When I Could No Longer Dance, I Found Comfort in Books

Ellen O'Connell Whittet on Living (and Reading) with Chronic Pain

Telling the story of my chronic back pain provides signposts and milestones. I can track my growth from one brace to the next. The first brace in Boston felt like restraint. The second brace, after my fall on that California winter night, felt like a bolster. Nothing had changed between those two injuries except me.

In Boston, I had known nothing of myself besides that I was a dancer. By the second time, I knew I was other things as well. I was a few years older by then, and these parallel milestones proved to me that in the intervening years, I began to let some of the rest of the world bleed into mine: the books and cities I loved, the people who saw me as something other than a useful body.

After my showstopper fall in rehearsal when I was 19, my knees pulled to my chest, staring at the fluorescent lights as the music kept playing, I knew deep down this pain was so bad I would never be rid of it. But my mind was scrubbed of anything besides panic. I didn’t want to move, but I wanted desperately to go to the emergency room to verify what I was feeling, to make sure I was really splintered beyond repair.

That night, I couldn’t get to the hospital without help so someone—I’ve forgotten who—wheeled me in. That was the only thing that seemed at all extraordinary: I sat down in a chair, the chair moved, and suddenly I was in a new place.

Three X-rays were backlit on the wall, and the doctor pointed to them as though I might recognize something in them. Mostly I saw the tree branches of my ribs, white and blurred, like an anatomical equation that I was trying to solve.

“Here’s the fracture in the lower spine. L4 and L5 have compressed here and here as well, see this bulge, and the fluid has begun to leak.” The doctor used a pen to point, but to me it looked just like it was supposed to.

“Down here is narrowed disc.” He traced them in a smooth arc. “This is mostly like the result of years of wear and tear on your spine. “If you were a normal weight,” the doctor added, “You might have had more cushion in your butt. Try to gain a few pounds, okay?”

He was looking at the valleys between my bones, my frail frame and the way my hip bones stuck out because I hadn’t eaten a full meal in months. He was looking at the soft downy fuzz that grows on a starving body to keep it warm. But who knows what would have happened if I had more weight on me. If I hadn’t danced through the pain so many times before. If every other circumstance were not what it was.

A rheumatologist gave me my diagnosis: the disc between my L6 and L7 lumbar spine was dangerously herniated, and I had torn the ligaments that held my sacrum and ilium bones together, so I could no longer keep my own alignment. He referred me to physical therapy, but I had gone to physical therapy for back pain before, and knew the limits of their understanding of the demands ballet puts on a body. Even the chiropractor I’d seen with my grandmother could only provide me with temporary relief.

I became what I was: a body in recline. A body, broken. I grew depressed, and then determined, and then depressed.

I’d overestimated my own ability to dance through pain and ended up in almost daily spasms, which the doctor assured me was my body’s way of seizing the mus- cles around the site of injury to prevent further damage. “This is a pain you should listen to,” he told me. “You really shouldn’t do much of anything as your back relaxes and begins to heal.”

“Could I just do barre?” I asked him. Surely barre was safe: only the warmup section and short combinations to prepare for dancing unassisted.

“You shouldn’t even walk much while this heals,” he replied, writing down my referral for physical therapy. “I want you to lie on a hard surface with lots of pillows under your knees for as long as it takes for the spasms to stop.” Before I left, he produced what looked like a big white Ace bandage and pulled up my shirt to show me how to strap myself in.

“This back brace will hold your sacroiliac joint in place until you can relearn to do it yourself,” he explained. As he talked, he wrapped the big white bandage around my middle and, using a little metal clip, tugged it in place to hold me together. It was tight and pinched in some places, but wearing it helped me move carefully.

In the car ride back home, I told my parents that while I was injured, maybe I’d try to write, my second favorite thing to do. “Writing hurts in better places,” I told them. In my first year of college, worried I was disappearing in my ballet classes, I’d taken a poetry class. I’d loved it—something I was able to wedge in between dance classes that fed me, even as I danced on an empty stomach. The A I earned on my poems made me feel like I had another voice. And that voice would end up saving me.

When we got home to my parents’ house from the doctor’s office, I lay on the Southwestern rug next to their age-swollen grand piano, and the sunlight dripped through the window beside me as though spilled from a pitcher. Adapting to daily pain is a full-time job that, like any other, becomes as unconscious as a gesture, hair tucked behind an ear, the absent-minded twirl of an earring. Down on the floor, I relearned each movement to minimize the pain until living that way became automated.

From the floor I lost my confidence, my sureness in what my body could accomplish. I became what I was: a body in recline. A body, broken. I grew depressed, and then determined, and then depressed. I told myself I’d just have to sit out for a few weeks until I could dance again, that I was still young enough that my body would bounce back and I’d be able to resume my life without too big of a setback.

I had my parents or my brother help me downstairs where the TV was, where I’d watch old tapes of myself dancing—as the dew-drop fairy in The Nutcracker or as Cupid in Don Quixote or a sylph in Les Sylphides. I watched the great story ballets. I watched the documentary about the young Swedish ballerina who, while doing ronds de jambes at the barre tells the man filming her, it always hurts somewhere, and just now I feel it in my hip. I watched the man’s solo from American Ballet Theater’s La Bayadère over and over, marveling at how Ángel Corella, my great love back then, could jump in the air, spin 180 degrees, and fling his legs into a split jump all within a second.

I ran through the choreography in my head from the role I’d been dancing when I fell, and imagined somewhere another girl happily stepping in, glad to be given the opportunity. It was painful to think of my friends still dancing when I couldn’t, like a betrayal. I missed the casting for the spring Balanchine ballet, so I listened to the score over and over, wondering when my body would belong to me again, wondering which part I would have gotten and which girl had it instead.

I saw while I read that the roles available to women were far more numerous and distinguished than I’d ever realized.

Days before my fall, my roommate back at college, also a dance major, had left her diary open on her desk, a purple pen uncapped in its seam. Without touching it, my boyfriend had leaned over and read, aloud, “She always complains about her back after class. I am so sick of it.” I felt the stinging heartfire of criticism, of another person witnessing my pain witheringly, and wanted to call her now and say, “See? It broke! It really did hurt!”

My pain felt like walking through a new landscape, senses at attention in a new terrain, everything crowding out everything else’s importance. Like visiting a new place, pain made me focus on a small incident to distract me from the more terrifying abstract questions: what would I do if I never healed? Why would I want to dance again if it caused me this much pain?

•

The story of the fall in that ballet rehearsal when I was 19 is the showstopper, but it’s not what stopped me from dancing. The years that followed did. Chronic pain is anticlimactic both to the sufferer and an audience: a new landscape no one would choose to visit. No one asks to see your back brace like they do pictures of where you’ve traveled. No one asks you questions about whether they should go to this new place too, where they should sleep or visit. Instead, chronic pain is isolating—both as I lived it and as I remember it years later. I feel it to this day, especially when I sit for long periods while I read or write.

That kind of recovery left me more time than usual to read, something that I usually did only between class and rehearsal. Now, I could devote the time between injury and recovery to it. I began reading through a book list of great women writers. While my friends back at college were learning new choreography, getting sunburned together on the weekends, I read Rebecca and Lolita, Mrs. Dalloway and My Antonia.

They were the only thing that allowed me an interior life compelling enough to forget about how my body felt. They gave me a softer landing so I did not splinter when I met the ground. They acted as a much stronger brace than the one I wore around my back. The books I read those months that I healed are still among the most important of my life.

I saw while I read that the roles available to women were far more numerous and distinguished than I’d ever realized, that lives could be exciting without ballet as an escape hatch. Some women didn’t need an escape hatch at all. I saw women who cast themselves in the parts they wanted—traveler, public intellectual, part of a community of artists that debated their work, wrote on their own terms, took risks, broke rules. I looked for myself in the pages of each novel I read. I saw women focusing on something other than the size of their bodies. Women in novels like Madame Bovary and The Awakening would rather not live at all than live in a small, stifled world.

__________________________________

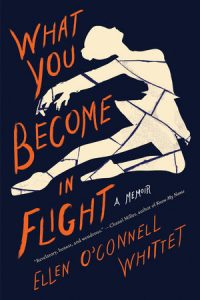

From What You Become in Flight. Used with the permission of the publisher, Melville House. Copyright © 2020 by Ellen O’Connell Whittet.

Ellen O'Connell Whittet

Ellen O’Connell Whittet is the author of What You Become in Flight (Melville House 2020), a memoir of ballet and injury. Her writing has appeared in Buzzfeed, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Vulture, and elsewhere. She teaches writing at UC Santa Barbara. You can find her on Twitter at @oconnellwhittet.