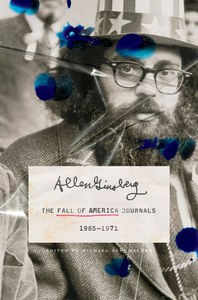

When Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder Roamed the Pacific Northwest

The Trip, in Ginsberg's Own Words

Allen Ginsberg spent the first half of 1965 out of the United States, visiting Cuba, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Poland, and England. His travels were both exhilarating and disappointing. In Cuba, where he was to attend a poetry conference and judge a poetry contest, his rebellious, outspoken demeanor ran him afoul of Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government, and he was expelled from the country and shipped off to Czechoslovakia. The early portion of his stay was pleasant enough, highlighted by meetings with students and readings in coffeehouses that treasured the writings of the Beat Generation.

With his earnings from readings and book sales, Ginsberg was able to afford a visit to the Soviet Union, the land of his ancestry, and Poland, another country he had hoped to include in his busy schedule. The notebooks and journals he had kept throughout these travels, published in Iron Curtain Journals: January–May 1965, contained new poetry, travel prose, dream entries, and fragments of conversation with such literary luminaries as Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky and comprised some of Ginsberg’s most arresting writings to date.

His return to Czechoslovakia was less successful. Treated as a hero by the young people of Prague, he was elected “Kral Majales” (King of May) during the country’s May Day festival—a status that did not sit well with the country’s authorities. He was subsequently stripped of his crown, and in the days following the festival, Ginsberg was followed by government operatives, attacked and beaten on the streets, and had his journal stolen; he was arrested and interrogated about his comings and goings, and, much like in Cuba, he was tossed out of the country, supposedly for being a bad influence on Czechoslovakia’s young people.

Fortunately for Ginsberg, the Czech officials sent him to London, then flourishing culturally during the “Swinging England” period. He hung out with Bob Dylan and the Beatles, and he helped organize and participated in the literary touchstone international poetry reading at the Royal Albert Hall, an uneven gathering of poets who proved, if anything, that there was great potential in a huge poetry reading. England offered Ginsberg an ideal environment in which to decompress after his experiences in Cuba and Czechoslovakia.

Ginsberg’s adventures overseas prepared him for what lay ahead when he returned to the States at the end of June 1965. The Vietnam War and the civil rights movement dominated the news. The Voting Rights Act, the jewel of Lyndon Johnson’s proposed civil rights legislation, passed after contentious debate and virtually no Republican support, and went into effect on August 6, 1965. By banning state and local governments from finding ways to skirt the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution, the new law guaranteed the vote for black and other minority voters. The fighting in Vietnam, steady since Johnson became president following John F. Kennedy’s assassination, escalated after the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam attacked an American military installation near Pleiku in February 1965. Ginsberg, already an opponent of the war, became fixated on the events in Vietnam, and he used the war as a backdrop to his writings.

Ginsberg began planning an ambitious project, a book of thematically connected poems, a collection that “discovered” America in poetry similar to the way Kerouac’s On the Road had explored the country in prose. The Vietnam War would be a constant presence overhanging Ginsberg’s travel writings like a darkening shadow affecting daily life in the country. It would be a study of contrasts: natural beauty slammed up against an ugliness that rose out of the tensions of violence.

Two turns of events made the project possible. First, Ginsberg won a Guggenheim fellowship that awarded him enough money to afford a Volkswagen camper, which he equipped with a bed and a small desk and refrigerator. Second, Bob Dylan gave him enough money to purchase an Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder, which Ginsberg would use to dictate his observations and thoughts instantly, unencumbered by the process of writing everything in a notebook. Ginsberg modified the Uher, cutting the tape speed so he could fit more on a tape.

His project began on the West Coast, where he was scheduled to participate in a poetry conference in Berkeley in July. He was reunited with Gary Snyder, and the two men decided to explore the Pacific Northwest together when the conference ended. Snyder, a first-rate outdoorsman with a poet’s sensibilities, was an ideal travel companion.

–Michael Schumacher, editor

*

Sept. 10?—Wed.

Yesterday clear sunny day after Glacier Peak climb, white pass camp emptied of Labor Day weekend visitors—we moved into shelter instead of camping out on ridge protected with mountain hemlock and alpine fir trees—wandered slowly up White Mt. to its green peak topped with geological survey—orange flag—looked around for an hour or more, singing Hari om Nomo Shiva in high tender voice, then ran down the ridge to White Pass clomping down so heavily my ankles ached later and blisters on my heel and ball of left foot. Then we descended Salk North Valley big long rocky path along White Mountain side down past blueberry patches, looking into the river bottom & forests of hemlock & fir & pine trees—entered a deep forest of shady Lowland White Fir and Western Hemlock. To a rustic cabin with a strange outhouse, sunk & tilted into side of a Rene-needle stream hillock under the great trees—Entering the outhouse I lost my balance, House of Mystery, all the cracks and angles leading parallel in wrong direction—Giggled next morning when Gary went to take a crap and came back amazed.

Sept. 10—Wed.

Came down from White Pass in afternoon after clear azurey afternoon looking at Monte Cristo Range & Sloan Peak, lolling on the grass and heather near the shelter, all the tall small-stemmed flowers trembling in the breeze amid the dead silence and stillness of immense meadow gulf and crag.

Walked down long path the side of White Mt. to a shelter of White Cheek Creek & slept the night—a long dream of finally meeting Ezra Pound—a short Jewish fellow he was in fact, and some strange professionally spiritual conversation with him, we had some rapport based on assumption of immortality and Chotspuk.

Woke in the cabin my feet hurt from the jarring Fudo-strides downward on the blueberry patched trail into the dusty stones so bandaged a blood-blister on my foot-ball and we walked the 5 miles more thru hemlock forest almost tropic-rainy in style like Chiapas—instead of Palenque’s Elephant ears, giant leafed bushes, here were Devil’s [?] leaves—2 foot green frond-plates big as a car fender.

Drove up highway 9 to turn-off to go to State Park on Puget Sound near Indian fishing-reservation towns—cooked first downland meal in a week tinged salmon with a dressing Gary’d ordered—butter tarragon & a little vinegar—we talked about Peter, drank hot saki and argued and laughed—

Coming down into logging town in mid-cascades named Barrington, we shopped for groceries, I bought some crème colored streamlined Wrangler levis—my old Salvation Seattle pants had huge wear-holes in the seat already I left them in the trash-bin at Sloan Creek Camp and put on hiking shorts—so when we hit this first town and I walked out of the street, a group of young girls that passed me Main Street stared and noticed my long beardy head and potbelly and thin muscular legs—I must be a funny combination now, grey in my Temple of Beards—

At the small supermarket shopping for fish—the first newspaper in 8 days—India and Pakistan at war—bombings on Indian and Pakistan cities—Gary and I both winced, astonished and disgusted—What, has it come to that too?—

In sleeping bag on air mattress under tall thin trees in a fir grove by the road at Puget Sound, I slept, silence in the night but for frog croaks answering each other in the state camping park, and motor sounds from the bay and highways—

Dream—I visit a friend’s apartment in NY—old Columbia acquaintance—Joe Kraft?—They treat me fine as a rare queen? literary guest—big neurotic—Jean Genet is there, I discover, a young moonfaced pasty-kid, (a little physically like Arrabel) we’re on a couch lying side by side like in bed together, sweating a little (in my sleepbag)—I pluck him for conversation in front of my fellow jewish college graduates, he’s reluctant but I go on describing my relation with Peter—in a voice loud enough for all to hear, since the whole party is hanging on to the conversation between trips to the kitchen for cheese dips and vodka martinis—the faces change, one minute it’s my Uncle Maxie the next minute Jason Epstein the next minute a Danish journalist—How many people share this old fashioned cooperative apartment, anyway?—An old family apartment I had thought now all these new “young generation” mustached balding ambitious publishers have taken it over—Genet is resisting my charms, we’re in bed together, I try to forget I’m a bearded balding ambitious “young” poet and tell him about Peter, I give up and go down the elevator leaving the evening early, nothing is happening and Genet has gone too—As I leave the lobby of the building I see a new group of party arrivals—“Paris Review Crowd” meaning George Plimpton and girls, all holding arms in line in nice suits getting into the elevator—wait, who else is there?—Red Grooms and his wife, well, it’s one of the old families nice NY parties “[?].”

I woke in sleeping, got up to pee in the bushes in the chill evening air, heard frog croaks and motor noises, searched out my ballpoint pen and journal to write the dream.Meanwhile we are all discussing the war and my only comment to everybody in the room was, “When they saw the headlines everybody winced! Oh, no! Not that. Not even them!” Caught in this world madness of overpopulation hysteria and waves of violence and newspaper war and bombing and murderers all senseless under the evening stars on Main Street Paterson—I was walking there near the library and passed the shoemaker’s shop—earlier in the dream I’d met the orthodox bearded shoemaker’s son, his father, he explained, was still a young man, had had his children early—as I walked past the window of the shop I saw a man with beard and yarmulka seated at shoe-last before the plate glass window inside looking up at me, young faced, and I recognized him to be the father, and he recognized me too for whoever disreputable celebrity I was supposed to be in dreamlife, but I didn’t feel like addressing him thru the window so walked on, hoping the son in the back of the shop or in the open yard wouldn’t spot me—When I came to the small baseball park nearby I saw a picnic of orthodox families children—a nice park like the back yard of some old fashioned house, the lawn all green and well kept hedges behind high wire fence—The son was there with his red beard (Alexi Simonoff?) and greeted me—Everybody winced—

I woke in sleeping, got up to pee in the bushes in the chill evening air, heard frog croaks and motor noises, searched out my ballpoint pen and journal to write the dream—meanwhile running thru my mind, what did Indira Gandhi and Pupil Jayakar now think of Albert Hall reading, and what does Mr. [?], the Indian delegate to Pakistan, say, and Burroughs is right, the world will be in destruction the cool blue silence of imagelessness is settled into the valley lands, and the [?] are right, “Prepare for the Wrath to come” and the millenarian and apocalyptic sects are right, the shakers cut loose from radio and TV selling their Oregon farmlands prepared to be independent and chill their milk in cold spring-houses when the power gets cut off and the electric civilization breaks down and I am wrong to make a public image of myself and be identifiable at all instead of slipping silently into my enlightenment and calm peaceful obscurity traveling beardless in Volkswagen or hiding out on a farm because when the war hysteria hits a peak and chaos police emerge victorious I’ll get my neck cut off for bragging and screaming in public with my picture in the paper and a sign hanging around my neck, “Smoke Marijuana.”

3:30–3:45 by transistorized flashlight.

__________________________________

From The Fall of America Journals, 1965-1971 by Allen Ginsberg; edited by Michael Schumacher. Copyright 2020 by Allen Ginsberg, LLC. Published by the University of Minnesota Press.