When Predator Becomes Prey: Why Sharks Need Protection From Humans

Greg Skomal and Ret Talbot on America's Cultural Obsession With the Great White Shark

The summer of 1983 was hot. By Labor Day, the northern plains were begging for federal aid during the worst drought since Dust Bowl days. “We’re asking Uncle Sam to help where Mother Nature has cruelly neglected her responsibilities,” pleaded Missouri’s governor. Record-breaking heat also scorched the Northeast. July was the hottest month ever recorded in Boston, where the temperature exceeded ninety-five degrees seven times. The Baltimore Orioles were having a great season, and the Police and Michael Jackson topped the pop charts. A gallon of gas cost $0.96. The first American woman and the first black astronaut went into space aboard the space shuttle, and Motorola released the first mobile phone. The third installment in the Jaws franchise, Jaws 3-D, turned out to be a disappointment—Return of the Jedi was the film to beat.

Despite the performance of Jaws 3-D—the best the New York Times could muster is to say it’s “probably no worse than Jaws II”—the summer of 1983 was a great one for me. I liked the movie in the way anyone passionate about a thing has a vested interest in seeing a movie about it, but there was no denying that, when it came to sharks, fact was better than fiction. As my father was fond of saying, I was “living in the key of G”—marching to the beat of my own drum—as I worked daily at the Narragansett Lab alongside scientists on the cutting edge of shark research in the northwest Atlantic.

In addition to tournaments, like the Bay Shore tournament I worked in July, the lab also got access to shark specimens by way of commercial fishermen or recreational anglers who knew to call Jack if they landed a “rare-event species.” It’s what I loved most about my job—the fact that although there was the monotony of data entry and other jobs around the lab, each day also held the promise of something completely unexpected. I was continuing to hold out hope that one of those rare-event species calls would be about the shark that inspired it all for me: the white shark.

Few people were asking the question of whether sharks might need protection.

I knew white sharks were present in New England waters, but the data confirmed the anecdote that they were not common. The reasons they were rare are unclear, as little was known about the western Atlantic population. Since the beginning of the Cooperative Shark Tagging Program in the early 1960s, just twelve white sharks had been tagged—one in 1968, one in 1969, one in 1973, one in 1977, two in 1979, one in 1980, three in 1981, and two in 1982. Compared with sharks like the blue shark—with more than one thousand blue sharks tagged some years—the white shark remained elusive.

In other parts of the world where white sharks were more common, some scientists were starting to express concern. In 1982, a commercial fisherman landed four white sharks near California’s Farallon Islands, an established white shark hotspot. Scientists closely studying that population observed a marked decrease in predation events in the weeks that followed. This surprised them because seal and sea lion populations were skyrocketing following the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, which made it illegal to kill, harm, or harass the white shark’s favorite prey item. There should be more sharks. Instead the number of observed predation events was cut almost in half, and it took several years to return to the levels previously observed. Could the removal of just four individuals have so significantly affected an otherwise healthy population with a plentiful food source?

In other places where recreational fishing for white sharks was popular, researchers reported similar trends. One of the most dramatic examples was a location in Australia known as Dangerous Reef. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, it was a reliable place to find white sharks. Scenes from both Jaws and Blue Water, White Death, my favorite film about white sharks, were filmed there, and it’s where Zane Grey traveled in 1939 to fish for white sharks. By the 1980s, scientists reported that increased fishing pressure was coinciding with very few white sharks observed. Leading shark advocates and researchers like Valerie Taylor and Jacques Cousteau expressed concern about the species and its ability to withstand fishing pressure.

It wasn’t just white sharks about which there was concern. The more scientists learned about the biology and life history of sharks, the more they realized how different sharks are from other fishes. Sharks grow slowly, mature later in life, produce low numbers of well-developed young, and live a long time. In many ways, they are more like mammals, and one need only look at whales to understand the vulnerability of this evolutionary strategy in the face of a predator as effective as humans. Despite these concerning signs, by 1983 there was still no widespread effort to protect sharks, and in the western North Atlantic, sharks remained entirely unmanaged.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Photo courtesy of the author.

The focus for so long had been “to rid the seas of sharks” and “end the shark menace” that few people were asking the question of whether sharks might need protection. Jack, who was part of the federal government’s effort to promote shark fishing in the 1960s, was one of those people asking a new question. In 1976, sportswriter and shark fisherman Nelson Bryant wrote in the New York Times that Jack Casey was pondering the question of whether sharks needed protection:

The motion picture Jaws and the book that spawned it accelerated the interest in sharks and shark fishing and may also, says shark specialist John Casey at the Narragansett Marine Laboratory, have contributed to increasing concern for the well being of the species. Not very much is known about the various sharks but it is clear that they are vulnerable to overfishing….

To be clear, Jack was not against shark fishing. He continued to actively collaborate with shark anglers and shark tournaments because he believed they remained the best way to access specimens for study. Expressing concern about overfishing and maintaining strong relationships with shark tournament organizers were not mutually exclusive in Jack’s eyes, and he was not alone in that position.

Just a year after Jaws was released, an article in the Naples Daily News about the ninth annual Florida Lake Worth US Open Shark Tournament posited that shark tournaments might soon be a thing of the past. It’s “a contest whose days may be numbered,” wrote the reporter. Tournament organizer Gerald Mickley was quoted saying that initially the purpose of the tournament was indeed to reduce shark populations, but that may be changing. While some types of sharks are “absolutely dangerous,” he said, he believed others “may be becoming endangered.” The tournament’s scientist, Regina Skocik, a shark researcher affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution and the author of The Sharks Around Us, was more direct, arguing that there are reasons for not killing sharks. “Sharks are not all wild meat-eaters. Some have specialized dietary habits. By destroying them, we’re destroying the ecosystem of the ocean.”

Like Jack, Skocik believed there was also scientific value in shark tournaments even as she encouraged caution. “The only reason we know as much as we do about these species is the fishing public,” she said, “and it’s the people who are fishing for sharks and who are willing to fill out questionnaires who are helping the most.” She was not opposed to shark fishing tournaments, she said. “We do need the vital data.”

By 1983, I hadn’t given too much thought to shark conservation. Working for Jack, I’d seen the fishing public’s value to shark science, and I found the work fascinating. There was no coherent opposition to shark tournaments in the early 1980s (that would come later) and shark tournaments were growing in popularity. From my perspective, there were going to be dead sharks on the docks, and not utilizing them for science was a waste. In addition to the data gleaned from shark dissections, I also felt a more visceral connection to opening up a shark on the dock. There was a powerful narrative that aligned this messy, bloody work with the archetype who inspired my own quest to become a marine scientist: Matt Hooper. During the summer of 1983, I thought a lot about the scene in the original Jaws movie, where Police Chief Brody (Roy Scheider), absentmindedly fidgeting with the foil on the neck of a bottle of Beaujolais, says to Hooper, “Why don’t we have one more drink and then go down and cut that shark open?”

In the movie, Brody and Hooper had watched a posse of local fishermen triumphantly land a large shark at the town dock earlier in the day. The fishermen are intent on slaying the man-eater that killed a young boy. The mayor, resolute in his decree to keep the beaches open and the tourist dollars flowing through the summer holiday, proclaims as fact the story sweeping the dock. This is the shark that killed the boy! It’s safe to go back in the water! A reporter and photographer are in the process of consecrating the narrative in what they hope will be a nationwide media blitz, because the shark attacks on Amity, like most shark attacks, will be national news. But Hooper remains rationally unconvinced. While other characters are motivated by political pressure, ego, and fear, Hooper, the scientist, focuses on objective truths—what he can observe, measure, and, ultimately, dissect.

The scene in the movie is rowdy. The crowd alternates between jeers and cheers—celebratory bedlam as the animal is hoisted aloft. It’s a mob wielding fishing rods and harpoons instead of pitchforks. One man has a rifle. Salty fishermen speculate on what species the shark is, as they peer into the blood-slathered, toothy mouth of a monster. Two arrows dangle from its flank. A large hook pierces its snout, causing the mouth to gape. It’s a lynching—a hasty conviction at the gallows without due process. A witch at the pillory. No evidence. No data. Yet at this point in the movie, most every person in the theater is rooting with the crowd on the dock. They are hoping this is the man-eater (even though they know their optimism will be short-lived—such is Spielberg’s magic). The audience is caught up in the frenzy of the hunt. The revenge kill. The vindication. Man triumphing over the monster and making the wilderness safe again.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Photo courtesy of the author.

It’s primal.

But that’s not the way I saw it sitting in the movie theater in Fairfield, Connecticut. I saw something entirely different—something that would ultimately change my life and lead to me dissecting sharks alongside Jack and Wes up and down the New England coast in the summer of 1983. I saw Matt Hooper approach the shark steadfast and determined. He’s unemotional against a backdrop of hysteria. He observes the animal as a scientist. He’s rational. Thoughtful. Deliberate. Objective. Blocking out the noise, he acts methodically. He measures the shark’s mouth. He calmly identifies it and uses terms like bite radius as he makes mental notes of the animal’s measurements. He does not think this is the shark that killed the boy, but nobody wants to hear his opinion, however well informed it may be. The desire to slay the beast is so strong that even Brody buys into it…until the awkward scene with the Beaujolais and the ensuing dockside dissection by flashlight, which proves this is not the man-eater.

There is something elemental about sharks—something hardwired into the human brain that makes hunting them different.

Brody holds the flashlight. Hooper wields the knife. I was on the edge of my seat. It was so cool.

*

As the summer of 1983 progressed, I saw similarities between the scene on the Amity dock and the shark tournaments. There is something elemental about sharks—something hardwired into the human brain that makes hunting them different than hunting striped bass or tuna or marlin. The scene repeated itself from New York to Maine. Sharks hoisted from boats and hauled up onto the scale for weigh-in. The crowd cheered, as the announcer emceed the event over a loudspeaker with all the emotions of a sports commentator giving a play-by-play, complete with color commentary. The best announcers built suspense and manipulated the audience’s expectation to ensure an electrifying spectacle: “Behold this behemoth from the depths!” While all this was going on, the scientists, usually just a few meters away from the scale, measured and cut and recorded. They were seemingly immune to the raucous backdrop. They were eager to answer questions from the children fascinated by seeing the sharks’ insides—the size of the liver, the color of the muscle. The jaws. Everyone wanted to see the jaws.

It was like a three-ring circus, with the ringmaster controlling the audience’s response to these truly magnificent animals that, removed from their natural environment, became a prop used to fit a cultural narrative. Even a tournament favorite like the shortfin mako was turned into a man-eater when the snout was lifted to expose the jaws to the bystanders, who instinctually took a step back from the dead animal. “How would you like to see that coming at you in the ocean?” the announcer asked a woman in a bikini. It was no matter that the shortfin mako was implicated in fewer than ten unprovoked attacks on humans since 1850. This was theater at best, propaganda at worst.

By 1983, sportfishing tournaments in general had changed. They were no longer dominated by the exclusive, staid affairs put on by elite fishing clubs and populated by well-healed marlin and tuna anglers—anglers of means. Shark tournaments tended to go a step further, however. It was a morass of swagger, bravado, cheap beer, and diesel fumes—a little ragged around the edges, but immensely popular. Shark fishing, thanks in large part to pop culture, was the type of fishing where the angler could frame him- or herself as doing battle with a true monster at great personal risk. The annals of “provoked shark attacks” were full of minor injuries to anglers, but the risk of serious bodily injury—the loss of life or limb—was not borne out in the data.

Beyond Jaws, another reason shark tournaments were so popular is that shark fishing remains one of the most accessible forms of sportfishing for big-game fish in the Northeast. Whether you had a twenty-five-foot Boston Whaler or a forty-foot Hatteras, you could go catch a shark or take part in a shark tournament. By the early 1980s, billfishes and tunas were becoming harder to catch. Once plentiful in nearshore waters, these trophy gamefishes were now harder for anglers to find, forcing them to go farther offshore in bigger boats, with more fuel and plenty of time.

Sharks, on the other hand, appeared plentiful. Anglers and outdoor writers were no longer talking so much about “the shark problem” or “the shark menace.” They were instead extolling the virtues of shark fishing, and shark meat had entered the culinary lexicon as a substitute for more expensive swordfish and tuna steaks. Shark was even being marketed aggressively to the stay-at-home mom preparing dinner for a family of four. During the summer of 1983, the grocery chain ShopRite tempted its shoppers with “uniquely delectable, broiled mako shark steak” at just $4.39 per pound. “Get even,” the advertisement read. “Bite a shark!”

There is no question that, by 1983, sharks had gone mainstream, and I was in the thick of it.

__________________________________

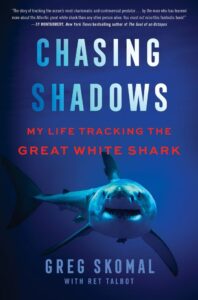

Excerpted from Chasing Shadows: My Life Tracking the Great White Shark by Greg Skomal with Ret Talbot, published by William Morrow. Copyright © 2023 by Gregory Skomal. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

Greg Skomal and Ret Talbot

Dr. Greg Skomal—in addition to being an accomplished marine biologist, underwater explorer, photographer, and author—is a leading white shark expert in the Atlantic. He is a senior fisheries biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and currently directs the Massachusetts Shark Research Program. He is an adjunct professor at the University of Massachusetts Intercampus Marine Science graduate program; an adjunct scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Massachusetts; and a member of the Explorers Club and the Boston Sea Rovers. Greg has authored dozens of scientific research papers and has appeared in several film and television documentaries, including programs for National Geographic, Discovery Channel, PBS, and numerous television networks. He is a regular on Shark Week and Shark Fest and is the author of The Shark Handbook. He holds a master’s degree from the University of Rhode Island and a PhD from Boston University. He lives with his family in Marion, Massachusetts.

Ret Talbot is an award-winning freelance journalist who covers ocean issues at the intersection of science and sustainability. His work can be found in publications such as National Geographic, Discover, Mongabay, Yale Environment 360, and other venues. As a science writer, he has embedded with marine scientists around the world, including places like Papua New Guinea, Sulawesi, and Belize, and he frequently works closely with scientists like Greg to bring compelling stories about science to a genera audience. He lives on the coast of Maine with his wife, Karen Talbot, who provided the illustrations for this book.