When the Dismissive Editor in Your Head Is Your Father

Jonathan Wells on Finding a Way Back to Writing on His Own Terms

Having washed out of the Air Force during the early years of World War II for flying out of formation, my father talked himself into the job of entertainment director at a GI training camp in Greensboro, North Carolina. There, he watched as young men, mostly from the inner cities, were whipped into shape in six weeks before being shipped overseas. This experience was the foundation of his ideas of fatherhood: discipline, order and obedience.

When I came under his command less than 20 years later, I was 11 years old, shy and bookish, as well as small and underweight. To address the obvious physical inadequacies and in spite of the fact that both he and my mother were small-boned and five foot seven and five foot two respectively, he implemented a regimen of exercises and practices that he had observed in Greensboro: jumping jacks, pull-ups and push-ups. To help me gain weight, he insisted on chocolate milkshakes and finishing what was on my plate. His guiding principle was, “With eating comes the appetite.” This felt like an order which I had no choice but to obey.

At the same time that he worked on my physique, he became interested in my intellectual development. His first concern was about my reading style. He argued that I was spending too long on each page, committing the sin of reading each word. This interfered with getting to the heart of the information, he claimed. “The helper words, articles, supportive verbs aren’t important. You must learn to read vertically. If you read every word, it will take forever and you’ll miss the gist. Only academics read horizontally. You don’t want to be a horizontalist, do you?” In case I was unsure what he meant, for him, an entrepreneur with a growing business, becoming “academic” or an academic would represent failure; a life of stasis and inaction.

Once he had addressed my reading problems, he moved on to my social interactions. I mumbled. I didn’t look at people when I spoke to them or they spoke to me. I didn’t shake hands. “Look them in the eye,” he insisted. These instructions were also features of his salesmanship, of reassuring the customer that he was decent and honest, that he could deliver the goods and services that he had promised. I followed his directions as superficially and subversively as I could without an overt refusal.

To show my progress to the world, he fixated on my winning the speech contest at the pre-prep boys only school where I had been sent in sixth grade. Each year the winning speaker won a silver cup and a gift from the headmaster. He sold this to me as a project that we could work on equally and together. “You pick the subject, Jon. I don’t care what it is,” he offered grandly.

Having just spent Spring Break on a houseboat in Lake Okeechobee, Florida, with my grandparents, I chose the plight of Everglades National Park; how the encroachment of civilization had damaged the ecosystem and, unless drastic measures were taken, the animal inhabitants as well as the natural order itself would be at risk. To start, my father asked me to write a 500-word essay on the topic. I spent a few weeks of research in the school library, writing and rewriting before I showed it to him. I stood next to him as he read it with great deliberation. In his right hand he held his favorite red felt-tip pen and began slashing immediately. I could hardly bear to watch as he read through it marking it up as if he were a line editor, not a businessman. By the time he was finished, the page was blood red. “Not bad,” he said. “Try again.” He handed it back to me before picking up the telephone to call one of his salesmen in the Midwest as he did almost every night after dinner.

After endless drafts, each almost as red as the preceding one, I arrived at one that met his approval. However, I realized that with each edit my voice had been diminished. By the time he had accepted it, I had become a ghost in the process, present but ethereal. My original interest in the subject was reduced to nothing. I didn’t care what the judges would think of it or how it would be received by the audience.

As a man of the world—successful, brash, handsome, a ladies’ man—my father was almost impossible to resist, except through reticence and refusal. I ate as little as I could and for 24 years I didn’t write a word.The delivery of the speech was as important as the content, he believed. We practiced it hundreds of times until I learned exactly when to pause, where to build suspense, when to look up and gaze into the audience without losing my place. “You are not delivering a speech, Jon. You are selling a point of view. It’s one you care about, you told me, so let’s not put people to sleep.” By the time it was my turn to make the speech publicly I knew it by heart, recited it in my dreams, and didn’t care whether I won or not. When I did win, I let the cup tarnish on my bookshelf. There was nothing in it that was mine.

In spite of my father’s meddling, and as if it by itself it represented my freedom, I nurtured the idea that one day I would be a writer. There was nowhere I felt more comfortable than in a bookstore or reading in my bunk bed under the night light. I tried my hand at poems first and then at fiction. But no matter how hard I worked on the admittedly thin material, I felt that there was an editor in my head who dismissed every word I chose and reversed the order of every sentence I wrote. After numerous attempts in different genres, I gave up and said to myself that one day that editor would move out and I would be able to hear my own thoughts again.

The Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg wrote in an essay on parenting, “It is our job to be in the next room but not the same room.” With my father’s occupation of my body as well as my mind, his residence in those years was unbroken. As a man of the world—successful, brash, handsome, a ladies’ man—my father was almost impossible to resist, except through reticence and refusal. I ate as little as I could and for 24 years I didn’t write a word.

In the intervening time I read and waited, taking occasional notes about the world and myself and storing them until I could find a way to use them and trust them. It was not until I reached my forties that I felt sure enough and had enough distance from him to attempt writing again. By then, my father was in his seventies and had lost interest in being my editor long ago. My ambitions were modest. I hoped that one day someone somewhere would want to publish something I wrote. That was my only goal. When my first poem was taken by a literary journal, I was incredulous. When my first book of poems was accepted, I hid the contract behind my bookshelf in case someone would find it and take it away from me.

It was after I had written my first few poems that my mother was diagnosed with late-stage ovarian cancer. By that time my parents had divorced but were on friendly terms. One day my father, with whom I had become close, asked me out of the blue whether I had ever thought of writing again. With apparent disinterest, I showed him the few poems I had written including one about my mother’s illness. He read them quickly, looked up and said, “These are terrific, Jon. I didn’t know you could write. But if I were you I wouldn’t show them to your mother.”

__________________________________________________________

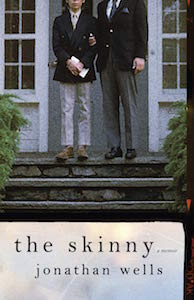

Jonathan Wells’ memoir The Skinny is available now via Ze Books.