When Love Means Letting Go: Jiordan Castle on Navigating a Tumultuous Relationship With Her Father

“I had a choice: to keep my dad and lose my way or preserve us like a handprint in cement.”

Before I met my husband, Jerrod, I only thought about marriage in the most abstract terms, like owning a Jet Ski or using credit card points. I did, however, think about love. I had been in love when I was eighteen, but after that, I bided my time with a series of nexts: the next phone call, the next first kiss, the next dinner date, the next last look before starting another monthlong relationship. Until Jerrod, I had never introduced a significant other to my dad. No one loomed or lasted like this quiet, clever, left-handed stranger who came into my life when it was fraying at the edges.

We found each other on Craigslist as last-second roommates in San Francisco; I was twenty-two and he was twenty-five. I had left New York City three years earlier for a new start, a second chance at college, and he had just come from there for a new job south of the city. After exchanging emails and texts, we met on a Tuesday after work. He was clean-shaven and wearing all black, save for a white T-shirt that said Dad Punchers, the name of a band. I watched him round the corner and enter the pizza shop like a curved bullet. I felt an urgency then, a nameless want, hidden even from myself.

It took months for both of us to realize that our roommates-to-something-more relationship wasn’t a fluke of timing and proximity. I bought him a black button-down shirt for his birthday. For the holidays, he bought me a Transformer—Megatron, specifically—because I’d always wanted one. Though we hadn’t defined our relationship, we became a domestic team almost overnight. I saw the small, sometimes unspoken ways in which Jerrod knew and appreciated who I was. I found myself collecting details about him, as if the simple act of amassing them would keep him in my life. He’s the kind of person who likes public transit maps and researches every aspect of a thing before he commits to it, even if that thing is a pair of slippers. I was fascinated by the way he viewed life through a microscope of his own making. I knew I loved him before we ever made it official.

*

A few years later we moved back to New York City. At least a small part of me wanted a do-over, a middle finger to the past—and to the story I told myself about myself: that being from Long Island and moving only as far as “the city” was a personal failure. When I moved to San Francisco, I wanted a world away from the one that had made me. In that world, my dad was always on the verge of a big break or a breakdown. I had navigated closed doors, screaming matches, and depressive episodes. Like any family, mine had its deceptions and resentments, alongside deep, primitive love—the kind that doesn’t make sense to anyone but the people in it. The five of us clicked and clashed, trying as we might to understand one another. We maintained our ecosystem until it eventually eroded.

I pretended for years—long enough to fool myself. I was watching for a sign from the universe instead of watching my dad.

I told myself it wasn’t New York’s fault, though that didn’t stop me from resenting it. With Jerrod, though, I felt I could return to my home state.

We adopted a dog, and we packed tiny, worn-and-torn apartments with art and video games and books. I liked moving forward in time and space, renewing the lease on our life together. But having returned to New York, my mind wandered to the black box of my youth—to the years my dad spent in prison when I was a young teenager. That period lived in an unmarked but shallow grave in my memory. I found myself digging around, unearthing things without meaning to. I had nightmares, I had questions. I learned to live with both, or I tricked myself into thinking I had.

I couldn’t make sense of my own rage, my hurt, my slow panic when Orange Is the New Black or Shawshank Redemption came up in conversation. All the wordless things I packed up and shelved in order to function, and in order to keep my dad in my life. It was never a question of love—whether I loved my dad enough to keep him, or if he loved me enough to stay—but rather a conscious avoidance of discussing the most painful parts of the past. If we didn’t look back, our history couldn’t hurt us.

But my subconscious knew better. I saw a therapist for a couple of months when I was twenty. He drank from Starbucks’s red holiday cups and always told me exactly what he thought, which was usually to stop dating whoever I was dating. I remember him as one of the first men I trusted, even if only because he told me the truth, of which there was only ever one version.

I talked about my dad’s suicide attempt, his time in prison for financial crimes, and how fractured my family became—the thorny estrangements and secrets, some of which were polite and necessary and some of which were mean and stupid. Family members stopped talking to each other, and I couldn’t talk to some about others; each person became a shadow to someone else. There were family members I never saw again after my dad went to prison. At the time, though, I was mostly focused on getting through the day.

What could I say to my therapist about my parents getting divorced while my dad was incarcerated? I remember my dad received the papers on his birthday. That detail sticks to my rib cage, much like the fact that I didn’t invite him to my high school graduation after he got out; I didn’t want my parents in the same place. I had managed to keep them from seeing each other since his release. I went so far as to have my mom drop me off a few blocks away when I met my dad somewhere for dinner. Who was I protecting by keeping them apart? I think I never trusted them with each other again—or with me as their messenger.

But I decided this was all past tense. All these things were younger Jiordan’s problem, not mine. I couldn’t see myself in myself. After seven sessions, my insurance ran out, and I decided I would rather put a lid on it than work through it—the growing “it” that threatened to upend my life. Insurance didn’t grant more sessions and I didn’t return to therapy. I looked outward. I kept pretending my dad could never, would never, do anything that would get him sent back to prison. I pretended for years—long enough to fool myself. I was watching for a sign from the universe instead of watching my dad.

*

Most people in the United States know that we incarcerate an overwhelming number of people at the federal and state levels—nearly two million. But what isn’t talked about as readily, or as simply, is recidivism. The National Institute of Justice defines recidivism as “a person’s relapse into criminal behavior, often after the person receives sanctions or undergoes intervention for a previous crime.” Many formerly incarcerated people become reincarcerated due to a variety of factors: violations of supervised release, parole, or probation; new arrests and convictions. Not only is it easy to become incarcerated, but reincarceration is likely for many prisoners. Two out of three former prisoners are rearrested and more than fifty percent are incarcerated again within three years of their release.

When I say the phrase “justice system,” it always has air quotes. I believe the present-day system serves to punish, not rehabilitate.

If you survive incarceration, you’re marked on the outside. It’s more difficult for people with a criminal record to acquire the basics, like a job or an apartment. And that doesn’t include other necessities or joys, like voting or driving. Everything is harder, and it becomes exponentially harder the longer you’re in.

I remember how my dad handled a car a few years after he was first released. How long he sat at an intersection before making the turn, a palpable anxiety hovering just above the pedal. He had never slept normally since I’d known him, or within normal hours, but sleep seemed more elusive and stressful. He told me things about his time in prison that kept me up at night; I imagined his own dreams tended toward darkness. He was incarcerated for a handful of years and, still, the transition back was complicated. After prison, home is not necessarily what you remember; it’s what you can remake.

My dad has always been an adventurous eater, and the lack of variety in prison, let alone the lack of nutritional value, is bleak. Prison diets are starch heavy. Our meals at restaurants after his release went on for hours—guacamole, fajitas, tacos, flan. What I sometimes considered excessive, especially if I said I was full before the dessert course, was mainly intended to extend our time together. But I also think it was in an effort to experience everything, however ordinary. Ordinary things become precious once they’ve been taken from you. This is especially true if they can easily be taken from you again.

My dad had all the makings of an American post-prison success story, released with a one-way ticket back to society: He was white, he was educated, he had certain safety nets. But my dad was an entrepreneur. He had big ideas, combined with a brain chemistry that played tricks on his emotions and his logic.

When I was growing up in a mostly affluent suburb on Long Island, status mattered a lot to my dad—big house, nice things, and a beautiful family. That standard of beauty equated to thinness, and during one of the worst manic episodes I remember— shortly before my dad went to prison the first time—he shouted that if he had fat daughters, he would kill himself. He had seen me eating a piece of cake for breakfast. He said this during a boom of fad dieting in America, when trans fats were the enemy and people were eating cereal for each meal in an attempt to cut calories. When he apologized, I knew it was sincere, though I could never unhear the threat he’d yelled at full volume.

I was in my late twenties when the warning signs appeared again—his mental health was correlated with his business aspirations, and both had begun to deteriorate—but it was already too late. He had gotten himself into trouble again and there was no exit plan. It was inevitable now, he was caught. Financial trouble. Legal trouble. The mounting evidence must have taken months or a year to accrue, maybe more, but when he called and explained, it felt instantaneous, like a car crash.

And then he went missing. I waited. I knew. He tried to commit suicide again, at the same hotel chain. This time, the police called me. I was the adult in the room, only the room was a supermarket parking lot and I was looking at my sister, which did more for me than any prayer.

My dad. The person who played guitar and piano and made tortellini with pink sauce and hung wind chimes from the back door. The person who could hit the high notes singing along to Aretha Franklin in the car, who gave gifts like smooth hematite stones and wooden bangles, had become a career criminal. It was a surprise to both of us, for a time. A misunderstanding. Except that I was beginning to understand.

*

I went on a kind of autopilot leading up to the sentencing. At the time, I was getting my MFA in poetry and working full time. Most nights, I cried watching bad TV on the couch after work and class. I developed scalp psoriasis and heartburn. I didn’t want to die, but I didn’t feel like I was living. I was losing grip on the life I had been building since I moved to San Francisco years earlier. I had wanted to hit reset—a new beginning. Yet here I was, slamming the button, and somehow back in the life I thought I’d left behind.

Except this time, there was Jerrod. He filled in the gaps. He did the laundry, he dealt with dinner, he vacuumed. He propped me up, literally, on the nights when I felt the weight of all my disparate selves. He had always gotten along with my dad the few times we shared meals or visited his house. But he had also made it clear that he would support me in whatever decisions I made regarding my dad, even when I felt powerless to make any decision at all. The offer never expired, and he never seemed to grow frustrated as I went back and forth with myself. He just stayed. When I felt emptied of everything, it was his unwavering support that served as my own proof of life.

When the judge handed down the sentence, I sat beside Jerrod on the bench and watched my dad’s back. I find it difficult to describe the love I felt then and still feel now. Whether my dad is, was, or became a criminal is not the point. Even that word, criminal, rings hollow to me. It only means something if you’re the judge, jury, or victim. I’ve played each of those parts, at times earnestly and at times bitterly, but I can only ever really be his daughter. That comes with heartache, but it also comes with a great deal of resolution. Resurrection, even.

*

In the story I used to tell about my dad and me, there was a clear before and after. Prison not as the sand but as the hourglass itself, built to shatter. He was a different person after prison the first time. I was too. I was afraid to get too close, of becoming stuck inside my depression or mired in a time and place I’d rather forget. I preferred looking toward the future, in which I imagined more autonomy for myself. Unfortunately, that meant relegating much of my childhood to the deep recesses of my memory.

Things weren’t always hard. There was happiness. Laughter. Excitement. Mystery. But to that end, near-constant chaos. That was not how I wanted to live as an adult, though I knew how to do it.

My adult life was different, softer at the edges. Being with Jerrod felt like having the creature comforts of being alone without loneliness. The disquiet and anxiety I lived with moved to a higher shelf in my mind and became increasingly difficult to reach. When I opened the door to our apartment, I felt full. I had a partner. I fell apprehensively, but finally, into home.

Whether it was selfishness or me finally telling myself the truth about what I could stand, what I was willing to give and take, I knew what I needed to do. Or rather, what I needed to let go of.

*

When I entered the visiting room at the prison, I knew it might be the last time I saw him. On some level, in some universe only I had the keys to, this was already the end. I had choices, priorities, and even dreams I didn’t have as a teenager. I knew my dad didn’t particularly want Jerrod to see him like this, and I didn’t want Jerrod to see any of us like this, so he waited in the car outside. What I didn’t know is that while I was inside, thinking about an ending, Jerrod was buying me an engagement ring over the phone. After a great deal of research, he had found an estate jeweler in San Francisco. He chose a 1940s marvel of diamonds and rubies—a bright, bold ring. One that was built not only to last, but to shine.

I thought of Jerrod while I waited for my dad to join me in the row of plastic chairs. I thought about how good it would feel to sit on the couch with our dog at the end of all this, what movie we would watch. Every imagined glimpse of the blissfully mundane evening ahead was a promise: if I could see the future, I could get myself there.

When my dad came out, he wore a hunter-green jumpsuit that was almost stylish. It was rough against my cheek as we hugged. I watched the other prisoners and their families, the kids’ corner with toys and a TV, my head full of static. Everything a high-pitched ringing, even the crinkle of bags of chips. I saw people take turns at the microwave, heating sandwiches and burgers in plastic packaging and squeezing condiment packets onto paper plates. At some point, I bought a cheeseburger for my dad with my quarters and prepared it, just as I had many years earlier. The memory made me feel even more outside my body. The shadow of my younger self and me, going through the motions, neither of us remembering to breathe.

He introduced me to another prisoner about his age, whose third wife was there visiting. An expression I couldn’t place passed over her face when she looked at me. Like sadness, but sheepish. She nodded at the ground when she said hello, as if we were there for different reasons. Maybe we were. The walls were high, painted a kind of gray-green undeserving of its own shade. If there was a day from which I couldn’t return, a point at which I knew I wanted—deserved—another life, this was it. This woman in the row beside me, the decades like a jagged line between us. I thought of the many years between the girl I was when the threat of prison first emerged and me now. I could see myself in my dad’s basement office, tugging at the loose button of an armchair, listening to a monologue I knew well: all the things he did for us and whether he should kill himself. An impossible hypothetical lodged in my throat. I wanted to save him at the expense of so much else.

For many years I thought letting go meant giving up. But really, it was like finding myself in a field of balloons, thousands of them bobbing close to the ground, all tied to a single tree.

I noticed a young girl coming out of the bathroom near the guards’ desk. I watched her as my dad talked to the prisoner and his wife. The girl looked so uncertain, her eyes darting around and finally settling on the ground as she walked back to whoever she was visiting. She couldn’t have been older than twelve. It was like slipping into a daydream, slowly realizing I had been that young once. I imagined myself older because I had to be. Did she have to be?

It took seeing it, or projecting it, on someone else to wake me up. I knew I wasn’t going to be back next month, next year, or in ten years. I was never going to return to this room. I was seeing my dad as if through a telescope, his blue eyes like new moons.

I felt like a traitor. I felt like a sucker. I felt the seconds slipping away from me. I was a good daughter to the extent that I could be trusted to show up, to listen, to empathize, to forgive. But what I couldn’t do was accept.

