When Male Authors Write Male Violence

Philippa Snow on Ryu Murakami’s Novel Piercing

In a 1994 Guardian review of Ryu Murakami’s Piercing, the filmmaker and writer Chris Petit claimed that there was no more obvious influence on the novel than the American auteur David Lynch. “Piercing is a Japanese extension of Lynch’s world,” Petit suggested: “Surreal, sexually anguished, highly neurotic, both knowing and naive.” This is, I think, an accurate observation; I would add that one of the most Lynchian traits the book displays is its depiction of the sexes, in a very simple and old-fashioned split of “male” and “female,” as being engaged in a form of psychosexual warfare with each other, each side at once terrified and insane with desire.

The films of David Lynch, of course, are not the only form of media in which a man and a woman—serially misunderstanding each other, warily circling, unsure whether they are enemies or lovers—slip into a folie à deux-style delusion: think of romance novels, or of the romantic comedy. True, Murakami’s novel begins with a man imagining dispatching his own infant with an ice pick, and it ends not too long after somebody has tried to gouge out someone else’s eye with a can opener, and as such, to characterize it as a romance might be tantamount to madness.

Still, I think there is an argument to be made that the author is deliberately skewering the tropes of romantic love as they appear in books and cinema, and that actually, he does it well enough that Piercing manages to say more about the romance novel’s bizarre characterization of the relationships between men and women, in bed and in marriage and in the domestic realm, than most actual satires of the genre I can think of.

In the opening pages of the novel, we meet Kawashima Masayuki, a married man with a tiny baby daughter who is—as a great number of married men with brand-new babies tend to be, in my experience—undergoing a major crisis. His wife Yoko, a domestic goddess who has given up her job with a major manufacturer of baked goods in order to teach other women to make pastry, is perfect to the point of being cartoonish. She is patient, kind, and beautiful; she smells of freshly baking bread, and we imagine that her hair must look immaculate. “He couldn’t believe,” Kawashima thinks, “he’d managed to meet, fall in love with, and actually marry a woman like this.”

Marriage, he suggests, has changed him, mostly for the better, and the nightmares and odd fits of violent rage that used to rise up in him as a result of his horribly traumatic early life have not affected him in years. “Until,” he admits gravely, hovering over his daughter’s crib, “ten days ago.” It transpires that in his youth, he stabbed a former girlfriend in the stomach with an ice-pick, and the urges that drove him to do so are resurfacing after a period of dormancy now that the novelty of his wife is wearing thin. (Show me a beautiful woman who bakes perfect bread, to paraphrase the saying, and I’ll show you a man who’s tired of eating perfect freshly baked bread every day.)

Isn’t the joke at least a little bit that men suffering midlife crises, even deranged psychopaths, are essentially all the same?

When Murakami sums up Kawashima’s personality by noting his preference for the colder outdoor weather over the welcoming interior of his house—in heated rooms, Kawashima thinks, “he often felt the outlines of his body, the border between him and the external world, grow disturbingly fuzzy”—he also suggests the sensation of being one half of a marriage and one participant in a family unit, the loss of individual identity that can be both comforting and unnerving.

The problem, as Kawashima sees it, is that the mysterious voices that instruct him to do evil tell him that his baby daughter ought to be his latest target. (In a bit of gallows humor, they have settled on an ice pick as the weapon partly because of his former crime, but also partly because when Yoko was pregnant, she and Kawashima watched Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct.)

Since being the father of a daughter is not enough to keep Kawashima from fantasizing about killing and injuring women, he resolves to hire a sex worker instead, then murder her in a hotel room. That the sex worker is also someone’s daughter does not seem to occur to him, but that fact will become an important plot point later in the novel—Murakami is a firm believer in the credo about parents so famously laid out in the ubiquitous Larkin poem, and if Piercing is a kind of allegory about the exciting mutual destructiveness that often characterises relations between men and women in romance, it also one about the terrible influence our parents have on our desires.

Faking a business trip, like a guy in a bad movie who is planning an affair, Kawashima meticulously plans out the murder in a notebook, eventually deciding that a girl from an agency that specializes in S&M would suit his purposes. The agency, in an act of kismet that will ultimately end in something like a meet-cute—a meet-squalid, maybe, to use a phrase coined by Thomas Pynchon in Inherent Vice—sends a pretty maniac with a history of self-injurious violence named Chiaki. Hand, meet glove; knife, meet scabbard. It is destiny, a pairing as impossibly ideal as any in the movies.

