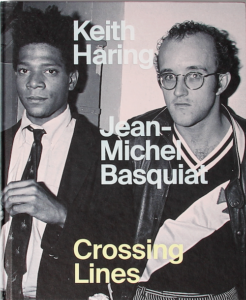

When Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat Took the 1980s NYC Art Scene by Storm

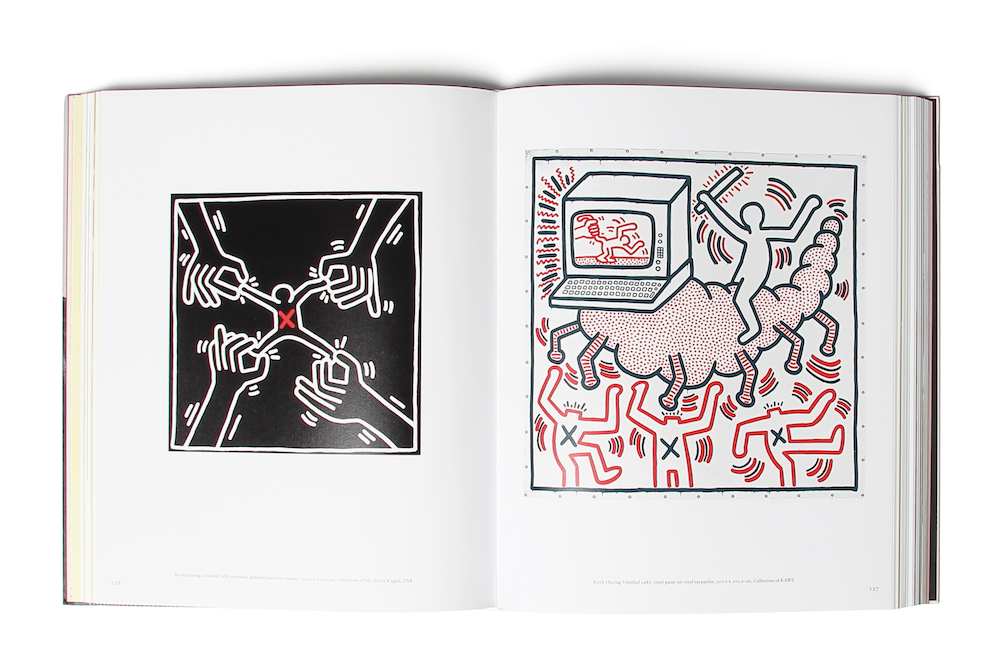

Dieter Buchhart on Two Icons of the American Art World

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat took the art scene of the 1980s by storm: first New York, then Europe, ultimately Japan and the rest of the world. In their works, saturated with signs, figures and words, the age found its symbols. But even 30 years after their all-too-early deaths, their postmodern, political line is stronger than ever. As predecessors of the copy-and-paste internet and post-internet society, they resonate with today’s youth culture. Their art inspires the very youngest as well as millennials and the generations before that. With their collaged spaces of knowledge, Basquiat’s works today command higher prices than the work of any other American artist, while Haring, with his image-words, could be seen to have contributed to the founding of our “emoji culture,” in which symbols have become a universal language.

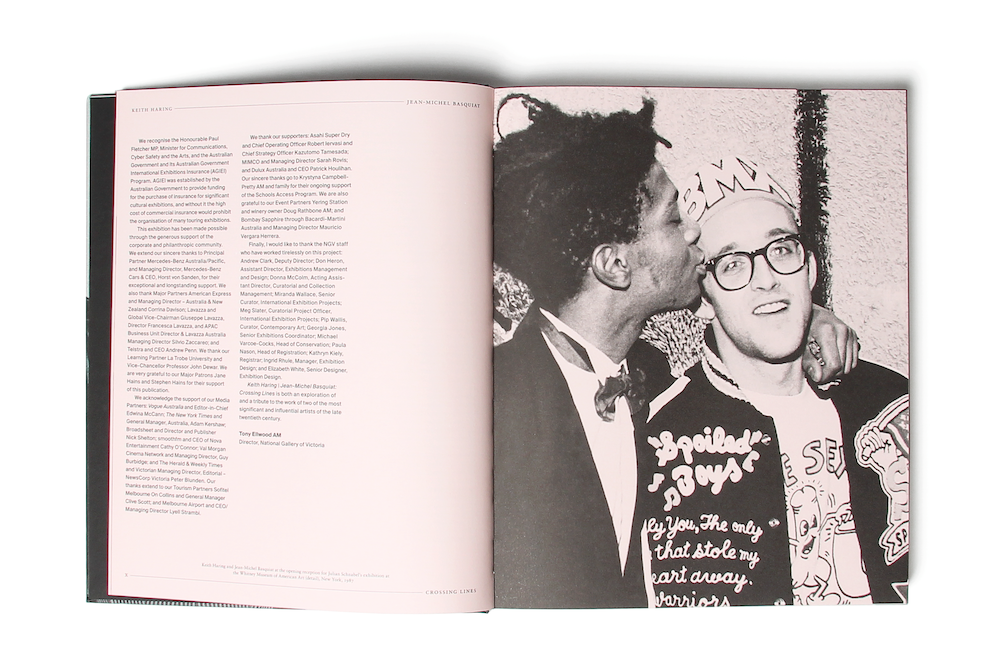

After numerous comprehensive retrospectives over the past decade honoring both artists and changing our perspectives on them, it seems important to take a look at these two pioneers together. Not only did they work at the same time in downtown Manhattan, but their personal and professional paths often crossed. Against the backdrop of this shared world, how can we describe the relationship between them? What are the similarities and differences between their work? And why has the significance of their art so drastically increased over the past decade? Now is the time to reveal the points of intersection in the two artists’ lives, work, and political perspectives.

Haring, born on May 4, 1958, was two-and- a-half years older than Basquiat, who was born on December 22, 1960. When he began attending the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in downtown Manhattan, Haring had already encountered Basquiat’s poetic, conceptual graffiti. As of 1977, Basquiat and street artist Al Diaz had already made a name for themselves under the pseudonym SAMO©, with concrete poetry like ‘SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS AND GONZOIDS …’ or ‘SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVΞ 2 “PLAYING ART” WITH “RADICAL? CHIC” SECT ON DADDY‘$ FUNDS ….’ Impressed by their concrete poetry, Haring paid homage to SAMO© in an early work from 1979. Years later, in 1985, Haring looked back over his artistic beginnings:

A few years back, there were a lot of things in New York that influenced me: graffiti writers, and street artists. People like Jenny Holzer, who took propaganda-like texts onto the streets, which aroused the public curiosity. Samo, who used the whole of downtown Manhattan as his field of operation, was the first to write a sort of literary graffiti. He added a kind of message to his name which conveyed an impression of poetry: statements criticizing culture, society, and people themselves. Since they were much more than ordinary graffiti, they opened up new vistas to me.

Haring encountered Basquiat during his time at SVA, as he remembered in the spring of 1981:

The School of Visual Arts was … actually where I met Samo (Jean-Michel Basquiat) for the first time. I let him into school without knowing who he was—because he was having troubles getting past a security guard at the front. I walked him in, and then later on I saw all this graffiti and found out he was the one who had done it … some of his best stuff was in the School of Visual Arts—because he was at his peak … He had things like ‘Samo as an attitude towards playing art’ or ‘Samo as Vincent van Gogh’ or ‘They made you a second-class citizen’… I had looked up to him for a while before I saw him, because I had been going to the Mudd Club. The whole route from the East Village to the Mudd was covered with [tags].

After the two artists became acquainted with one another, they became fast friends, despite the fact that they circulated in two different artistic circles: Basquiat was separating himself from the graffiti scene, while Haring was embracing it; Haring had formal training, while Basquiat had none. Artist and mutual friend Kenny Scharf described their close association:

I met Jean-Michel when I was 19 and he was probably 17, and Keith was a year older. And even though we were still young we definitely knew that there was something really exciting going on, and we were immersed in art; even though our styles were so different we definitely connected, and I got a lot from them … which is a kind of a competitiveness with people you think are really great, and you look up to, but you are still on the same level. So it created a tension that I thought was very healthy and exciting

… I never felt particularly part of a New York ‘group’ or a New York ‘thing’, I always felt a little individual … The only thing I felt I belonged to was maybe the threesome: Keith, Jean-Michel, and me, but that was not stylistic. The three of us definitely rejected the elitist art of the time, and that’s where we really had a bond.

After The Village Voice unveiled the secret of the identity of SAMO© on December 11, 1978, Diaz and Basquiat soon announced the end of their collaboration by spraying ‘SAMO© IS DΞAD’ on building walls. Haring then exhibited Basquiat’s works—the first time he did this—on May 29, 1980, at Club 57 in the group show he organized, the Club 57 Invitational, the next year presenting Flats Fix, 1981 in the Lower Manhattan Drawing Show, which he curated, at the Mudd Club from February 22 until March 15. During these years, Haring and Basquiat had their first more comprehensive exhibitions, both in alternative spaces as well as more established venues.

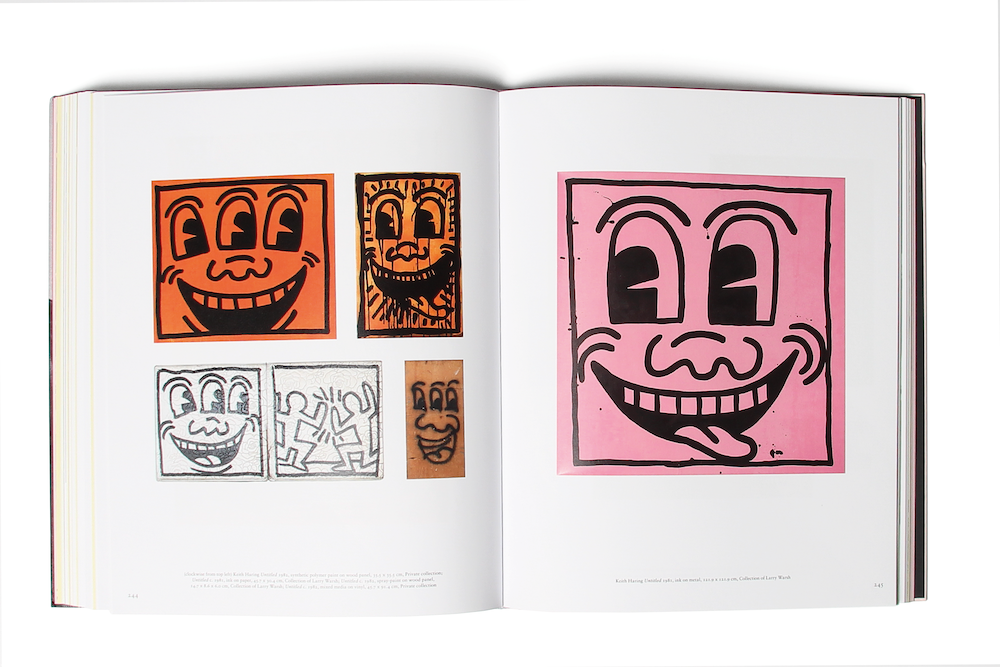

The two attracted great attention in the art world with their participation in the Times Square Show in June 1980 and then the New York/New Wave exhibition at the then P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center in February 1981, in particular. On October 30, 1981, Annina Nosei opened the exhibition Public Address, in which the influential gallerist showed works by both artists along with works by artists like Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. Nosei dedicated the entire rear space to Basquiat’s standing black male power figures created on wooden doors, including Irony of a Negro Policeman, 1981. In December 1981, the legendary essay “The radiant child” by Rene Ricard followed, which explored Basquiat and Haring in detail, the author noting that “Jean-Michel’s [works] don’t look like the others.” Basquiat “evolved a vocabulary, and so in his way has Keith Haring … His [Haring’s] work is faux graphic and looks ready-made, like international road signs. This immediacy is his trump card.”

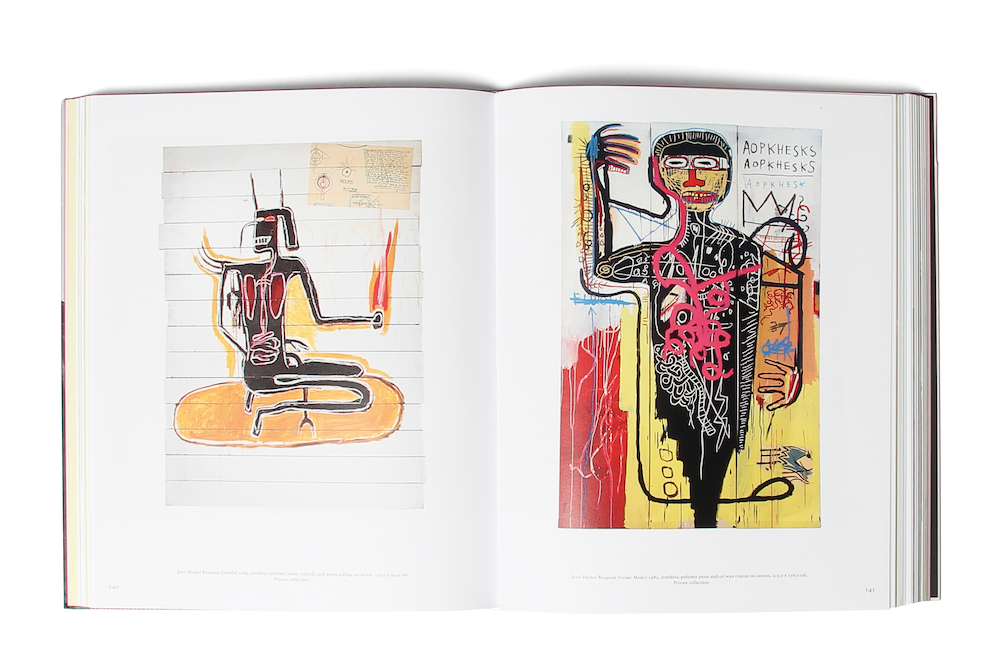

As different as the origin and education of the two artists from middle-class families might have been—Haring was from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, while Basquiat was from Brooklyn—both developed their artistic repertoire out of the humus of the lively New York art scene that had been cultivated by Andy Warhol. Along with Warhol, concrete poetry and William S. Burroughs’s cut-up technique left deep traces in the work of the young artists. In the early 1980s, during the emergence of hip-hop, with its cut-up, sample-heavy aesthetic, and the burgeoning “copy-and-paste” society more broadly, Burroughs’s practice of cutting up texts and arranging the parts to form a new text struck a nerve, and he met with late popularity. As the writer said, “Life is a cut-up. As soon as you can walk down the street your consciousness is being cut by random factors. The cut-up is closer to the facts of human perception than linear narrative.” Basquiat, aware of how fashionable Burroughs had become, noted,

I was going to say Burroughs, but I thought I’d sound too young. ’Cause everybody [says] Burroughs all the time. But he’s my favorite living author, definitely. I think it’s really close to what Mark Twain writes, as far as the point of view. It’s pretty similar, I think.

Basquiat sampled from everything around him with all his five senses; he used the “source material” that always surrounded him to create his spaces of knowledge. Like Burroughs, he created new links between various contexts and ideas, opening new spaces of thought for the audience, such as Burroughs’s basic idea that life itself is a cut-up.

The influence of Burroughs on Haring’s early text and collage works seems, in comparison, quite direct, in that the artist, also influenced by Jenny Holzer’s 1978-87 series Truisms, used the technique of cut-up to rearrange headlines from newspapers like the New York Post, which he affixed to paper using adhesive tape. He applied hundreds of xeroxes of these “headline” works, which made proclamations such as “Reagan Slain By Hero Cop” or “Reagan’s Death Cops Hunt Pope” to lampposts and newsstands in the summer and autumn of 1980, and in playing with the rearranged headlines took a clear position against authority, racism, and discrimination.

Burroughs himself paid his respects to the young artists. He met Haring personally in 1983, expressing his deep admiration for his work and comprehensive subway drawing project:

I think Keith is a prophet in his life, his person, and his work. In that way, he’s like Paul Klee, who was probably the most influential artist of the 20th century—certainly through his art, his writings, his teaching. Keith will influence other painters—probably profoundly. By association, Keith is part of the whole New York subway system. Just as no one can look at a sunflower without thinking of Van Gogh, so no one can be in the New York subway system without thinking of Keith Haring. And that’s the truth.

The two artists collaborated in 1988 on the print portfolio Apocalypse, 1988, and again in 1989 on The Valley. “Our work was of equal weight and purpose … My texts were perfectly understood and perfectly rendered,” Burroughs recalled later.

Photographic documentation shows that Burroughs also met Basquiat, who paid dubious homage to him in 1983 in his triptych Five Fish Species. Here he referred, with the words ‘BURROUGH’S BULLET©’ and ‘1951,’ to September 6, 1951, when Burroughs shot his wife, Joan Vollmer, dead in Mexico City, trying to replay the scene with the apple from Friedrich Schiller’s drama William Tell while under the influence of drugs. This radical and brutal dedication to Burroughs focuses, just like Burroughs’s own merciless depiction of life’s abysses, on the moment of his wife’s death. Basquiat thus ruthlessly evokes Burroughs’s eventful life, his rejection of social norms and his radical artistic innovations, such as the idea of life as a permanent cut-up, in an artistic fulmination against racism, police violence, oppression, and social injustice.

___________________________________

Excerpted with permission from Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines by Dieter Buchhart. Published by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved.

Dieter Buchhart

Dieter Buchhart is an art theorist and curator of numerous international exhibitions, including solo exhibitions of the work of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.