Whatever You Do, Don’t Let Your Cat Do This

Veterinarian Dr. Amy Attas Offers Some Obvious Advice to Oblivious Pet Owners

Nine months after starting my house call practice, on a beautiful day in May, I was scheduled to visit the Fifth Avenue home of a new client for their two cats’ annual checkups. When George and I arrived, the doorman called up to the apartment to announce us. “Would you like them to take the North or South elevator?” he asked the residents. “And which floor would you like them to come to, the fifteenth, sixteenth, or seventeenth?”

As we rode in the private elevator to the selected seventeenth floor, my head was spinning. A triplex penthouse apartment, with each floor spanning the entire building and all with Central Park views? This was truly a palace in the sky. I was still new to house calls, but I already knew that there weren’t many homes like this in Manhattan.

The elevator opened into the apartment’s grand living room. When I think back on it, the room had the kooky exuberance of the Baz Luhrmann set in the movie Moulin Rouge. Colorful and chaotic, the vast space was encased in hunter green wallpaper with exotic birds and flowers. The room was filled with eye candy, a six-foot-tall sculpture of an elephant draped in an Indian sari, a huge shiny Jeff Koons teal balloon dog, and an eclectic collection of pricey furniture. There was a Danish modern chaise, a pop-art Lucite coffee table, and a massive rococo red velvet couch with gold tassels on the arms. On the couch sat two large pillows embroidered with the words “The Queen Sits Here” and on the other end “The King Sits Here.”

Being a house call vet, I see for myself the pet hazards that lurk in a client’s home.

A woman with a blond pixie cut named Betty (the Queen, I assumed) came to greet me with an outstretched, muscular arm. She was petite, very attractive, and impossibly fit.

“King, come to the living room. The vets are here,” she shouted into another room.

“Coming, Queen!”

Her husband entered, followed by two adorable cats. He introduced himself as Don. He too was very attractive and impossibly fit.

They actually called each King and Queen right in front of us without any sign of embarrassment or irony. I couldn’t make eye contact with George for fear I might start giggling.

Their two cats, Roast Beef and Noodle (not Prince and Princess?), rubbed against my pant leg. I bent down to give chin scratches and Roast Beef, a large black-and-white, flopped to his side, exposing his fat belly and purring loudly.

Then another voice called the cats’ names from the floor below, and the felines immediately ran down the stairs.

Betty laughed. “Polly is probably feeling lonely downstairs. They always come when Polly calls them.” Who is Polly? Maybe the housekeeper? Reading the question on my face, she explained, “Polly is our parrot.”

Right on cue, Polly, a large rainbow-hued bird, who looked like she came out of the wallpaper, flew into the room and perched on a curtain rod, followed by the trotting cats. Betty coaxed the parrot into its golden cage and then sat down on the couch by the Queen pillow. Don took his spot by the King pillow.

“Have a seat,” said Betty, motioning me to the Rococo chaise opposite the royal couch. “Let’s talk cat.” As I sat, my gaze was drawn to the floor-to-ceiling windows and sliding doors that opened onto the wrap-around terrace, beautifully planted with flowers and trees.

I began to explain my house call practice and how the exam would proceed. As I talked to King and Queen, I noticed Roast Beef casually walk past us and go through the open sliding glass doors and out onto the terrace. He was followed by Noodles. They immediately began running and playing outside. Before I could get my words out, Roast Beef jumped up on the parapet wall, two hundred feet above the ground, and ran along it.

“Oh my God! Your cats are on the terrace!!” I yelled, already on my feet, running toward the sliding door.

Queen Betty said, “Relax, they go out there all the time. They love to play outside so we leave the door open for them.”

“No! No, you can’t do that. It’s incredibly dangerous.”

“It’s fine. We’ve had cats all our lives. We always let them outside.”

I opened my mouth to try again but the look on her face made it clear that the discussion was over.

They might have always kept their terrace doors open and never had a problem before, but that didn’t make it safe for their cats. Every year, during the first beautiful days of spring, New Yorkers in high-rise buildings throw open their windows and balcony doors and literally hundreds of pets—mostly cats—accidentally fall to the pavement below, sustaining serious injuries or, worse, dying on impact.

Five years earlier, in 1987, while I was an intern at the Animal Medical Center, two of that hospital’s surgeons published a first-of-its-kind study in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association about what we now call High-Rise Syndrome. When the report initially came out, people were horrified, thinking that the authors were throwing cats out the windows at the hospital. Of course not! At that time, the AMC was also the only emergency hospital open twenty-four hours a day in New York City, so most of these cases went there. They compiled statistics on the 132 cats that were diagnosed over a five-month period with severe injuries sustained due to plummeting from high-rise windows, balconies, and terraces.

Among the important retrospective findings was that a cat’s survival following a high-rise fall depended on how far it fell. Cats are uniquely equipped with a natural “righting reflex” where they can twist in midair to position themselves feet down during the descent. If a cat falls from six stories or higher, it usually has enough time to right itself and reach “terminal velocity,” meaning the cat would stop accelerating. Their bodies would relax and they could land feet first. They might survive, but they likely still suffered fractures, contusions, shock, or ruptured internal organs. What’s really fascinating is that a fall from less than six stories was much more dangerous because then the cat did not have enough time to right itself and relax before impact, making its injuries more profound. Cats that fell from much higher floors—say, the seventeenth—weren’t included in the study, because, sadly, those cats typically died and so weren’t brought to a veterinary hospital for care.

As an intern at AMC, I saw at least ten cat High-Rise Syndrome cases, and most of the cats required urgent, costly treatment. Sadly, some who survived the fall had injuries so severe that the only humane thing to do was to euthanize them. These were young, healthy cats—on average, two and a half years old—who were just doing what cats do: exploring, playing, napping on a windowsill, or trying to catch a bird that flew by. All their needless pain and suffering, expensive surgeries, and early deaths could have been prevented by their owners simply closing windows and doors.

The paper was published years before my first visit to the King and Queen’s whimsical palace in the sky, but it was fresh on my mind because of Steve’s recent experience. Just a few weeks before, he was walking on 57th Street when a falling cat landed with an awful splat on the sidewalk right in front of him and died on the spot. By pure luck, no person was injured by the falling cat. Steve immediately went home to hug and kiss Mieskeit and confirm all our windows were tightly closed. It took him a long time to get over witnessing this tragedy.

I’m sorry to be so graphic, but people need to shed the belief that cats are unscathed by precipitous falls. I don’t care how many “lives” we think they have, no cat is going to plummet hundreds of feet onto concrete and do well, if they even survive.

As an in-hospital vet, I wouldn’t know if my clients had a terrace at their apartment or whether they leave their windows open. I wouldn’t even think to ask. But being a house call vet, I see for myself the pet hazards that lurk in a client’s home. It’s a huge advantage to see my patients’ home environments, scan for dangers, and advise the client how they can prevent a potential tragedy.

It’s sad enough to lose a patient to a disease that medicine can’t cure, but I refuse to lose another one to a preventable accident.

The only problem? Clients who refuse to heed my warnings.

I tried again with Queen Betty and King Don. “Listen to me, please.” I urged. “Hundreds of cats die or are seriously injured from high-rise falls every year. I have personally treated too many of them. You can so easily prevent this from happening just by keeping them off the terrace.”

“They love it, and I’m not going to stop them,” said Don, issuing a royal decree.

I’d only been a house call vet for a few months and so lived in constant fear that my practice would crash and burn at any second. I needed every client I could get, especially ones like Betty and Don who had multiple cats and lots of pet-owning neighbors. They clearly had very strong opinions about how they did things with their animals. I’d resolved “no Devil fish on my watch!” but in this instance I lacked the courage of my convictions to push back hard and possibly lose the clients.

To this day, I wish I had. I should have said, “You have a really cute cat. I like him. I want him to live to a ripe old age,” or stronger, “If you don’t close that door and keep it closed, I cannot be your veterinarian.”

Instead, the cat got my tongue, and I didn’t say another word about it. I gave Roast Beef and Noodles their exams and vaccinations and continued to see them, despite the open terrace every time I went. Roast Beef became one of my favorite patients. Whenever I worked on him, he did his charming “flop and purr” as soon as I began petting him.

Two years later, on another glorious day in the spring, Betty called me. “Dr. Amy, I have some bad news,” she said. I could hear from the timbre in her voice that she’d been crying. “Roast Beef died.”

My stomach plunged. “Oh my God. What happened?” I already knew what she was going to say.

“I couldn’t find him anywhere, and then our doorman called to say Roast Beef was dead on the sidewalk. He’d fallen off the terrace and landed on Fifth Avenue.”

“I’m so very sorry,” I said. “He was such a sweet boy. I’ll miss him.”

My God, what a waste of a life. I was angry and upset, but I held that in during the call. It’s not my nature to rub a tragedy in someone’s face. The next time I went to see Noodles, the terrace door was finally closed. This family learned its lesson the very hard way.

Thereafter and forever, one of the first things I do when I enter a client’s home is to check that the windows, balcony, and terrace doors are closed or screened or open just a crack if they must be at all. And after Roast Beef’s death, if a client refuses to take my advice about how to protect their pets from a high-rise fall, I do refuse to be their vet. I have lost clients, but with no regrets since I did not lose patients. It’s sad enough to lose a patient to a disease that medicine can’t cure, but I refuse to lose another one to a preventable accident.

__________________________________

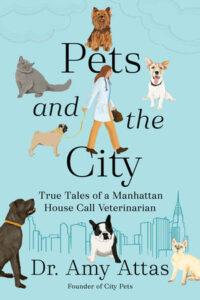

From Pets and the City: True Tales of a Manhattan House Call Veterinarian by Dr. Amy Attas. Copyright © 2024. Available from G.P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Dr. Amy Attas

Dr. Amy Attas is an award-winning veterinarian and the founder of City Pets, which for more than three decades has been the premier veterinary medical house call practice for dogs and cats living, working in, or visiting Manhattan. She shares a home with her husband, Stephen Shapiro, and if she is lucky, some rescued pugs.