To accept this new reality and my implied role in it ran counter to the person I was becoming: a person I liked, a person I could respect. Somewhere inside me, I wanted to rejoin the world of the living. I wanted to show up, to listen, to empathize, to forgive—myself. It broke my heart as we sat there sharing a bag of Cheetos. Love was not enough, and I had reached an end without knowing it existed.

*

When Jerrod proposed to me a month later, I didn’t suspect a thing. We liked to surprise each other with dinner destinations, activities, and small gifts. It was our sixth anniversary, and he carried the ring in a slim, backlit black box in his suit jacket through dinner at a hotel on Madison Square Park. Afterward, he said we should go up to the roof for a view of the city. But he took me to a suite, which I thought we’d somehow entered by mistake, where he got down on one knee and asked if I would marry him. Many people I’ve spoken to who were also surprised by a marriage proposal seem to have experienced it similarly: It was a blur, I couldn’t believe it even as it was happening, the moment went by fast and slow. The question itself, the bright light of the box, and the ethereal sparkle of the ring stunned me. But I think what stunned me more was how easy it was to say yes, how permanent a fixture Jerrod had become in my life, of my life. To me, his question was rhetorical. I had always been living in the direction of this particular yes.

It’s not that Jerrod held my hand during my dad’s prison sentencing, or that he took me out to get a chicken salad sandwich when we arrived home that afternoon. It’s not that he rented a car and drove me to prison to see him that first and final time weeks later, or that he waited in the parking lot for hours even though he had to use the bathroom—badly.

It’s that I never doubted he would do any of these things. It’s that when I came out of the prison and asked why he hadn’t left to find a bathroom, I knew the answer before he told me; he didn’t want me to walk outside and find myself alone. It’s that I was in love with someone who knew who I was, and who wanted me to live.

Life is long and short and full of loss. But there are moments of love so staggering, so specifically yours, you can’t help but feel you’re witnessing a miracle. To someone, you are a miracle. Jerrod is mine.

When I said yes to his proposal, I found myself saying no to a life that taught me to make myself smaller, malleable to a fault. It didn’t happen overnight; in the month that followed our engagement, I didn’t answer a call, I didn’t open a letter. I told my dad’s wife I needed a break. Really, it was a breakthrough. I disappeared cruelly from my father’s life and reappeared somewhere else, as someone new.

It was only then that I began learning who that was, who I had the potential to be if I let myself live differently. Someone not so beholden to my dad’s every emotion on the phone, mired in guilt and rage that manifested as a depressed, distracted daughter. Someone who could call adolescence what it was: a series of years marked more by pain than by peace. Someone who understood that even the best intentions didn’t negate the damage my dad had done—his screaming fits, his crying jags, the work I did to shape-shift into what he needed me to be.

For many years I thought letting go meant giving up. But really, it was like finding myself in a field of balloons, thousands of them bobbing close to the ground, all tied to a single tree. The imperative was clear: I needed to release them. I knew the process would never end; there are just too many balloons. But I feel lighter each time I let one go.

In the months that followed, I looked at my reflection in the mirror and saw a friend there. Someone I could respect, protect, and cherish. When I married Jerrod, I did so with every version of myself. There is the child who loved my dad fiercely, who ate the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches he made with hamburger buns and listened at every closed door. There is the teen who felt she was never good enough for herself or anyone else but wrote her way through. And the adult, who fought until the only thing left to do was submit—to time, to the truth, to the primal knowledge of what it takes to not only survive in the world but to actually live in it.

This is a goodbye I carry with me like a wilted flower, one I can’t relinquish to the earth or bring back from the dead. Some goodbyes are ugly, hopeless things. This one was. Because there was a time before all this, a time full of light. I see it in flashes, like the sun through tree branches. We ate egg rolls, we made snow angels. We had a life together and we lived it. It’s in the rearview, growing smaller. It’s not gone. I had a choice: to keep my dad and lose my way or preserve us like a handprint in cement. It’s not with pride that I chose myself, but love.

__________________________________

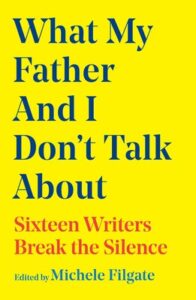

“In the Direction of Yes” by Jiordan Castle appears in What My Father and I Don’t Talk About: Sixteen Writers Break the Silence, edited by Michele Filgate. Copyright © 2025. Available from Simon & Schuster.

Jiordan Castle

Jiordan Castle is the author of Disappearing Act, a memoir in verse. Her poetry and prose appear in The New Yorker, The Millions, The Rumpus, and elsewhere, including the anthologies Best New Poets and What My Father and I Don’t Talk About. Originally from New York, she lives in Philadelphia with her husband and their dog.