What follows is a screwball farce with added gore: just as Kawashima gears up for the promised deed, Chiaki excuses herself to the bathroom and, entering a fugue state, begins stabbing herself furiously in the thigh with scissors. “She wants me here, but not too close,” Kawashima realizes, after he has recovered from the shock of catching her. “She panics if I approach, and she panics if I try to leave.” A violent game of cat and mouse begins, each party chasing their own insane goal. “He’s somebody very special, a very important person,” Chiaki concludes as Kawashima takes her to the hospital. “It’s not so easy to meet people like that.” “She’s one of us,” the voice in Kawashima’s head observes, admiringly, as he debates whether or not to follow through with her eventual murder once she’s been patched up and discharged. “A kindred spirit.” “His face was a complete mess,” Chiaki thinks tenderly later, as they take a cab to her apartment, “and yet it was also the most adorable thing she’d ever seen. She had a sudden urge to hit that face. Not just give him a little slap on the cheek but slug him as hard as she could, with her fist or a bottle or a wrench or something, right in the eye.”

Sometimes, love is a thriller, and occasionally it is a horror story, extreme and guiltily pleasurable and utterly devoid of sanity or sense.

Neither Kawashima nor Chiaki is what one would typically describe as a well-rounded character, in the sense that they have no obvious attributes other than those that power the plot: Kawashima is an outwardly conformist jobsworth whose childhood abuse has shaped him into a dissociative sadist, and Chiaki is a quirky optimist who still believes in love in spite of the fact that—wouldn’t you know it—her childhood abuse has shaped her into a dissociative masochist. They have this simplicity in common with the heroes and heroines of paperback romance novels, who tend to exist solely to be pressed together like dolls or puzzle pieces by the author, carrying us from one explosive sexual or romantic (or, in this case, violent) set piece to the next.

I understand why men writing or otherwise creating narratives about misogynistic violence are regarded with suspicion, but the uncomfortable truth is that it is sometimes male artists who make the best and most exposing work about men being complete pieces of shit. Strip Piercing of its grand guignol, ecstatic violence, simplify the plot, and you have the story of a man having a midlife crisis, regretting his fatherhood, seeing his wife as a compliant domestic cipher, setting out to realize his fantasies with a sex worker—then discovering that she is a manic pixie nightmare girl sent by fate to mirror his extremely singular desires.

Isn’t this almost rote enough for Hollywood? Isn’t the joke at least a little bit that men suffering midlife crises, even deranged psychopaths, are essentially all the same? That Chiaki sees her would-be killer as her soulmate, too, becomes less absurd when one considers, for example, Fifty Shades of Grey, a book in which the billionaire romantic hero woos his heroine by turning up at the hardware store where she works to purchase rope and zip ties, making her sign an exclusive sexual contract, monitoring both her diet and her birth control, and forbidding her from socializing freely with male peers.

“To be able to choose your own pain—it’s a little scary,” Chiaki tells herself, “but it’s wonderful, too.” As it happens, she is considering getting a tattoo when this thought pops into her head, but the line is such an ideal description of the self-harm inherent in a certain kind of love—the eagerness to risk complete annihilation for the sake of one’s desires, walking willingly into the slavering jaws of the beast—that it works as a key for a reading of Piercing as a satire of heterosexuality, too. Love is not always a romance novel; sometimes, love is a thriller, and occasionally it is a horror story, extreme and guiltily pleasurable and utterly devoid of sanity or sense.

_____________________________________

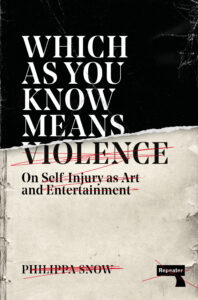

Which As You Know Means Violence: On Self-Injury as Art and Entertainment by Philippa Snow is available from Repeater Books.

Philippa Snow

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norwich. Her reviews and essays have appeared in publications including Artforum, The Los Angeles Review of Books, ArtReview, Frieze, The White Review, Vogue, The New Statesman, The TLS, and The New Republic. She was shortlisted for the 2020 Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize.