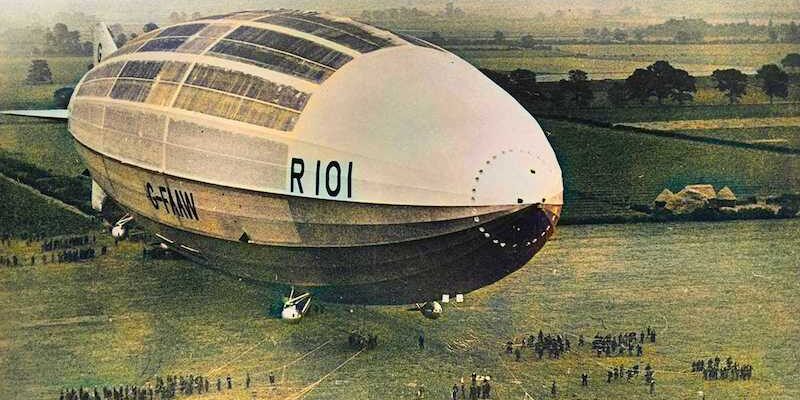

When One of the World’s Largest Flying Machines Crashed in a French Field

S.C. Gwynne Remembers the Tragic History of the British Airship R101

At just after 2:00 a.m. on October 5, 1930, engine mechanic John Henry “Joe” Binks is awakened in his berth by George Short, the engineer of the watch. Short has just left the nacelle where Binks works and knows that Binks is late. Binks jumps from his bunk. Short hands him a cup of hot cocoa and tells him that R101’s five engines, including the one Binks is responsible for, are in good working order. Binks’s graveyard shift is about to begin.

Binks, a cheerful, square-jawed Yorkshireman who was a member of the heroic crew of R33 on its wild North Sea ride, gulps down the cocoa, then heads aft, traveling about 150 feet along the narrow walkway that runs nearly the length of the ship. He heads for his engine car, where he climbs ten feet down a rope ladder to where his thrumming nine-foot-long, two-and-a-half-ton, 650-horsepower diesel engine with its enormous propeller awaits him. On his way to the ladder, he passes Michael Rope going the other way.

He sees Rope hoist himself up into the tangle of girders, wires, gigantic harnesses, and dark, surging gasbags.

What is Rope doing at this late hour? That is a good question. He is the man most responsible for the physical form of R101. But he is not part of the crew for the Egypt-India voyage and has no role in flying the ship. He is a passenger with no official duties. Yet there he is at two in the morning, ascending into the dim, cavernous spaces inside R101’s 777-foot-by-130-foot interior.

Rope, the strict Catholic who moved his family away from Cardington to avoid the alcohol-fueled culture there, has almost certainly not been drinking and socializing with the others. Most likely, he is up in the rigging at that hour because he is worried. Rope wrote the letter four months before raising an alarm about the outer cover, making the heretical suggestion that R101’s flight be delayed.

In the fall of 1929 he protested the letting out of his ingenious wire harnesses. He was ignored then, too. Rope knows that a failed cover means soaked gasbags, and waterlogged goldbeater’s skins tend to split along their seams. He is perhaps just acting rationally, checking on the cover and bags after seven and a half hours of rain and high winds.

The image is arresting. A man alone in a small white room, engines droning and clacking somewhere beneath him, above him so many sleepers, in berths he cannot see.

At the same moment, engineer foreman Harry Leech is in the smoking lounge, which is located on the center line of the airship, aft of the chart room and wireless room, and below the deck where passengers and off-duty crew sleep peacefully. Like Rope, Leech is a passenger and not an official member of the crew. Like Rope, he feels responsible for the ship he helped build.

Leech is a handsome forty-year-old who, in his trademark heavy, round-rimmed glasses, looks a bit like the comedian Harold Lloyd. He worked on nonrigid airships during the war, earning the Air Force Medal for gallantry in 1919. He is a brilliant automobile mechanic, too, part of legendary British racer Malcolm Campbell’s engine team from 1921 to 1924.

After visiting the lounge earlier for a smoke with Irwin and Gent, Leech made a tour of the ship’s five engine cars. He returns at around 1:45 a.m. for another smoke and a drink. He sits alone now on a cushioned wicker settee against the wall in the sixteen-by-twelve-foot space with asbestos walls and ceiling, with his glass, ashtray, decanter, and soda siphon in front of him.

The image is arresting. A man alone in a small white room, engines droning and clacking somewhere beneath him, above him so many sleepers, in berths he cannot see. Though he doesn’t know the particulars, the airship that looms invisibly above him is coming up on the ancient town of Beauvais, France. She is running hard against a fifty mph wind at an elevation of twelve hundred feet.

According to later statements from one witness on the ground, “The wind was very violent and the rain was rather strong. The wind was coming in gusts, a tempest from the southwest, very strong, but not lasting. The wind was in heavy gusts and changing in direction.” Another witness said, “The wind was blowing in squall.” The air temperature is fifty degrees Fahrenheit.

