Delta. Less about building than rebranding, the American Idea hotels will outfit old Holiday Inns and Comfort Inns with antique Coke machines and Sinclair gas station signs—“flea market chic,” says Trump Hotels CEO Eric Danziger—and sprinkle them with Trump dust. “It’s about small-town America,” Danziger says. This was the America that 7 out of 10 Trump voters had in mind when, after casting their ballot for him, they told pollsters that life was better in the 1950s—more prosperous, I suppose, more familiar, more white.

The idea came to the Trumps while driving across the country campaigning for their father. “We saw so many places and so many towns and heard so many stories,” says Donald Trump Jr. It was a real “crash course in America.” What doesn’t seem to have been covered in that course, however—what is conspicuously absent from Trump’s American Idea—is democracy. The president and his sons have no feel for, no interest in democracy. After all, democracy requires what the philosopher Jürgen Habermas calls “domination-free communication.” In a democracy, says Habermas, people use dialogue to work toward emancipation and solidarity. But for Trump and his sons these words—dialogue, emancipation, solidarity—are antiques. They reek of the 19th century, and the Trumps belong to the 21st century, which, they claim, is thoroughly, unabashedly capitalist, all barely disguised rage and bottomless want. They strive to dominate the competition, be it Hillary Clinton, the media, or truth itself. In their world, social relations are essentially transactional and all about winning, no matter the costs.

Here, though, in Rauschenberg’s splashy canvases and goofy sculptures, in his assemblages, prints, recordings, and installations, was the American Idea less cynically expressed, more hopefully embodied. As soon as I stepped into the show, which opens with two prints he made with—and of—Susan Weil when they were in their twenties and living together in Paris and continues from there to a long black tire print he did with John Cage and some painted screens he constructed for Merce Cunningham, I felt myself in another, brighter country, a place of spontaneity and participation. Freedom and equality—the free exercise of thought, a radical absence of hierarchy—were the guiding spirits.

*

Robert Rauschenberg grew up in Texas on the Gulf Coast in an oil town where his father was a grunt and then a lineman for the power company. He wore high-laced lineman’s boots (which show up here and there in the artist’s work). There was no money. Rauschenberg liked to draw; his father liked to hunt and fish. Rauschenberg dropped out of college and was drafted, but he refused to kill people, so they placed him in a TB ward to wash and dress corpses. They sent him to a neuropsychiatric center. Like Walt Whitman he nursed GIs who had been maimed and crippled and who had lost their minds. When the war ended he went back to his hometown but his family had moved away and hadn’t told him. People like to say he was very American, was fascinated by space travel, liked big things, kept the TV on all day.

After the war he moved from Texas to Paris and met Susan Weil. They left Paris together and went to New York to enroll in the Art Students League and then south to Black Mountain College in North Carolina for the 1948-49 academic year. There Rauschenberg encountered Josef Albers, his most important teacher. Albers had left Germany and the Bauhaus with his Jewish wife, Anni, to join the faculty at the small, experimental college. He was part of an exodus from Germany and France of intellectuals and artists, many of whom, including Hans Hoffman (who introduced Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock’s wife, to the drip method) and Arnold Schoenberg (one of John Cage’s earliest teachers), played major roles in shaping postwar American art. Albers wore a lab coat and white gloves to class. His task, he said, was to open eyes. He assigned his students projects using everyday materials like broken glass, cardboard, cigarette butts, bark and leaves and moss. Rauschenberg, who worked in trash collection—all the students at Black Mountain had to work—took well to this instruction, but Albers chafed at the young artist’s sense of free play, his messy permissiveness. As Rauschenberg put it in his text-image piece “Autobiography,” he “worked hard but poorly for Albers.”

Rauschenberg and Weil went back to New York in the fall of ’49 and were married the following summer, but they separated after a year, not long after the birth of their son, Christopher. He traveled to Europe with Cy Twombly from the fall of ’53 to the spring of ‘54, and when he came back to New York he met Jasper Johns. Johns was seeing a woman named Rachel Rosenthal at the time, an artist, and even after they broke up they continued living together at 278 Pearl Street in lower Manhattan. Rauschenberg lived just down the street. They all lived in condemned lofts where they worked and slept. Rachel Rosenthal had a tub where they bathed. When she moved to California Rauschenberg took over her loft on the top floor. Johns was one floor below him. There they lived and worked for the next five years, broke and obscure. They fell in love. Nobody knows much about their relationship, what it meant, why it ended. Johns never spoke of it, and Rauschenberg did only occasionally. They were lovers, friends, collaborators. “I’m not afraid of the affection that Jasper and I had,” he said. They gave each other permission—that’s how Rauschenberg put it.

Every night the two men sat in a booth at the Cedar Bar with John Cage and Merce Cunningham talking about their work and their days, which were becoming the same thing. They talked about making art based on ordinary perceptions and experiences. At the next table Jackson Pollock and Bill de Kooning were still immersed in the dream, the dark wood, the deep interior. Rauschenberg famously said that he tried to act in the gap between art and life. He also acted in the gap between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, the heat of the one and the cool of the other. He came of age as an artist when Abstract Expressionism had outlived its usefulness, and Pop Art had not yet hardened into postmodern orthodoxy. At the Cedar Bar, after talking to Cage for a few hours about chance and ordinariness, he and Johns would walk home through the canyons of Soho and the warrens of Chinatown to Bartleby’s lower Manhattan streets. There, they would often work all night, Johns on his targets, Rauschenberg on what he called his “combines,” since they combined elements of painting and sculpture.

*

It was the combines—messy, fast, somehow both ugly (uglier than I had imagined) and beautiful—that I had come all the way to New York to see. “Short Circuit,” with its two wooden doors taking up the top half of the canvas, behind which sit paintings by Weil and Johns, which Rauschenberg included after his painting had been accepted to a show but theirs had not. “Rebus” a large canvas nearly as tall as me and with as wide a wingspan. Images of different sizes, many of them scrubbed or painted out of intelligibility, scroll left to right across the center of the picture plane like a spine: a campaign poster for a lieutenant governor’s race; a runner at a track meet; comic strips; a small reproduction of the Birth of Venus. Paint and patterned fabric are slapped on here and there, swathes of cool yellow, dark brown, unmixed white that appears to have come straight from the tube.

Rauschenberg had no sense of color or of composition either. The eye jumps from place to place with what the critic Andrew Forge called “a larklike mobility.” But Rauschenberg didn’t seem to care about composition or color. He wasn’t after beauty. His is a democratic canvas where everything is equal, every color, every material (newspaper, political poster, fabric, an old shirt, a sock, a paint tube, scrap metal, taxidermy), every type of image (drawings by Cy Twombly and by his son Christopher, comic strips, prints of famous artworks, postcards of buildings and cows and presidents, Judy Garland’s autograph). This pursuit of radical egalitarianism—unwilling to privilege one thing over another, uninterested in hierarchies—started when Rauschenberg was studying at Black Mountain with Josef Albers and reached its fulfillment ten years later in his Pearl Street studio, with Jasper Johns looking on or upstairs pasting newspaper on a canvas before painting a target on top of it.

The democratization of materials that Albers had taught mixed with Rauschenberg’s native sense of play and his impatience with boundaries to push the art off the canvas and into space. This is nowhere more true than in “Monogram,” the most famous and misunderstood of the combines. In it, a stuffed goat (frustratingly trapped in glass at the show) stands on a square pasture of painted boards with a tire around its middle. Its nose is painted red, green, and white. Theories abound as to the significance of the encircled goat, but it struck me when I finally saw it in person as being simply the expression of a lesson Albers had taught Rauschenberg ten years earlier about juxtaposing textures, in this case the rough fur of the goat and the rubber tread of the tire.

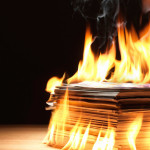

While “Monogram” is the most famous of the combines, “Canyon” is, in my opinion, the best. At the bottom, perched on a small cardboard box, is a stuffed eagle with its wings spread wide, the whole bird painted black, an ominous figure that seems to hold the weightless freight of every soul we have ever separated from its body in our endless wars. The box on which the bird stands is attached to a wooden beam, from which hangs, absurdly, a small, striped pillow half a foot below the canvas. Above the bird is a cluster of overlapping and faded signs. Fragments of the words association, labor, and democracy are just barely visible. On the far side of the canvas rests a photograph of Rauschenberg’s baby son sitting naked in some leaves, his left arm reaching up to the sky. Elsewhere, amid the chaos of the surface, are a postcard of the Statue of Liberty, a flattened metal drum, patches of black, grey, and white paint. There is very little color, just some reds and blues blurring the words in the center.

It is hard not to see this combine as about America—of it, really: the eagle came from the trash of the last of Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders (a friend of Rauschenberg’s was living next door to him), the words were, presumably, from posters pasted to the side of a building. Its objects and images hold the reality to which we aspire and the reality in which we actually live, messy, hard, ineluctably violent. Rauschenberg levels the playing field between words, images, and objects, putting the infant and the eagle, for instance, on the same plane. The tension in “Canyon” and in every other combine is a fundamentally American one: can these diverse elements be brought together into a workable whole? “Danger and chaos—these are the real muses an artist must court,” he said.

*

Across the room from “Monogram” were 34 drawings that Rauschenberg made to illustrate Dante’s Inferno, one drawing for each canto. As I made my way through hell, I struck up a conversation with two men, old friends of each other, I gathered, who were standing next to me. I told them about how Rauschenberg had made the drawings, transferring images from magazines and newspapers onto paper by painting the image with lighter fluid then flipping it over and rubbing the back of it with the blunt end of a ballpoint pen. This got one of the men talking about an uncle of his. Every night the uncle would take the day’s paper into the bath with him, and more often than not, the man said, he would fall asleep. When he woke up and got out of the water he would see reflected in the mirror the day’s headlines printed in reverse on his torso.

Something about that strange image, the wet and, I imagined, lumpy body of the old man bearing the marks of American life—its tragic headlines—on his body (the better to see them?), reminded me of Walt Whitman. Of course, I thought to myself. Of course Whitman would materialize in a Rauschenberg retrospective. The two were kindred spirits, and their work has so much in common: its scale, its tendency toward litany (this and this and this too), the way it resists analysis and invites participation. A certain superficiality too: it’s all surface, has no secrets, no depths.

There are personal and perhaps irrelevant similarities between the two men, like the fact that both were gay or that they both spent formative years in military hospitals and saw firsthand the chaos that the American military leviathan leaves in its wake, our early and ongoing taste for violent conflict. Both felt powerful attachments to presidents, Whitman to Lincoln and Rauschenberg to Kennedy, hopeful figures, tutelary deities within the work. Moreover, critical reception of both artists has always been ambivalent. The opening sentence of Jed Perl’s article in the New York Review of Books about the Rauschenberg retrospective in a way says it all: “Robert Rauschenberg was a showman, a trickster, a shaman, and a charmer.” What he was not, apparently, was an artist, just as Whitman was not a poet to many of his contemporaries. But Whitman and Rauschenberg worked from deep down where the frontier feeling of disobedience lives. I’ll go my own way, they said, and they did, making an art of opened doors and erased borders.

In the opening paragraph of his long, rambling screed “Democratic Vistas,” Whitman sets the conditions necessary for America to achieve its promise. “1st, a large variety of character,” he writes, “and 2nd, full play for human nature to expand itself in numberless and even conflicting directions… an infinite number of currents and forces, and contributions, and temperatures, and cross purposes, whose ceaseless play of counterpart upon counterpart brings constant restoration and vitality.” Rauschenberg’s art, particularly the combines, strikes me as a fulfillment of this vision.

When I left the retrospective and the museum, Donald Trump was still on my mind, of course, but so were Walt Whitman and Robert Rauschenberg. My head was full of color, my body tense and eager. The Trump Organization and its gross appropriation of the American Idea coexisted now with Whitman’s “fervid and tremendous IDEA.” I checked my phone. The world was in pieces, and I had been invited to remake it.