When Pakistan Feels Like an L.A. Noir

Motels, Broken Dreams, and Mysterious Men Asking Questions

The inn could have been the set of an L.A. noir film which dealt in broken dreams, and violence. A two-storied quadrangular building of red brick with regularly spaced off-white balconies and off-white air conditioners looked onto a generously sized garden. In the center of the garden, a large empty swimming pool with an interior of fading blue paint and cracked cement. Rusted stepladders at either end extended halfway down into the pool. A magnificent peacock roamed the gardens, like a movie star who finds herself dropped into obscurity but is determined to maintain standards. A peahen, guinea fowls, and a black and white cat made up its entourage.

Eleven of us had stopped for the night at the inn in Larkana, a band of travelers from Karachi who had come to visit the nearby ancient site of Mohenjodaro. At sunset, the inn manager laid out a long table in the garden, so we could eat beside the swimming pool and listen to each other’s ghost stories. Eventually, in varying states of terror from the stories, nine of our party wandered back to their rooms until it was just my old friend Zain and me in a darkness broken only by the low-wattage bulbs of the inn. That’s when something more unwanted than ghosts appeared: two men whose questions about the foreigners traveling with us identified them as being from Military Intelligence (the other mark of who they were was their lack of need to explain who they were before they launched into questions).

By now the second adult male in our group—Bilal—had walked out into the garden as well, and stood nearby listening as one of the men, with a neat mustache and a red polo shirt, pulled out a pad of legal paper and started to question me (he had started with Zain, because of the gender pecking order, but Zain had only just met the foreigners for the first time that morning and couldn’t be of much help). The British citizen with Pakistani antecedents didn’t interest the man from MI particularly. But then he turned his attention to The Blonde (every L.A. noir movie needs one).

What is her husband’s name? he said. She has no husband, I answered. And her source of income? She’s a writer. So her father supports her, he asserted. Is he a businessman? No, I said, she supports herself. The man looked pained by my evasions. No one earns a living from being a writer, he said. What is her real source of income?

Somehow we got through the income question, but landed straight into the peculiarity of a single woman who doesn’t live with her parents. How is this possible? said the man from MI, at which point Zain launched into a long speech about the lack of family values in the West. This was, as he intended, convincing enough to move the conversation along. To which countries had my friend traveled? Did she have siblings and what did they do for a living? Had she been to Pakistan before, and why? Had she been to India? What were her books about? On our way to Larkana our van had stopped at the mausoleum of the Bhutto family—what had she said about it? She said it made her feel sad, I replied, though in fact we hadn’t talked about it at all. This could be interpreted in many ways, said the man. What kind of sad? I decide to look appalled. There were many bodies buried there, I said. The second man, who had been silent until now, turned to his partner. It’s a graveyard! he said. Exactly, I said. A graveyard! Where is the individual of any humanity who wouldn’t feel sad in a graveyard? (Urdu allows for an extravagance of expression that came in handy at this point.)

What does she think about the Bhutto family? the man persisted. On some instinct I said, Why don’t I call her out so you can ask her yourself? For the first time, the balance of power between us shifted. No, no, he said. She’s a guest here; I can’t disturb her.

I pressed home my advantage. I have answered your questions with an open heart, I said, and now it’s getting late and I have an early flight. How long do you intend to keep me here? The man looked distressed. I have also spoken to you with an open heart, he said. At this point the inn manager, who had been smoking a few feet away, tapped the man on the shoulder and said, Let her go now. Very soon after, he did.

They kept Zain a few minutes longer, but he too took the route of outrage rather than compliance and the interrogation concluded. Once we were all back indoors Bilal, who had been listening to the whole exchange, said, What they wanted from you was money.

Zain and I replayed every detail of the encounter to each other. The truth of what Bilal said became evident. The inn manager and these two men—who were not from Military Intelligence at all—were in on the scam together.

Just wait, Bilal said. Tomorrow morning the inn manager will give us an inflated bill that will include the sum of money he’d hoped to extract from us. And so it proved. Zain demanded a breakdown of costs, and the bill reduced by half. By the time we were on the flight to Karachi I had tamed the encounter into a story of much hilarity. (The Blonde—a biographer of Eleanor Marx who cut her teeth on antiapartheid activism—particularly enjoyed my description of her as someone who studied literature, goes to see ancient ruins, and writes biographies of people who died more than a hundred years ago, and therefore can’t possibly be expected to have any political opinions about the present.)

But beneath all the hilarity, there existed this truth: The inn manager and his accomplices could run such a scam because in all of us who have grown up in Pakistan there exists a terror of the men who proffer no ID, never explicitly state whom they work for, but maintain the right to ask any questions and carry out any actions in the name of security.

The plane dipped its wings; I looked down on Larkana, home of the Bhutto family, who dominate the imagination of Pakistan as no other family does. It wasn’t just the inn, but the city—no, the nation itself—which was the set of broken dreams and violence.

__________________________________

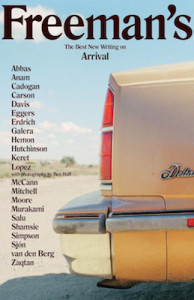

This essay original appears in Freeman’s: Arrival.

Kamila Shamsie

Kamila Shamsie was born and grew up in Karachi, Pakistan. She is the author of eight previous novels including Burnt Shadows, shortlisted for the Orange Prize, A God in Every Stone, shortlisted for the Women’s Bailey’s Prize and the Walter Scott Prize, and Best of Friends, shortlisted for the Indie Book Awards. Her novel Home Fire won the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2018. It was also longlisted for the Man Booker Prize 2017, shortlisted for the Costa Best Novel Award, and won the London Hellenic Prize. In 2023, her story Churail was shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award. Her work has been translated into over thirty languages. She is a Vice President of the Royal Society of Literature and was named a Granta Best of Young British Novelist in 2013. She lives in London and in Doha where she is Writer in Residence at Georgetown University in Qatar.