The little one stands at the edge of the wooden bridge in his wood and leather shoes. Three times he stomps his feet: klompf, klompf, klompf, left, right, left.

He waits.

*

Beside him, the larks have built their nests in the dry and chalky weeds and wild carrots that clutch around the earthfast timber posts.

Later, the birds will skim the air with the angled slice of a skipping stone.

*

The little one shuffles his feet, watching the leather laces of his shoes crust and clot with dust.

As the sun drops, he waits for a response from below the bridge, his body an insoluble black gesture against the tawny mustard sun.

It seems he’s a single letter—a shin or a nun—drawn there by some unseen hand, writ dense upon the fading sky.

*

The little one sips the air for a moment before he sings a school song thinly between his lips, a comfort, but not loud enough to drown out the awaited rompf rompf rompf answering from the creatures beneath the bridge.

*

Never is the little one to walk home alone and cross the bridge by himself. There are beasts there, says the old man, who are hungry for the taste of his grandchildren.

Instead, he is to trace the lacy pattern of the forest pathway and follow it until he comes to a red wooden bench the old man carved for him with a chisel and mallet. He is to sit there and wait until the old man meets him, and walks him safely across the bridge, and then home together, talking of the day.

The bench has the little one’s name written on it deep in the birch wood, and that of his sister.

But the little one won’t sit there, because that’s where the bridge beasts will come looking for him.

*

The little one waits at the edge of the wooden bridge, preparing for battle with its ogre below. Although the flies are silent still, the seedpods whirligig down upon the faraway and empty bench, siliculed as a wedding night.

The little one watches for movement of the dreaded ones in the pale spectacle of the viburnum. Beyond its white blossoms the bridge beasts guard a village alive with larvae, their business repulsive, exclusive, executive, not braced by bone or spine. Early summer as impossible as a pogrom.

Deeper in the forest the young men have felled branches and stacked them into vaulted cones, and crawl inside with their young women.

There are gray-headed ravens too, mated for life, and a thousand hoofed and padded feet traversing the forest floor, all pushing the seedpods deep down into the sorrel roots and loam.

Seed becomes tree, grave becomes cradle.

*

The little one is not to cross the bridge because the old man doesn’t want him seen lingering near a source of water. Half of Bremen dead. Half of Hamburg, and even more in Köln.

Plague sickness impervious to punishments or constraint: an ache that rises in the skull, a stomach set sail upon uneven seas, then high fevers and private swellings that fasten on to the afflicted, torment them, and move on.

Once-blond skin now showing the wild purple stains and sores of elderberries.

The little one is not to go near water, said the old man, because already there is suspicion around the wells, and accusations the circumcised ones have denied: the secretive mystery of kiddush cups filling the rivers with scourge.

But the knives and clubs and axes glisten with a proclivity for mobs.

*

The little one removes his new shoes before crossing into the dominion of the bridge beasts. Before crossing puddles such a purplish color of mud, an uncertain hue that’s half human, half soil.

Carry the leather shoes high so as not to muss them. Make no noise to awaken the beasts of this bridge to the village.

Nonetheless, the hum brum hum in the oxlip as enormous flies draw near, riding light as though along a foamy rim of beer.

*

At night, after the villagers, after the torches, after the torn hair and all the voices, the rats descend from the bridge to swim in the river.

After the villagers, exhausted, after the little one waited too long at the bridge, after the others playing at monsters along the riverbank.

High socks, low shoes, and ducklings float now beneath the bridge. Little elbows, damp and unhinged in water made not for limbs but fins.

Sinking, and then resting amidst pale leaves underneath, where the sun cannot reach but the bridge beast can. The water the color of children, unripe.

*

After the bodies are claimed. After there was too much blood. Amidst the echoes of such unsacred sounds, the cow again culls swaths of oxlip, yellow, from the riverside. Alongside it, the water buttercup rises above the wet, its stalks curving away from the broken necks below.

Clean cloths are found for the little girls. Clean cloths for the little boys.

The shrouds will soon get muddy within the common grave.

The only thing greater than the bodies of our children is the Shema, says the old man, and he rocks back and forth, the words of the prayer falling from his mouth like teeth.

*

Villagers say: The shouts of the children were indistinguishable from the cries of animals, or dogs surprised by pain. And, Everywhere the bluebottle fly. A plump fellow, fat and firm.

But our old men lament, Enough to make a minyan, that’s how much of us he has in him, this fly, come to visit from our generations. Fed from stacks left upon the offal heap.

With the bitter humor of the mourning. Who can say our children are dead when the fattened flies beneath the bridge yet live?

__________________________________

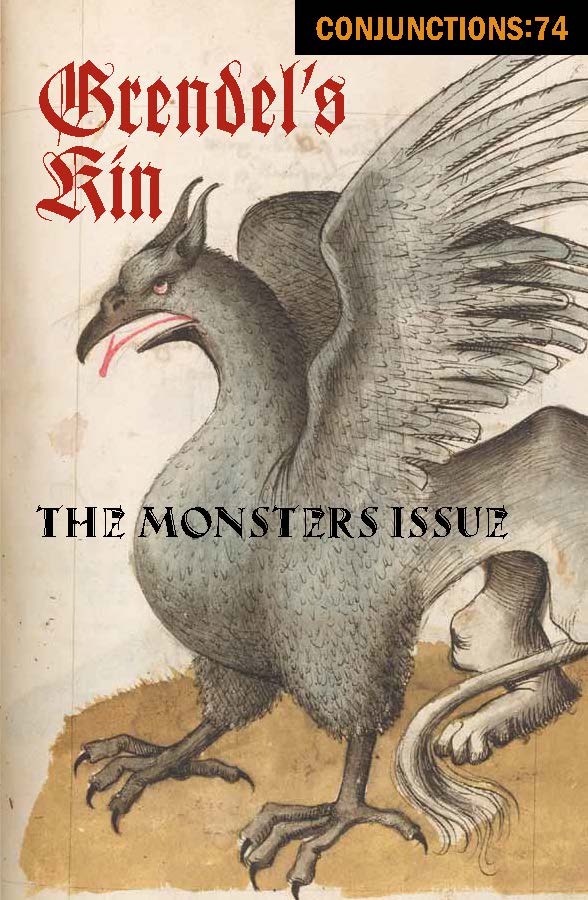

Excerpted from Conjunctions:74, Grendel’s Kin: The Monsters Issue. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.