When it Comes to Coronavirus, What Does ‘After’ Mean?

Eva Holland on Writing About Fear

Our dystopian novels tend to finish one way or another: with the horror in retreat or with the grim realization that it is here to stay. The boys in Lord of the Flies are finally discovered on the island; Winston gives in to the terrible power of 1984’s Big Brother. Hope, or hopelessness. The End.

What we see less often, in the stories with hopeful endings, is the messy aftermath of victory. What happens to Ralph after he gets home—or, for that matter, to Jack? Sometimes I try to picture it: Ralph in therapy maybe, working through his anger. Jack punching in every day at a staid office job, in his free time quietly trying to drink the guilty memories away.

That was one thing I appreciated about Mockingjay, the last book in the Hunger Games trilogy: the glimpses it offered of the “after.” The movie version made things cleaner, more pastoral, skipping to the sun-drenched epilogue, but the book dwells a few moments longer on the ugliness in the soon-after. “Peeta and I grow back together,” Katniss Everdeen narrates. “There are still moments when he clutches the back of a chair and hangs on until the flashbacks are over. I wake screaming from nightmares of mutts and lost children.”

This period will leave its marks on us—but what will those marks look like?That felt less jarring to me than the movie’s jump ahead to domestic bliss. “Real or not real?” Peeta repeatedly asks Katniss, seeking reassurance about the world around him when he can no longer be sure of his own mind. The messy aftermath? That’s real.

*

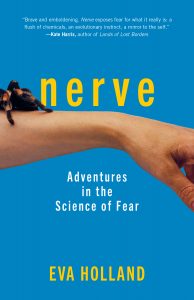

I’ve been thinking a lot about “after” lately. My first book, Nerve, was published in mid-April. It’s about fear—it pairs a personal narrative about my efforts to overcome my fears with reporting, immersion-style and otherwise, into the science of being afraid. Threads about grief, anxiety, and trauma run through it, but it’s also about memory. More and more now, though this theme never appears in the jacket copy, I think of it as a book about how our memories can shape our visions of the future—how our “before” can build our “after.”

My mother’s loss of her mother, when she was a child, shaped her adult life; my memories of growing up with a mother still devastated by that loss shaped my fear of losing her in turn. Later, as I wrestled with a powerful fear of heights, my past panic attacks informed my next ones, my brain falling into the accustomed pattern of frozen terror. And then there was the series of car wrecks I survived, the memories of which would reach out and grab me when I drove, prompting flashbacks, tears and panic, visions of my seemingly certain doom. If anxiety is a fear of the future—or an endless series of potential futures, all of them disastrous, pinging through your mind whether you like it or not—then trauma, it seems to me, is fear of the future driven by pain from your past.

All of which has led me to wonder about the aftermath of the pandemic. What comes next for us—after sickness, after lockdown, after the pandemic recedes? This period will leave its marks on us—but what will those marks look like? I think a lot of us are beginning to ask those questions, even as the “after” remains distant.

I try to picture it in the same ways I try to place Jack and Ralph in an imagined future. Many of us, I suppose, will remain relatively unchanged. A lifetime of habit will re-assert itself after a couple of years of strangeness, and we’ll revert to hugging, touching, eating with our hands from shared surfaces. Others will find that the virus, and the restrictions we endure in an attempt to contain it, linger in our minds. We’ll have anxiety about germs and hand-washing, maybe. Some of us might continue to carry disinfecting wipes, to run them over airplane seats and tray tables, the keypads of credit-card machines, the steering wheels of our cars. Some of us might focus our anxiety on our food supply, stocking our cupboards with rice and beans, yeast and toilet paper, or the particular items that we found ourselves short of.

Others among us, hopefully only a small minority, will experience the classic symptoms of trauma and PTSD: flashbacks, hyper-vigilance, acute panic and fear and anger. These people might go along with their lives, seemingly fine for weeks or years at a time, before being triggered to react. We might expect them to be clustered mostly among the first responders, the doctors and nurses and others who staff the emergency rooms and the ICUs, the overstretched paramedics in their screaming ambulances. But the threshold for post-traumatic stress is that you experience a terrifying event, one in which serious harm either occurs or threatens to occur. All of us meet that threshold right now.

*

So what will our “after” look like? It’s tempting to picture an eruption of joy, people taking to the streets, hugging and kissing strangers like they did when the Second World War wound down. My great uncle was on the first ship that sailed into Oslo after Norway was liberated from the Nazis. He once described to me the young girls that greeted the troops wearing ribbons that matched the colors of the Norwegian flag in their hair, on their dresses, after years of such displays being banned. He told me about people coming out in any watercraft they could find, a civilian flotilla to meet the Allied ships as they arrived, and the case of fancy French champagne that the sailors later liberated from Nazi headquarters.

If there’s one thing I’m hopeful about, it’s that we can be more honest, less silent, about the messy aftermath than we have been in the past.I loved those victory stories. I never asked him about anything messier, and the only hint I ever got about the messiness of his memories was the time he walked into the room while I was watching Saving Private Ryan on TV. Spielberg’s famous recreation of the storming of the beaches in Normandy was playing on the screen, and my uncle turned, seemingly angry, and walked right out of the room again.

I know my visions of our “after” can seem grim—that a victory parade through unrestricted streets is more appealing than the idea of whole swathes of society left deeply harmed, even though they survived. But if there’s one thing I’m hopeful about, it’s that we can be more honest, less silent, about the messy aftermath than we have been in the past.

Real or not real? Anxiety is real. Trauma is real. There is no fast-forward to the sun-drenched epilogue. But anxiety and trauma are also, increasingly, treatable. We are getting better at talking about them, better at easing their effects. In my most optimistic vision of our “after,” we are humane and helpful to those who are suffering. We talk openly about the damage done, and, just as we worked together when the virus was active, to mitigate its spread, we work together to heal from its scars. Our memories may help to shape our future, but they don’t have to control it.

__________________________________

Nerve by Eva Holland is available now via The Experiment.