R101 continues to labor forward, going so slowly—twenty mph over ground—that a witness on the ground thinks that she seems “in difficulty.” She has averaged a mere thirty-three mph over the 248 miles they have traveled since leaving Cardington. She is two and one-half hours behind schedule. Her crew will have to do much better if they are to make Lord Thomson’s state dinner in Ismailia.

Nor does Leech witness the change of watch, which happens on schedule at 2:00 a.m. Captain Irwin retires. Second Officer Maurice Steff takes command of the ship. He is the least experienced of R101’s officers. The chief coxswain is the handsome veteran George “Sky” Hunt, who supervises the rudder and elevator coxswains.

In the lounge, Leech, sitting peacefully, feels a massive shift in the unseen world around him. The movement is violent and sudden. In an instant everything in the lounge is moving, including Leech. He is thrown forward. He slides along the settee and comes up hard against the forward bulkhead along with his table, ashtray, glass, and other glasses and the soda siphon.

Because he is in a sealed chamber with no view on the outside world, he has no horizon lines, no landmarks, to tell him what is happening to the ship. But he can feel the world drop away. The airship is in a dive. He tries several times to get to his feet. He has the strong sense that, as he says later, “we must have dived a considerable distance.”

He finally manages to stand and realizes that the sealed container he is in has leveled out. The crashing sounds have stopped. He drags the table back into position, picks up the glasses and soda siphon, and places them back on the table. For a moment—it will not last long—everything again seems right in the world.

*

Minutes matter now. Seconds matter. In the wind-torn, rain-swollen night over Northern France, we can see only flashes. We can see only pieces of light and darkness. We can see only what the men see, the precious and lucky few.

Joe Binks, late for work and fortified by hot chocolate, hustles along the gangway toward the stern of the ship, traveling about 150 feet. He climbs through the hatch, then down the rope ladder, a perilous space between the dark hulk of the airship and the suspended engine nacelle where the wind exceeds sixty mph. A lost step or missed handhold and he is gone into the night, or perhaps into the propeller.

Though airships are known for being quiet and tranquil, the world inside R101’s cramped engine cars is anything but. The air is piston-pounding loud, hot, and smoky. Between the engine block and the wall of the car there is barely room to turn around.

Inside, Binks is kidded for his lateness by his fellow engine mechanic Arthur Bell, the man he is relieving, a veteran who has been in the airship service since 1919 and served on the ill-fated R33. Bell points to the engine chronometer, which reads 02:03 hours. Bell could be in bed by now. Minutes matter. Seconds matter. Though conversing is hard, the two men manage it anyway: they discuss engine temperature and pressure.

Binks has no idea that his late arrival has saved Arthur Bell’s life.

A minute or so later the ship pitches precipitously forward. The men can feel it. They know that R101 is in a steep dive. Thirty harrowing seconds later she levels. Inside the cramped, dim, noisy nacelle, Binks and Bell understand nothing. An order comes across the ship’s telegraph to slow the engines, for what possible reason is impossible to say. Bell barely has time to do this before he is thrown forward again, this time in a dive that lasts probably fifteen seconds.

But it is an excruciatingly long fifteen seconds. Time slows. Binks, who in his own description is looking out the door of the nacelle, begins to understand what is going to happen. The ship drops, and he sees nothing, nothing, as she continues to drop, nose at a terrifying downward angle of twenty degrees, plunging into the darkness of the unimaginable French countryside below.

He sees the ground come up and feels the airship crash into the earth. She hits nose down, an oddly nonviolent action—more of a massive crunch—followed by an explosion in the forward part of the ship so powerful that a pedestrian more than eight hundred feet away is blown off his feet and the sky is filled with burning debris, some of which lands two miles away.

The time is 2:09.

The aft engine car bumps along the ground for a short distance and lands in a world of fire. Flames rise through its collapsed floor, through the doorway; they encircle the engine and the fifteen-gallon gas tank for the starter engine—a point of weakness on the otherwise all-diesel airship. Fire is everywhere. Smoke fills the car, which has been jammed upward into the ship’s hull. Binks and Bell are trapped.

The ship drops, and he sees nothing, nothing, as she continues to drop, nose at a terrifying downward angle of twenty degrees, plunging into the darkness of the unimaginable French countryside below.

As they conclude simultaneously that they are going to be burned to death—”We gave ourselves up for lost,” according to Bell—somewhere above them in the inferno that used to be an airship a two-hundred-gallon water tank ruptures, sending a cascade of water over the engine car and drenching Binks and Bell. The waterfall has given them a way out. With wet rags over their faces, they jump clear, landing in rough grass on the edge of a wood. The world around them glows incandescent red.

From later photos of their engine car, smashed and burned and collapsed beyond recognition, its duralumin sheet metal sagging like wet paper, it is a miracle they escape at all. The sight of their burning, skeletal airship astounds and saddens them. Her cover is burned away, her gasbags gone, her entire “accommodation” section collapsed and burning furiously, girders glowing and collapsing, flames shooting up from fuel tanks and burning puddles of oil on the ground, minor explosions still taking place. They circle the ship, shouting, trying to find other survivors.

