These mountains are sublime. Primordial. Otherworldly. Legendary. Epic.

Pyrene was the daughter of Túbal, King of Iberia. And Gerió was a giant, with three men’s bodies joined at the waist, who took the throne from Túbal. Pyrene escaped into these mountains and Gerió set them all aflame in order to flush her out. He burned her alive, and Hercules covered her corpse with magnificent stones, creating a mountain range as a mortuary sculpture, from the Cantabrians to Cap de Creus. These mountains are called the Pyrenees in honor of Pyrene. That’s how dear old Verdaguer tells it. The Greeks were wilder, crazier. Greek mythology has it that Pyrene was King Bebryx’s daughter and was raped by Hercules on a court visit, after which she gave birth to a serpent. Then the princess fled into the mountains and was devoured by wild beasts. According to the Greeks, it was Hercules himself—after raping her and knocking her up with a snake—who discovered her body ripped apart by wild animals up in the mountains, and he named the mountains after her in tribute. Gee, thanks, Hercules!

This is the route of the retreat into exile. Where the Republicans fled. Civilians and soldiers. Toward France. It’s a damp morning. I inhale, bringing all that clean, wet, pure mountain air deep into my lungs. That aroma of earth and tree and morning. It’s no surprise the people up here are better, more authentic, more human, breathing this air every day. And drinking the water from this river. And looking out every day at the majesty of these legendary mountains, so beautiful it pains the soul.

I head up, toward the town. I left my car all the way down in the valley, at almost eight in the morning. I ate a stale sandwich and I haven’t even had coffee. The last time I came up here, last spring, a local told me these peaks are cursed and that every ten years somebody gets struck by lightning. He said his name was Rei, the King, with his dime-a-dozen face, toothless mouth, and skin so dry you could hear it chafing when he rubbed his nose. “Watch out you’re not the next victim,” he told me. “Run through by lightning.” And he laughed. Crested storm clouds gathered. “Watch out you’re not the next victim.” King of the nutjobs.

Emotions are more naked up here too. More raw. More authentic. Life and death, life and death and instinct and violence are present in every single moment up here. The rest of us, we’ve forgotten how sublime life is. In the city we go through the motions with our watered-down lives. But here, here you really live each and every day. As soon as the weather turns, even if it’s just a gawky bit of early spring, I have this need to get up into the mountains, at least once a month. Leave it all behind and just spend a day in the fresh air. Sometimes with a friend, sometimes on my own. If I can ever buy a little house up here, an old farmhouse, a summer place, I’ll call it Can Gentil. But it would have to be a farmhouse, because I can’t see myself in a villa.

Up here even time has a different feel. It’s like the hours don’t have the same weight. Like the days aren’t the same length, don’t have the same color, or the same flavor. Time here is made of different stuff, and it has a different value.

An early yellow sun slips through the leaves of the trees. And I hear the river flowing happily. Once I step off the damp, sunken footpath and head up, I see a few scattered homes in the distance, on the other side of the crest. The mountains there in the background, they could even be France already, with Espinavell at the far end, and, my god, what a landscape. We have such amazing vistas and incredible mountains, we should be so proud, but sometimes, crowded together in Barcelona, we forget all about them. And they’re gorgeous as anything. Eye-piercingly gorgeous. You have to come up here in the fall, when the crest line turns from one color to another, now red, now chestnut brown, now the beige of a Pyrenean cow’s snout, now ochre, now orange, now deep garnet and colors you’ve never seen before in your life, with a sun yellow as an egg yolk. Man, I love walking through these mountains. I just love it so much. It’s thrilling. The cows, the crests. And there in the distance, the Canigou. That place. Oh, how it fills the heart.

I reach the town, and the town is lovely as a postcard. With that solid, square, stately Romanesque church. The sun is already warming my shoulders, and I head farther up. The church is to my right, the first houses to my left. There are two horses, one brown and one white, fenced in, right there at the entrance to the town, just as it must have been a thousand years ago. I grab a fistful of grass and bring it up to the fence to see if I can tempt them, but they pay me no mind. Lovely. Sturdy. With valiant legs and necks like bulls. Horses of the Pyrenees, noble stock.

The butcher’s shop where I buy sausage, real sausage, the good stuff, not like what they sell in Barcelona, is just a few steps from the church. When I go up into the mountains, I always stock up. The butcher’s shop is so authentic. Truly frozen in time. With its old marble counters pink with all the blood. The wall tiles yellowed. And those crocheted white half curtains. The hand-lettered signs. And a fluorescent light that occasionally flickers. With big bottles of water lined up on the ground, and the shelves filled with everything you could imagine and more, all mixed together, and dusty and lined with red-and-white-checked oilcloth. Frozen in time. Behind the counter are an old man and a young girl, both with accents so strong you have to concentrate or you won’t understand a thing.

But the butcher’s shop is closed. I check the time. Eleven o’clock. Small towns are incredible, so chill, so relaxed in their approach to work and life. I love it. I wish everywhere was like that. I go to the bakery. Two houses down the road. Everything within spitting distance. The sunless streets are damp. The flagstones gleam dark. The bakery’s closed too. I check my watch again. Five minutes after eleven. What’s the deal here. I turn and catch up with two women. Both dressed in black. Old, old women like something out of a fairy tale. White, sparse, frizzy hair. Wrinkled faces with blotches and warts, and watery lilac lips.

“Why’s everything closed today?” I ask them.

One of them turns and regards me with disdain. She looks me up and down. She holds my gaze and replies, “We are in mourning.”

“The butcher and the baker are in mourning too?”

The woman turns her head and doesn’t answer me. Her companion, who’s somewhat less of a witch, says, “Hilari from Matavaques is dead. He was killed by the Giants’ son, in the forest. They were hunting and they had an accident and Hilari is dead,” she says. “Hilari of Matavaques is dead. Like his father. Only twenty years old. So tragic.”

I’m completely in the dark here. “A hunting accident?”

They start walking off and respond without turning. “Yes.”

They leave me standing in front of the bakery. There’s no note on the door. No obituary. Nothing. It’s a quarter after eleven. The butcher’s shop and the bakery are the only two stores in town. You can buy most anything at the butcher’s, milk and juice and even pasta and rice and wine. In the bakery there’s even more, it even has dish soap and scrubbers and mops.

I walk toward the bar. I figure I’ll have a coffee and a croissant to stave off my hunger and bad luck. Damn, I think, the bar must be closed too. I’m shit out of luck. The bar is closed. Damn! They’ve got good food. Terrible coffee. That’s one thing the mountains don’t have, good coffee. The owners live upstairs. I ring the bell. No answer. Maybe they’re at church too. I ring the bell again. The shrill sound echoes. The door to the house, right beside the bar’s gates, is of red wood with frosted panes painted with stencils and pictures of vases and plants. I hear the sound of doors opening. And through the opaque white glass, I can make out a figure descending the stairs. Fantastic, I think. A very old man opens the door. Wearing espadrilles. Short white beard, droopy cheeks, a big, honking nose, and a glass eye. An ugly opaque yellow glass eye that’s so poorly made it looks like plastic.

He says, “What do you want?”

I look at his glass eye. “Good morning.”

He doesn’t answer.

I think maybe I should have addressed his real eye. I switch. That one is like a fish eye, wet.

“Will you be opening up today at any point? I came here for a hike and I see everything’s closed.”

I look into his fake eye again. It protrudes more than the other one and looks like some sort of a gag. He doesn’t respond.

“I was hoping for some lunch, or a coffee.”

Silence.

“I thought that maybe, if you aren’t going to open up today, you might sell me a baguette? Anything, just so I can make it back to my car, it’s a good two hours away, down in the valley.”

I address his good eye in an attempt to garner sympathy.

“No.”

“Anything.”

“No,” he says, louder. “I need the bread for tomorrow!”

“But, sir, a baguette, it’ll be stale tomorrow.”

“No,” he repeats. “Go away.”

“Go away!” he says. And he shuts the door. He shuts the door! Right in my face. Now I’m about to get mad. Whatever happened to human kindness? Solidarity? Generosity? For the love of god. It’s insane. So small-minded. I retrace my steps. He would’ve sold the baguette to any of the locals, he would have given it away. He treated me like a stranger, an outsider. Just like those old women did. I head back. I pass the closed butcher’s shop on my way. Not even a note. Not even an obit. I’ve had it. I see a group of people at the end of the street, in front of the church. A lot of people. The townspeople, all in black. When I walk past, they’re bringing out the coffin. The light is deep yellow. And the whole scene, the church, the old people, the dark coffin, the wreath of flowers, the two horses on the slope, the mountain backdrop, now it looks more like a postcard than ever. Lovely. If I were a painter, I would come up here and paint these kinds of paintings. Rural scenes. The old men and women, the berets, the scarves. The sunlight falling on the church, on the wooden box. The bell tower. It’s so pretty I can’t stay angry. It’s so scenic. But, believe me, I’m still hungry, and I sure as hell don’t like that old one-eyed guy’s attitude, but beauty wins out. Life and death. I imagine that the hunter who was killed had long hair, like the knight Gentil. The townspeople pass me by, the coffin leading the way. Life up here is really tragic. And I stand there for a while, transfixed, just watching the scene unfold.

__________________________________

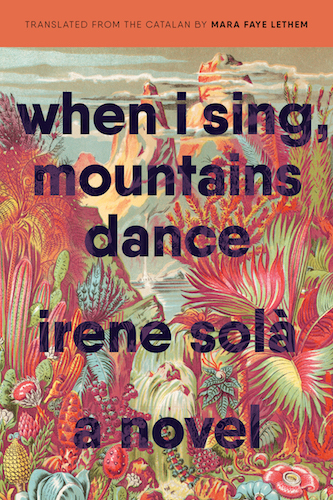

Excerpt from When I Sing, Mountains Dance. Copyright © 2019 by Irene Solà. English translation copyright © 2022 by Mara Faye Lethem. Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota.