LOST IN THE STRANGE, DIMLY LIT CAVE OF TIME

I live in Hamburg. I have a German passport. My place of birth lies past distant, unfamiliar mountains. Twice a week, I go running along the Elbe River I know so well, and an app counts the miles I’ve put behind me. I can barely imagine how someone could get lost here.

I am a fan of Hamburger SV. I own an expensive racing bike that I practically never ride because I’m afraid someone will steal it. I recently took a visit to the botanical garden, sur-rounded by stuff in bloom. I asked a guy wearing all green and a name tag if there was a sorb-apple tree in the garden. No, he said, but there are plenty of interesting cactuses.

People occasionally ask me if I feel at home in Germany. I alternate between saying yes and saying no. They rarely mean it to be exclusionary. They justify the question, saying: “Please don’t take it the wrong way, my cousin married a Czech.”

Dear Alien Registration Office, I was born in Yugoslavia on March 7, 1978, a rainy night. Since August 24, 1992, a rainy day, I have lived in Germany. I’m a polite person. I don’t want anyone to feel uncomfortable just because I’m not Czech. I say: “Isn’t Bratislava beautiful?” Then I say: “Hey, is that Axl Rose from Guns N’ Roses?” and when the person I’m talking to looks, I turn into a German butterfly and flutter away.

My three-year-old son is playing in a front yard near our apartment. The neighbors say that the owner doesn’t like seeing children in his yard. A cherry tree is growing there. The cherries are ripe. We pick them together. My son was born in Hamburg. He knows that a cherry has a pit, a Kirsche has a Kern, and that a Kern is also a košpica and a Kirsche is also a trešnja.

I was shown cherry trees in Oskoruša. One man showed me his bear fur, another his smokehouse. One woman talked on the phone to her grandson in Austria and then tried to sell me a cellphone. Gavrilo showed me his scar, which looked like giant teeth had made it. There were some things I wanted to see and hear, others not so much.

When I asked Gavrilo how he’d gotten his giant scar, he handed me a few blackberries and tried to give me a piglet as a present, and far up above, in the mountains, a story hissed and spit and it started like this:

Far up above, in the mountains…

The story begins with a farmer named Gavrilo, no, with a rainy night in Višegrad, no, with my grandmother who has dementia, no. The story begins with the world being set alight by the addition of stories.

Another one! Another one!

I’ll take more stabs at it and find a lot more endings. I know how I work. My stories just wouldn’t be mine without digressions. Digression is my mode of writing. My Own Adventure.

You find yourself in the strange, dimly lit cave of time. One passageway curves downward, the other leads up-ward. It occurs to you that the one leading down may go to the past and the one leading up may go to the future. Which one do you decide to take?

I have a hard time concentrating. I am reading about dementia and snakebite poisoning in the Eppendorf University Clinic library. A medical student is sitting across from me holding index cards with illustrations of organs. She spends a lot of time on the liver.

Gavrilo handed me another schnapps.

I offer the medical student a hazelnut wafer but she doesn’t want a hazelnut wafer. A tiny impulse, the idea of an idea, is enough to make me lose what is happening in the main event—now a memory, here a myth, there a single remembered word.

Poskok.

The non-main event gains weight and soon seems indispensable; the snake looks down at me from its tree and into me from my childhood; the remembered word, the semantic panic, I choose the passageway leading down and just like that I am thirty years younger, a boy in Višegrad. It’s summer, a summer in the restlessly dreaming eighties before the war, and Mother and Father are dancing.

A PARTY!

A party for Father and Mother in the garden under the cherry tree. Music is playing on the porch as Mother twirls under Father’s arm. The radio is playing for them. I’m there, but the party is not for me and means nothing to me. I hear the mu-sic and don’t understand what my parents understand. I sweep the porch. I sweep the porch with a child’s broom that doesn’t sweep very well. It’s missing the most important thing, it’s missing what makes a broom a broom: the plastic “bristles” are too far apart from one another. Anything smaller than a cherry slips through them. I scrape along the porch in time to music not meant for me.

The dog barks at my parents, jumping around their legs. It’s not our dog. Our only pets are birds prone to melancholy and hamsters quick to die. The dog was here yesterday too. My parents act like they don’t notice him, or at least don’t take him seriously. He gives up and turns his attention to something hopping along in the grass.

My parents are moving in a way that makes me not want to hang around them. I let the broom drop with a deliberate crash. They keep dancing.

I follow the wandering dog to the field where the Roma have set up their stands and bumper cars and merry-go-round. The dog sniffs at some bushes. It’s boring.

My parents showed affection to each other less often than they did toward me.

A few hours before my parents started dancing, Father had wanted to explain to me how canalization worked. He dropped a little red wooden ball into the drainage canal and we ran to the spot in the river where he thought the ball would have to come out again—an opening in the dike. We ran fast, Father and I. It was great, running somewhere together at top speed so that we wouldn’t miss what was going to happen.

Someone was fishing from the dike. Hook and bobber on his hat. Father slowed down, stopped, and, still out of breath, started chatting with the fisherman. I still remember thinking: No, it can’t be! He can’t just be abandoning what we came here for. If nothing else, his own heavy breathing must remind him!

I said something. I pointed to the world. I said: “Father . . . The ball!” Father raised his arm.

I squatted. The men got louder. The fisherman’s name was Kosta. Kosta and Father argued and laughed. Maybe that’s what Father wanted to teach me: that you can have friendly joking and bitter cursing on a Saturday by the river. But I knew that al-ready. It would have been something new if Father’s belligerence had grown to the point of pushing the other man into the river.

Push him, Father! I thought. I had half a mind to do it myself. The stupid little bell on the line tinkled, the man went to work and caught something.

We wouldn’t find the red ball. I wanted to throw another one in. Father stroked my hair.

Back home he did push-ups (thirty-three) in the yard, fell asleep, woke up, took off his shirt, mowed the lawn, sent me for the newspaper, read. Father read and sweated, his neck hairs sticking to his skin.

He called me over to read me something. He was already furious again. Maybe he wanted to share his anger, same as with the fisherman. Some people from some academy in Ser-bia had written something or other. I didn’t understand every-thing Father said. For example, I didn’t understand the word “memorandum.” I understood “serious crisis,” but not what the crisis was. I knew the word “genocide” from school, but here it wasn’t being applied to Jasenovac, it was about Kosovo. “Protest” and “demonstrations” I sort of understood, and I could also picture what “prohibition of assembly” meant. I just didn’t know why the demonstrating and assembling were prohibited, and whether Father thought that was good or bad. I understood “riots.”

I had questions. Father, a calm man, was crumpling the newspaper and screaming, “Unbelievable!” I didn’t ask any of my questions.

He clambered up the cherry tree and back down it. He dug a hole and shoveled the dirt back into it. He turned on the radio and found music. The screen door rattled and Mother slipped out of the house as if called into existence by the tune. My parents hugged each other. Mother fell into Father’s arms so naturally that it was like they’d agreed to it beforehand. They danced and Father wasn’t mad anymore—it didn’t go together, everything else goes with anger but not hugging and dancing.

At the fairground: I call the dog’s name. I pet the dog. I ask the dog: Whose dog are you? His quick tongue is orange. The dog finds a piece of fabric in the bushes, blue and white and

We wouldn’t find the red ball. I wanted to throw another one in. Father stroked my hair.

Back home he did push-ups (thirty-three) in the yard, fell asleep, woke up, took off his shirt, mowed the lawn, sent me for the newspaper, read. Father read and sweated, his neck hairs sticking to his skin.

He called me over to read me something. He was already furious again. Maybe he wanted to share his anger, same as with the fisherman. Some people from some academy in Serbia had written something or other. I didn’t understand every-thing Father said. For example, I didn’t understand the word “memorandum.” I understood “serious crisis,” but not what the crisis was. I knew the word “genocide” from school, but here it wasn’t being applied to Jasenovac, it was about Kosovo. “Pro-test” and “demonstrations” I sort of understood, and I could also picture what “prohibition of assembly” meant. I just didn’t know why the demonstrating and assembling were prohibited, and whether Father thought that was good or bad. I understood “riots.”

I had questions. Father, a calm man, was crumpling the newspaper and screaming, “Unbelievable!” I didn’t ask any of my questions.

He clambered up the cherry tree and back down it. He dug a hole and shoveled the dirt back into it. He turned on the radio and found music. The screen door rattled and Mother slipped out of the house as if called into existence by the tune. My parents hugged each other. Mother fell into Father’s arms so naturally that it was like they’d agreed to it beforehand. They danced and Father wasn’t mad anymore—it didn’t go together, everything else goes with anger but not hugging and dancing.

At the fairground: I call the dog’s name. I pet the dog. I ask the dog: Whose dog are you? His quick tongue is orange. The dog finds a piece of fabric in the bushes, blue and white and red, like the flag. Unbelievable, I whisper. The dog smells like freshly mown grass. I bore the dog.

A boy whistles through his teeth. The dog breaks free and runs to answer the summons. The boy is my age, and right away I know that he can do lots of things I can’t. He waves me over. He performs for me. He walks on his hands. I turn away, I’ve seen enough. Everything else he has to show me I can just as well imagine, I console myself in my cowardice.

I slink home. Father and Mother are not in the yard any-more. On the radio, two men are speaking seriously to each other, then they both laugh, like Father and the man by the river. It’s like everything can be everything at once, serious and funny, furious and dancing.

What are the chickens doing? The chickens are hanging around in the summer. I peek between the boards into the hen-house. Rays of sunlight slice through the air. I go in, thinking I’ll look for eggs. Sitting on the platform is the snake.

What do you say to a snake?

“Prohibition of assembly,” I whisper. The snake raises its head. It smells in the henhouse the way it always does. The radio is talking about the weather. High of ninety-five. The snake slithers down from the platform.

“Protest!” I shout. Or: “Poskok!”

Father yanks me out of the henhouse. I struggle, as if he were trying to hurt me. Father’s blue faded jeans. Mother puts her hands on my shoulders and turns me to face her, trying to make me look at her. So now she’s dancing with me. What I actually want to look at, though, is: Father versus the snake.

Don’t be scared, Mother says.

I’m not scared of any snake!

Father brings the rock from the garden. Father, on the threshold of the henhouse, raises the rock above his head. He walks in, trying to get closer to the snake, and the snake is trying to do something too, probably get out. It had it good before we showed up. It flows toward the door, toward Father, is it about to jump? Father takes a step back and the radio plays more dance music.

Father shows me the dead snake.

I ask if I can hold it.

I hold the snake, and think: This isn’t a snake anymore. Father is Father, covered with dust. It would have been so great to find the red wooden ball.

The snake is heavier and warmer than I’d imagined. Holding it like this is like not knowing what to say.

“Were you scared?” Father asks.

Why is everyone always talking about being scared?

“Were you?” I ask back.

“It wasn’t too bad,” Father says. He wipes his brow with the back of his hand and then wipes his mouth. Dust and sweat. I can’t help but think: Disgusting.

Father says, “Poskok. It jumps at your throat and sprays poi-son in your eyes.” He pinches my cheek, and then takes Mother’s hand.

That was my parents’ last dance before the war. Or the last I witnessed. I never saw them dance in Germany either.

Father washed himself off with the garden hose. I dug a grave for the snake. It’s still there: poskok. Unbelievable.

_____________________________________________________

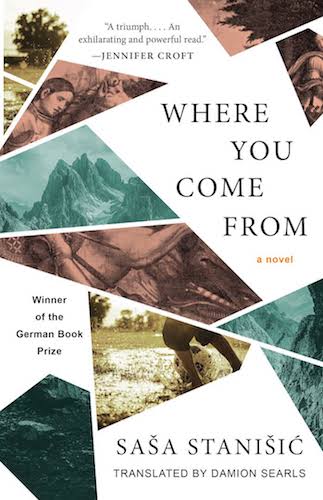

Excerpted from Where You Come From: A Novel by Saša Stanišić. Published by Tin House. Copyright © 2019 by Luchterhand Literaturverlag, a division of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH, München, Germany. English Translation Copyright © 2021 by Damion Searls.