*

In the smoking lounge Harry Leech hears the bell of the engine telegraph, feels the ship dive a second time and then the surprisingly mild shock of impact. Two seconds later the explosion produces, in his words, “a blinding flash of fire” and then sends a “mass of flame” sweeping aft from the region of the control room, a massive whoosh as though a large pool of gasoline has been ignited. Leech watches this through the doorway, which has been sprung open. He is miraculously unharmed.

“Ironically,” he would say later, “the smoke room was the one place in the airship which gave a certain protection against fire. But I knew I was safe only for a time.” In the next second the upper passenger deck—the smoking lounge is on the first level, with the crew quarters, control room, and dining room—collapses on top of him, crashing down and settling on the backs of the settees, trapping Leech in a space three feet high that is filled with choking fumes and smoke. The flaming airship, its hydrogen/air combination burning at 3,713 degrees Fahrenheit, is collapsing around him.

He is aware of human sounds.

He hears “people screaming and moaning in the crew quarters and also from the upper passenger deck, which was then blazing.”

Only seconds have passed. Red fire is tearing through the airship, which has not yet fully settled to earth.

Leech tears a settee from the bulkhead, punches through the ultra-light faux-mahogany wall, and escapes the room. R101’s famous trompe l’oeil architecture and asbestos linings have saved him. He forces his way through the burning Cellon windows of the promenade and jumps, landing in a tree. He scrambles to the ground, walks away from the burning ship, and only then realizes that he is on fire.

In all only eight men emerge alive from the fiery destruction of His Majesty’s Airship R101.

His clothes are burning, scorching his neck. His hands are badly burned. Still, his first instincts are to search and rescue. He soon finds Binks, Bell, Victor Savory, an engineer from the port midships engine car, and Arthur Disley, the electrical manager and wireless operator. Disley is pinned and must be rescued. Leech crawls back into the burning ship, under red-hot girders and across pools of flaming oil, to drag him out. He saves Disley’s life.

Disley has his own tale to tell. He was dozing on his bed in the switch room when he became, as he says later, “conscious of the ship dipping a little, not more than it had done before, and this change of attitude seems to be corrected immediately.” He is drowsy, half-awake.

He is wrong. In his half-dream state he has mistaken the airship’s thirty-second dive for routine pitching. One imagines the same thing happening in the crew and passenger quarters: forty men nestled comfortably in their berths, fast asleep, opening their eyes and coming to consciousness for a moment. What was that? Nothing, the ship is level. Back to sleep. In seconds they will all die screaming in a fire fueled by 5.5 million cubic feet of hydrogen.

But Disley is lucky. He wakes himself up, and then a curious thing happens. George “Sky” Hunt, the chief coxswain, who is in charge of not only the elevator and rudder men and watch-keeping riggers but has general responsibility for the hull, cover, gasbags, gasbag wiring, ballast, and flight controls, walks into the switch room and announces in an oddly matter-of-fact way, “We are down, lads.” He then heads off in the direction of the crew quarters. The statement is curious because the airship is emphatically not down. She is airborne. She has leveled off.

Some unseen catastrophic event has happened, but there is no one to explain what it might be.

Disley stands—or rather tries to stand because R101 has just dropped into her second dive. He is thrown back onto his bed. He has the presence of mind to trip one of the electric field switches, shutting off some of the airship’s power. He is worried, correctly, about what sparks might do to all that hydrogen. He, too, experiences the crash as “more of a crunch than a violent impact.”

But it is followed, in his words, by a “first explosion immediately after the crash that was very violent.” The airship’s lights go out. Just how Arthur Disley went from the quiet comfort of the switch room to being pinned under a burning airship and suffering severe burns is not known. He does not know it himself.

In all only eight men emerge alive from the fiery destruction of His Majesty’s Airship R101. Four of them are engine mechanics, all working in cars outside the airship’s envelope: Binks and Bell from the aft nacelle, Victor Savory and Alfred Cook from the midships nacelles. Leech and Disley have different jobs but at the time of the crash are just a few feet from each other. The other two are riggers, men who patrol the inside of the ship’s envelope: Walter Radcliffe and Samuel Church. Both are grievously burned: Church dies on October 6, Radcliffe on October 8.

Which leaves six men alive from the fifty-four passengers and crew of R101.

______________________________

Excerpted from His Majesty’s Airship by S.C. Gwynne. Copyright © 2023 by Samuel C. Gwynne. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

S. C. Gwynne

S.C. Gwynne is the author of His Majesty's Airship: The Life and Tragic Death of the World's Largest Flying Machine, Hymns of the Republic, and the New York Times bestsellers Rebel Yell and Empire of the Summer Moon, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He spent most of his career as a journalist, including stints with Time as bureau chief, national correspondent, and senior editor, and with Texas Monthly as executive editor. He lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife.