When the World Matches the Apocalypse in Your Novel

Kimi Eisele on Finding Light in the Darkness of a Financial Dystopia

When the Lehman Brothers investment bank fell in September 2008, I heard the news over a pay phone at the edge of a flowering garden. A cat on a sun-drenched rock flicked its tail, while my friend on the other end of the line said, “It’s happening. Your book. It’s happening in real life.”

I was at a writer’s residency north of San Francisco, working on a novel set in the aftermath of a global economic collapse and energy crisis—aka, the apocalypse. In short, the novel imagines how two characters, separated when the grid goes down, begin to adapt to the changes while yearning to find each another.

The window of my writing cabin looked out over a valley where most mornings, to my dismay, bulldozers shoved around tawny dirt. A housing development? A new road? Where had all the dairy cows gone? Somewhere below the mounds was the San Andreas fault line, which, when it shifted dramatically in 1906, caused one of the most significant and deadly earthquakes in US history. A century later, I wondered whether the bulldozers might trigger another quake. Meanwhile, the housing market had just crashed, and then the banks fell, and, as the country headed into a presidential election, Sarah Palin vowed to “drill, baby drill” for domestic oil in some of the nation’s the most pristine ecosystems.

All of which is to say that the apocalypse is always imminent. But sometimes it feels more imminent than others.

Writing a novel has kept me acutely aware of the ways real life can mirror fiction. This, of course, is the beauty of the genre. Something imagined on the page later plays out in real life. Or in fictionalizing the real, you uncover the deepest truths. But when the story is post-apocalyptic, this mirror can be rather terrifying.

When I started the novel, the U.S. was at war with Iraq, and peak oil warnings were sounding loudly, at least in alternative news outlets. Against that reality I began to imagine what it would really be like to lose not just light, but mobility, long-distance communication, instant information, central governance, bananas, and the kind of entitlement that an economic system built on exploitation and convenience seemed to enable.

In my mid-20s, I lived in Ecuador where, because of a prolonged drought, the hydroelectric plant had to ration power. We took bucket baths and didn’t open the fridge and learned to let go of plans to, say, cash a check at the bank. Some years later, the Ecuadorian economy collapsed; to end the crisis, the president adopted the U.S. dollar as the national currency. Depending on where you stood, this was wise policy, a perverse act of the “invisible hand,” or a thinly disguised imperialist exploit.

What happened in Ecuador wasn’t as comprehensive a collapse as the one I was fictionalizing, but from it I knew that it was possible for people to maneuver through a certain kind of desperation and come out okay, maybe even stronger. My novel’s origins had something to do with wanting the world’s superpower—with its almighty dollar, its techno-gadgets, its jingoistic “We’re number one!” chants—to experience desperation, too. Perhaps this was a kind of literary revenge, but more honorably, I wanted think about how those of us in the industrialized north might get along with less power, especially if we were going to have to wean ourselves off cheap oil.

We know scarcity can lead to desperation and cruelty, but could it not also inspire kindness and care?But then the banks fell. I had just finished a third draft. I’ll miss the boat, I thought. The crash is now, and no one will have my book to read. But I kept writing, and then another boat came. Swine flu. And another. The BP oil spill. Then came the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, and Hurricane Sandy on the U.S. Atlantic coast. The Pinta tortoise went extinct, then the Bramble Cay melomys, then a Hawaiian songbird called the Po’ouli. Disaster, destruction, death.

In the world of my novel, everything goes dark. A cyberattack kills the internet. Flu comes, and terrorists. The government shuts down. Everyone loses something.

To survive, my characters learn to trade skills and goods—bike repair for jars of fruit and vegetables, tortillas for lard, chocolate for almost anything. They also find ways to reuse and recycle what can no longer be readily purchased. Sidewalk sales, flea markets, and old dumps become gold mines for the ingenious. For relief, some of the characters make lip balm and offer it to one of my protagonists, who dubs it “Apocalyp-stick.”

These adaptations were also reflections of real life. In my own neighborhoods and artist communities, friends have long traded architectural advice for home-cooked meals, paintings for medical treatment; I’ve traded writing, editing, and artwork for massage and physical therapy. For a time, I dated a serial “dumpster diver,” and I’ve known several people who make their living from reselling garage- and estate-sale scores.

I learned from my characters, too. When my publisher invited me to promote the book at a gathering of independent booksellers in Albuquerque this winter, I teamed up with KuumbaMade, an all-natural body care business run by a friend, to make a small batch of lip balm as promotional swag. As it happened, I flew to the event—150 Apocalypsticks in hand——on day 33 of the government shutdown earlier this year.

My main job was to sit in a ballroom along with 100 or more authors, each of us at a table with advance review copies to give to owners and employees of the nation’s independent bookstores. Because our fascination with the end times never ends, mine wasn’t the only post-apocalyptic book in the room. But while such tales often linger in darkness and disaster, my novel takes a different tack.

We know scarcity can lead to desperation and cruelty, but could it not also inspire kindness and care? After 9/11, New Yorkers talked about how nice everyone was to each other, at least for a spell. Where I live in the US-Mexico borderlands, I’ve seen how adversity can breed generosity. I’ve been served generous meals in homes made of shipping pallets and without electricity or running water. I’ve seen it in the way cacti store water, make slivers of shade with the thinnest of spines, and even give fruit in the hottest months to countless animals and people, too. I’ve seen it in the way compassionate humanitarians tend to migrants crossing the desert into this country or offer legal aid to those already here.

I wanted to write an unimaginable darkness and then imagine how people might come together to find new sources of light. Who would help whom and how? Where would people find faith and what stories would lead them there? I wanted a tale of adaptation, resilience, and love. That’s what I wrote.

Then came the 2016 election, which didn’t go the way I’d hoped. The aftermath has brought so much loss and a seemingly continuous unraveling.

But it was in this bleakness that I sold the novel. Every day is also an invitation to look for the opposite of misery.

So when I found myself in the conference ballroom and saw the independent booksellers streaming in, hungry for books and to meet the authors who wrote them, I thought: This, too, is what resilience looks like.

Not so long ago, it looked like the end of the world for independent book stores, given the swift rise of online retailers and their ever-expanding power. But while many stores went under, the industry didn’t die. In fact, between 2009 and 2015, the number of indie booksellers grew by 35 percent, according to a report by the American Booksellers Association (ABA).

This survival, says Ryan Raffaelli, a Harvard Business School professor who studies how industries adapt to technological change, can be attributed to three things: community, curation, and convening. Indie booksellers support the local economy, connect to community values, foster personal relationships with customers, and convene public events where people can come together to share time, space, and ideas. ABA itself also had a hand in the resurgence, offering an umbrella organization under which indie sellers could swap strategies, create partnerships, and collectively strengthen their purpose. In other words, helping them to weather the storm.

I wanted to write an unimaginable darkness and then imagine how people might come together to find new sources of light. Who would help whom and how? Where would people find faith and what stories would lead them there?Booksellers from all over the country looked me in the eye, shook my hand, asked me questions, and said they were excited to read my book. They delighted in the Apocalypstick, too.

All of this seemed to exemplify—in the midst of that government shutdown—the flip side of despair. Hope and healing sometimes happen in the midst of situations that seem utterly dire.

It turns out those bulldozers in front of my writing cabin weren’t making space for a new housing development, but for a restored version of the historic tidal marsh that existed before dozens of dairy farms came in. Since my time there a decade ago, it’s now a thriving wetlands, where shorebirds and waterfowl reside or refuel during long migrations. Unexpected beauty sometimes arises after everything gets torn to bits.

The apocalypse is coming, as it has before and will again. But if we look for resilience, we will find it, too. It will be a balm.

______________________________________________

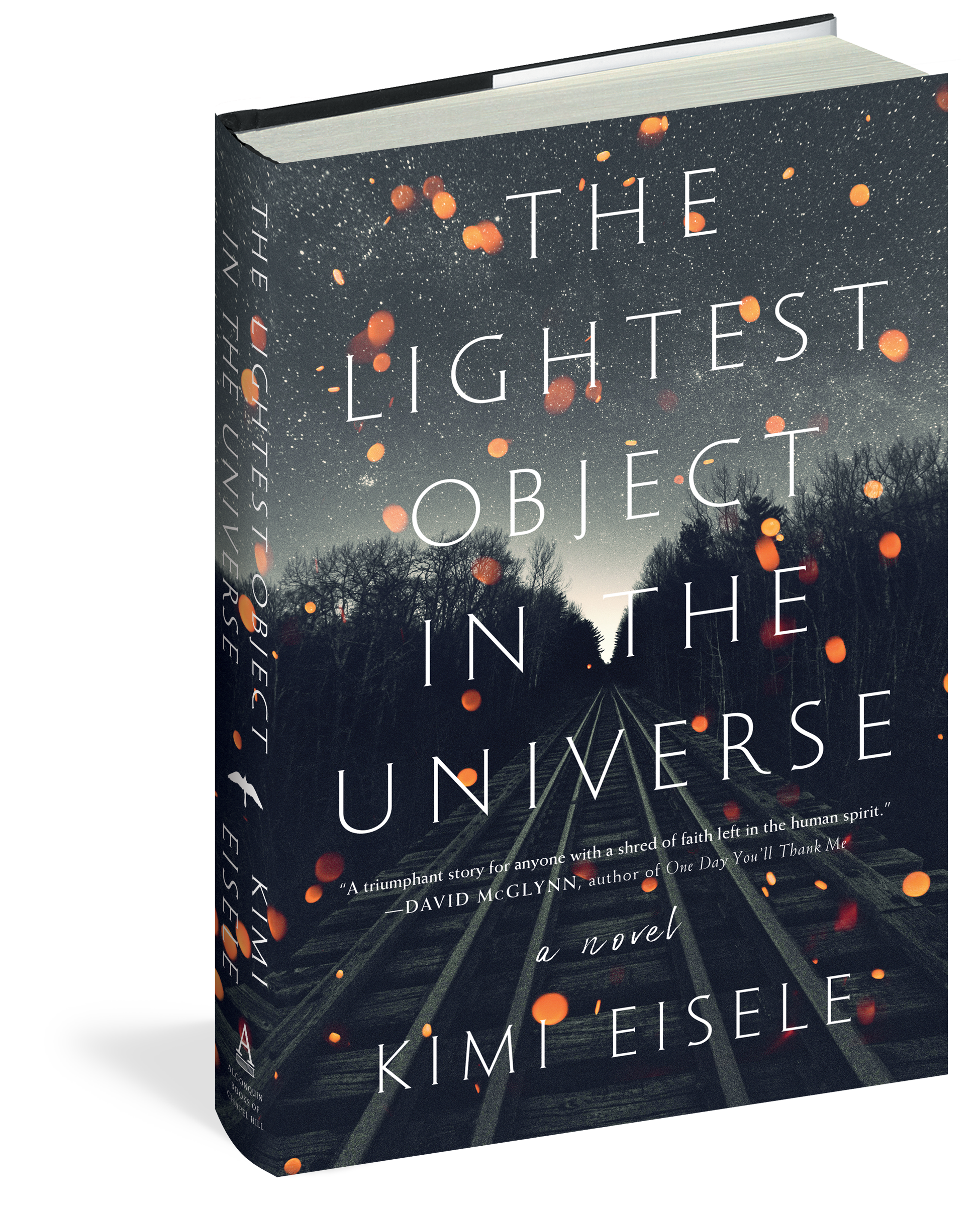

Kimi Eisele’s The Lightest Object in the Universe is out now from Algonquin.