When Journalists Turn to Fiction: A Reading List

Katie Hafner Recommends Anna Quindlen, Geraldine Brooks, and More

In my four decades as a journalist, if you don’t count facts I’ve gotten wrong and scrambled to correct, I haven’t written a lick of fiction. After all, fabrication is a cardinal sin. Nor did I feel much of a pull, as many reporters do, to write a novel. Then, a few years ago, after hearing the most threadbare of true stories, I wrote one.

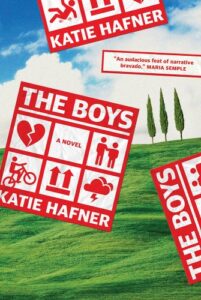

Now that the book is out in the world, people ask me what it’s like to switch from nonfiction to fiction, a question that got me thinking about journalists over the years who have made the transition. It doesn’t always go well. Once out from under the tyranny of the facts, some reporters go a little crazy with their fiction, with over-the-top prose and implausible plot lines. I was aware of this danger while writing The Boys. To keep myself grounded, I drew on reporting I’d done over the years.

Here’s a list of books by journalists who, in my opinion, moved to fiction without going overboard.

*

E.B. White, Stuart Little

When he was in college, Elwyn Brooks White was editor in chief of his college newspaper, The Cornell Sun. In 1921, at age 22, he went to work for the United Press, before becoming a cub reporter for The Seattle Times. He was fired from the Times and moved to the other Seattle paper, The Post-Intelligencer. Eventually

He spent his life toggling between nonfiction and fiction. Unaccountably, I’ve never found myself drawn to White’s nonfiction, perhaps because I will always know him as my favorite fabricator of stories. Stuart Little is, hands down, one of my favorite books. The physical book in my house when I was a little girl has long since disappeared. My memory of it is a volume completely tattered, its pages rippled with water damage. (Could it be that I took it into the bathtub with me?) I loved the story of Stuart’s amazing adventure, of course, and how normal White made it seem for a human family to have given birth to a mouse. But I also loved what I even as a young child sensed was White’s respect for me, his reader. “No one can write decently who is distrustful of the reader’s intelligence,” he once said. And that might just be the enduring link between White’s nonfiction and his fiction.

Anna Quindlen, Miller’s Valley

When I was in journalism school in the 1980s I was a huge fan of Anna Quindlen’s journalism. In 1980, she wrote one of her most memorable lines as part of a front-page series about the deterioration of Central Park. In her lede, Quindlen described the once splendid park as a “dirty, unkempt, vandalized shadow of its former self.” I remember vowing to myself that I would work as hard as I could to make my reporter’s prose shine like hers.

Quindlen’s novels are beautifully crafted and filled with turns of phrase like the above-mentioned gem.

My favorite work of Quindlen’s is Miller’s Valley, which follows the story of Mimi Miller, a girl growing up on a family farm in the eponymous town in rural Pennsylvania. Her family has lived there for generations (hence the name of the place). Miller’s Valley is a town on the decline, not unlike the Central Park Quindlen described in her newspaper story nearly four decades earlier, and Quindlen takes us through the changes in Mimi and her family. Secrets, of course, are revealed, deftly and, well, journalistically.

Geraldine Brooks, March,

What can you say about Geraldine Brooks except this: The very fact that her gorgeous writing once, if briefly, graced the pages of The Wall Street Journal and the Sydney Morning Herald speaks volumes about the range of her gifts. Like Quindlen, Brooks the journalist is everywhere in evidence in her fiction: her eye for detail, her hewing to facts, her measured tone.

Of Brooks’ novels, the one I like most is March, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize in 2016. It’s an exemplar of “what-if” historical fiction, about the absent father of the March family in Louisa May Alcott’s classic, Little Women, Brooks follows Papa March as he leaves behind his family to join the Union’s cause in the Civil War. Brooks suggests answers to questions that have surely nagged at all readers of Little Women (e.g. haven’t you always wanted to know the reason for the family’s descent into genteel poverty?). Brooks weaves this tale of another time with sweeping flights of the imagination while remaining grounded in facts (she relied heavily on primary sources for the scenes in Concord, Mass., and during wartime) and, like her journalism, the prose of her fiction is always accessible.

John Hersey, A Single Pebble

Journalist John Hersey changed the world in 1946 when The New Yorker published his 31,000-word account of the aftermath of the bomb the U.S. dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The magazine devoted an entire issue to the story.

But fiction was always Hersey’s first love. In fact, he published his first novel, A Bell for Adano, before the Hiroshima story. The book, about a fictional Italian village during World War II whose church bell was taken by the fascists to melt down for weapons, won a Pulitzer Prize. But I’m partial to Hersey’s masterful short novel, A Single Pebble, about a young American engineer sent to China to inspect the Yangtze River for potential dam sites. Pulled on a junk, the engineer journeys not just deep into China but also into the ancient ways of the people of the Yangtze. There’s something about Hersey’s matter-of-fact prose in A Single Pebble, as well as his portrayal of his fictional characters, that is hauntingly reminiscent of “Hiroshima.”

Robert Harris, Fatherland

Recently I was describing to a friend one of my favorite nonfiction books of all time: Selling Hitler, by Robert Harris. It’s the story of the fiasco surrounding the faked private diaries of Adolf Hitler. I loved that book so much I went and bought a first edition. I don’t even know where to begin with how much I admire Harris for his reporting, his powers of description, and his talent for making words march across a page. I still conjure scenes from that book. And it makes me think that when someone hones the craft of writing long-form nonfiction narratives as expertly as Harris has done, the switch to fiction might not be such a leap (Jon Krakauer, are you listening?) Harris proved this with his 1992 novel, Fatherland, a book I read on the heels of Selling Hitler and found so compelling even with its horrifying premise that I often still think about that one, too. Fatherland is an alternative history set in a world in which Germany won World War II. It’s an absorbing detective novel about a murder investigation. The whodunnit part of the story didn’t stick with me as much as Harris’s painstaking descriptions of a dystopia that doesn’t exist—but easily could.

Edna Buchanan, Contents Under Pressure

For years, Edna Buchanan was the doyenne of crime reporting in Miami (and wrote arguably the most famous newspaper lede in the English language). She reigned over crime reporting at the Miami Herald for decades, and her transition to fiction in the early 1990s felt seamless.

Write what you know, goes the adage, and she did. Her fiction career started with the first in the Britt Montero series (there are ten altogether), Contents Under Pressure. Cuban American Britt Montero is a crime reporter for a major Miami newspaper and keeps a police scanner nearby at all times. She digs for the truth after the death of a former pro football player. Buchanan’s authentic voice and unparalleled experience in crime reporting rings true throughout the entire series.

Carl Hiaasen, Basket Case

Carl Hiaasen, also of The Miami Herald, offers up a rollicking good time no matter what he writes. He started at the Herald as a city-desk reporter and went on to work for the paper’s investigations team. He was a regular columnist until 2021.

Hiaasen began writing novels in the 1980s and he broke out with Tourist Season, published in 1986.

I have a particular soft spot for “Downhill Lie,” Hiaasen’s memoir about taking up golf after a long hiatus. Of Hiaasen’s fiction, my personal favorite is Basket Case, about a has-been investigative reporter, Jack Tagger, exiled to the obit desk of a South Florida newspaper. Tagger is determined to resurrect his career by uncovering the cause of death of one of his obit subjects: rock star Jimmy Stoma, who died in a scuba “accident.” The characters—a soulless publisher and a driven young editor—might seem cartoonish, but the newspaper world is filled with people just like them.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

And what list of journalists-turned-novelists would be complete without Charles Dickens? Dickens was in his early twenties when he started writing for The Mirror of Parliament. He worked as a political journalist and traveled across Britain to cover election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle. As a novelist, Dickens’s portrayal of Victorian England, living conditions among the poor, and inhumane workplaces don’t miss a beat. It’s hard to say whether his start in journalism helped, but the question seems almost beside the point. Perhaps a more helpful jump start to his literary career was the journalistic practice of periodic publishing. The Pickwick Papers was first published in monthly installments, as were Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, and others.

My favorite Dickens by far is Great Expectations, with its detached, almost clinical examinations of both wealth and poverty. At the same time, Miss Havisham, the wealthy spinster who lives in the wedding dress she was wearing when jilted at the altar, is a product of an imagination with intention of being tethered by the facts on the ground.

__________________________________

The Boys by Katie Hafner is available from Spiegel & Grau.

Katie Hafner

Katie Hafner is a journalist and author who writes for The New York Times and The Washington Post. She is the author of six non-fiction books, including the memoir, Mother Daughter Me; A Romance on Three Legs: Glenn Gould's Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Piano; Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet (with Matthew Lyon). She is host and co-executive producer of the popular podcast, Lost Women of Science. The Boys is her first novel. She lives in San Francisco.