When Marie Curie Was Almost Excluded From Winning the Nobel Prize

Liz Heinecke on the Curies' Rise to Fame and Their Ongoing Battle with Misogyny

In November of 1903, the Nobel Prize committee had announced that Marie and Pierre Curie, along with Henri Becquerel, had won the prestigious physics award for their work with radioactivity. The French, who were still licking open wounds from the anti-Semitic Dreyfus affair, were happy to have a less divisive topic of conversation. The Curies’ story, which featured love, suffering and a magic potion called radium, was a balm for the nation.

At the time, few people were familiar with the Nobel Prize, which had been established in 1895. Worth 70,000 gold francs to each winner, the prizes for Chemistry, Literature, Peace, Physics, and Physiology or Medicine were funded by the fortune contained in the will of Alfred Nobel, the Swedish inventor of dynamite. They were to be presented in recognition of scientific, academic, or cultural advances. Following Nobel’s death, the first prize was awarded in 1901, but it was the Curies who made the prize famous.

Marie was almost excluded from winning the award, simply because she was a woman. In 1902, a doctor on the Nobel committee named Charles Bouchard had nominated Marie for her work on radioactivity, along with Pierre and Henri Becquerel, but they were passed over that year. Then, in 1903, four more prestigious men on the committee nominated Pierre and Henri for their work with radioactive materials, omitting any mention of Marie.

Three of these four men were familiar enough with the Curies’ work to know perfectly well that it was Marie who had discovered radioactivity in pitchblende and single-handedly isolated radium. Despite this, they claimed that Pierre and Henri Becquerel had “worked together and separately to procure, with great difficulty, some decigrams of this precious material.” It was Marie’s worst nightmare come true.

When Pierre learned what had transpired, with Bouchard’s backing he forced the committee to add Marie’s name to the nomination and told them that he would not accept the prize unless Marie were included. She was still not treated as an equal, though, and when the prizes were awarded, Henri Becquerel was given 70,000 gold francs, while Marie and Pierre received a single sum of the same amount to share. Although she never complained, the experience made it crystal clear to Marie and everyone else that she was seen by many in her community as little more than a lab assistant, and that without Pierre as her advocate, she might have been a footnote in history.

Three of these four men were familiar enough with the Curies’ work to know perfectly well that it was Marie who had discovered radioactivity in pitchblende and single-handedly isolated radium.

Pierre, who had spent most of his career being ignored by the upper echelons of academia, found fame amusing at first, when French newspapers criticized the Sorbonne for their treatment of him and Marie. Journalists bemoaned the elitism of their most famous university, which was always eager to welcome wealthy and well-connected scientists but had completely ignored the Curies. When Pierre and Marie threatened to leave Paris in 1900, he’d been offered a slightly better job teaching medical students at the Sorbonne’s P.C.N. (Physics, Chemistry and Natural History) annex on rue Cuvier in a building across the street from the house where Henri Becquerel first discovered radioactivity. The position came with little influence and no lab space other than their tiny workroom, but the Curies needed money for their research, so he took the job and spent four years bicycling between the shed and the P.C.N.

Now, under public and government pressure, the Sorbonne had finally offered Pierre a physics chair, but once again no lab space came with the position, so he turned the offer down. All he and Marie really wanted was a better laboratory. The government tried offering him the medal of the Légion d’Honneur, but he declined the award, stating that he needed a laboratory, not a decoration.

At Marie’s urging, he finally persuaded the Sorbonne to offer him better laboratory space at the P.C.N., along with a promise to secure funding for more. Marie was made laboratory chief there but was offered no place on the faculty. Before the Curies could move from their shed into the new laboratory, the money from the Nobel Prize made it possible for him to quit his teaching job at the P.C.N.

As the Curies’ star rose, so did the popularity of radium. In addition to helping scientists unravel the mysteries of the universe, the beautiful element had healing properties and showed promise for curing cancer and other previously untreatable conditions. In the name of science and public interest, the Curies shared their method for chemically extracting radium from pitchblende with academia and industry, and the first radium factories were constructed. Without uranium ore, there was no radium, so the race was on to procure pitchblende mining waste. In France, a rumor had begun to circulate that Thomas Edison was buying up every bag of pitchblende that he could get his hands on.

Pierre, who had spent most of his career being ignored by the upper echelons of academia, found fame amusing at first, when French newspapers criticized the Sorbonne for their treatment of him and Marie.

Verbal battles raged as people argued about whether a woman could be a good wife and mother while working outside the home. When certain reporters arrived at the Curie residence to find Marie away at the lab, they called her a bad mother. It was difficult for traditionalists to imagine a husband and wife working side by side toward a common dream, although the creative consciousness was fascinated by the idea of science mingled with love. The strange circumstances of Marie and Pierre’s relationship allowed writers to transform the shabby reality of their shed laboratory into a romantic radium-lit atmosphere, shrouded in mysterious vapors. Camille Flammarion wrote: “I see in my imagination, She and He, in the age of dreams, both impoverished but rich in hope and seeking I know not what magic talisman to cure the world of its worries . . . And one day, at the bottom of their crucible—joy intense and unforgettable—they find the treasure they were searching for.”

Pierre Curie was celebrated for being a native son of France, and Marie was adopted by the French public as one of their own, her Polish heritage ignored or conveniently forgotten. Mountains of mail from admirers flooded their house. Everyone suddenly wanted a piece of their time, attention or money. They were tirelessly pursued by journalists, who appeared at their front door day and night. At first, they patiently responded to the endless river of questions, but soon they were drained of answers. It was exhausting and distracting for the introverted couple, who just wanted to focus on their work.

__________________________________

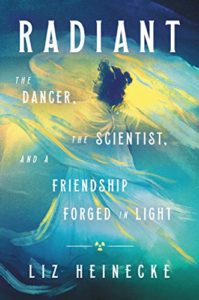

Excerpted from Radiant: The Dancer, The Scientist, and a Friendship Forged in Light by Liz Heinecke. Copyright © 2021 by Liz Lee Heinecke. Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Liz Heinecke

Liz Heinecke worked as an academic molecular biology researcher before starting her online educational platform KitchenPantryScientist.com. She has written seven books teaching kids (and their parents) how to perform simple science experiments at home, and is a regular fixture on local TV morning shows including CBS and ABC. She lives in Minneapolis, MN.