Who Made Who? On the Creative Collaboration of Man Ray and Kiki de Montparnasse

Mark Braude Considers the Blurred Lines Between Object and Participant, Artist and Muse

Kiki de Montparnasse sits on the tapestry spread across the floor, its chessboard pattern splayed out like an invitation to a game. She pulls down the fabric wound around her hips so that some of it lies along the ridge of her thighs while the rest falls behind to reveal the summit of her backside. She tightens other fabric encircling the top of her head in a turban, leaving exposed a small wisp of hair.

After trying a few, they find the position that works, a simple configuration. Kiki faces away from the camera toward the dark wall, her head turned to profile, alert to the clean angles she creates, her chin held parallel to her shoulder, arms in front of her, or crossed against the coldness, or held outward, or resting on thighs or knees—whatever it takes to hold the desired posture.

The goal is to sit so that shot straight-on, she’ll look limbless, her lengthened back like marble soaked in light. Much as the Venus de Milo would have appeared to them when viewed from behind at the Louvre, her own drapery hanging halfway down her hips.

What looks like a game to outsiders can feel like a duel to its participants.Maybe Aphrodite isn’t the reference they reach for, if they’re reaching for one at all. Maybe with her ear’s ornament dangling like bait, they’re going for Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. Or with her favorite shawl fashioned into a turban, they mean to conjure some cheap orientalist fantasia, Kiki as odalisque attuned to the noisy intruder spying from the other side of her seraglio with his camera.

Or, anticipating the f-holes that will later be tattooed onto her back, maybe she channels the ancien régime criminal branded for her trespasses, her skin marked by de Sade’s pen as much as by the darkroom’s light.

They’re puzzling, those twinned f-holes, now so much better known than the body onto which they’ve been inscribed. By indicating the depth of a cello’s resonant chambers, those twinned f-holes, burned into the final print, mean to complete the illusion begun with the angling of Kiki’s torso: her double act as woman and instrument. But it’s a trick lacking polish or prestige. There’s no effort to fool.

The f-holes have been rendered too clearly superficial for that. Instead we’re being challenged to hold both their visual artifice (we know these markings don’t belong to that woman’s body) and their analogical effectiveness (but her body does look like a cello) in our heads at the same time. The whole operation falls apart unless the viewer chooses to see the depth in those resonant chambers.

They seem locked in their own private contest, sitter and photographer. In the confines of this frame, they might be playing with each other on terms that, if not equal, feel at least unstable, being negotiated as we watch, as though we’re glimpsing a moment of mutual pleasure not yet enjoyed, more delicious in the endlessness of its temptation than the act or its aftermath could ever be.

It’s a scene of promised happiness. Which makes it a defiantly postwar picture, forward-looking and death-denying. The one final word that, five years after the Armistice, still hung in the air of every room has somehow been kept from this one. It’s a picture of life.

Or the opposite: it’s a fantasist’s prelude to the inevitable disappointment of reality.

What looks like a game to outsiders can feel like a duel to its participants. Maybe Man Ray spoke plainly when he titled the finished print Le Violon d’Ingres. A former musician, the nineteenth-century painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres had a reputation for annoying his studio visitors by incessantly plinking on his violin, so that un violin d’Ingres came to function in French as hobbyhorse does in English.

With his title, Man Ray told us how he saw the picture’s unnamed woman and how he wanted us to see her, too: as a plaything to be strummed and passed along for the next viewer. By marking her body in the darkroom (with her foreknowledge or not, we don’t know) after she’d finished performing her role as model, did he not reduce Kiki to the mere canvas for those f-holes, the rough material from which he created his concept?

Maybe this is a picture of war after all. Maybe the picture has less to do with Man Ray’s connection to the lively, modern Kiki in front of him than it does with his admiration for the pompous, reactionary Ingres, long dead. The easy allure of a woman’s turned back caught in a private moment: Ingres was this trick’s master, from the subjects of The Half-Length Bather (1807) and The Valpincon Bather (1808), seated, naked save for some fabric round their heads, to their doppelgänger, showing up more than fifty years later holding a mandolin to provide the focal point at the center of the fleshy tangle of The Turkish Bath (1852–59), naked save for some fabric wound around her head and a patterned blanket covering her thigh. Man Ray would have seen The Valpincon Bather and The Turkish Bath at the Louvre.

We don’t know if Man Ray was alone in coming up with the picture’s concept, staging, or titling. It requires less effort to imagine the person holding the camera as the sole commander of a shoot. It’s the photographer who takes something from the sitter—her picture—even if he can’t make it without her.

“The very beautiful women who expose their tresses night and day to the fierce lights in Man Ray’s studio are certainly not aware that they are taking part in any kind of demonstration,” wrote André Breton in his essay “On Man Ray.” “How astonished they would be if I told them that they are participating for exactly the same reasons as a quartz gun, a bunch of keys, hoar-frost or fern!”

But Kiki was the more musical of the pair, as well as the performer. Maybe she thought of herself as the instrument and as its player. She might have felt the opposite of degraded when seeing the completed image. She might have seen it more as their duet than as his solo. Maybe she thought the solo was hers. Impossible now to decipher who did what on that day in the studio. There’s no instrument by which to gauge how much of the picture’s rough magic is owed to his camerawork and how much to her performance in front of the lens.

Can you take a photograph of great feeling about someone for whom you’re trying to feel nothing? If, after taking a photograph, a photographer alters and titles it in such a way that it reads as an attempt to dominate his model, do we, too, have to see her as submissive?

Would we have such an image if the two of them had never met and fallen into their particular dance? Man Ray might have tried to produce a similar image with someone else. Kiki might have found another portraitist to capture the energy she was putting out just then. We don’t know. All we have is this picture, the lone tangible record of a certain quickening in the space separating Kiki’s particular body from the camera manipulated by Man Ray’s particular hands, in that room in Paris, for that moment in 1924. That crackling space between them is why the picture still feels so alive and unsettling a century after its creation.

Le Violin d’Ingres appeared in public for the first time in the summer of 1924, occupying a full sheet in the thirteenth and final issue of the Surrealist magazine Littérature, where it would have been admired by a few dozen or hundred people before their attentions turned to the novelty of the next page.

Kiki appeared again in print that winter when Breton published the inaugural issue of La Révolution surréaliste, filled with the recounting of dreams and pseudo-scientific queries into suicide. Inside, an advertisement for the newly opened Bureau of Surrealist Research invited any interested research subjects to visit 15, rue de Grenelle, where they would have seen a mannequin hanging from the ceiling, an altarpiece made up of copies of the Fantômas books and Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams surrounded by metal spoons, and a willing listener at a desk waiting to record their secret thoughts and fantasies or, if preferred, to lecture them on Surrealism.

A few pages later, wrapped in a full page of text, comes a still from the final scene in Return to Reason, showing Kiki’s headless torso, deeply shadowed. Uncredited and untitled, she is there to illustrate Breton’s tedious recounting of a dream, the unknowable female body as stand-in for the unshowable male mind.

__________________________________

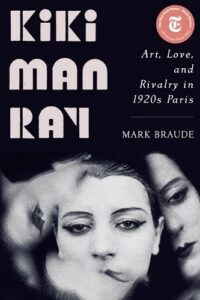

Excerpted from Kiki Man Ray: Art, Love, and Rivalry in 1920s Paris by Mark Braude. Copyright © 2023 by Mark Braude. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.