"Whatever!": In Defense of Anachronism in Ancient Rome

James Hynes on Navigating the Past and the Present in Historical Fiction

Five times in my historical novel Sparrow, the character Calidus, a young provincial Roman who is the oldest son of a brothel owner uses the late twentieth century idiom, “Whatever.” On each occasion one of his free employees is telling him something he doesn’t particularly want to deal with. Twice he waves his hand dismissively, once he raises his hand to forestall an objection, and on another occasion he sighs as he says it. I’m no expert, but my recollection is that this use of “whatever” first became common in the 1980s, when it was used mainly by lippy kids in sitcoms or exasperated girls in teen comedies. When it first popped out of the mouth of a character in my novel, it stopped me in my tracks for a moment. Did I really want Calidus, an arrogant young slave owner in late fourth century Roman Spain, to come across like Molly Ringwald in The Breakfast Club?

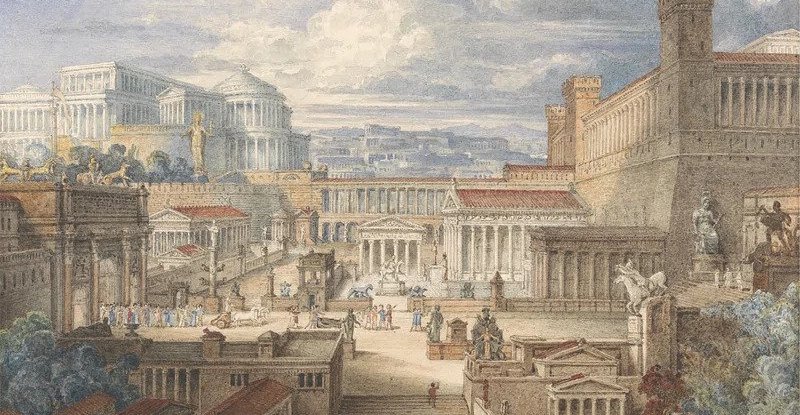

Writing dialogue for characters in historical fiction is always tricky, and the further back in time you go, the trickier it gets. If you’re writing a story set in an American or British city during the mid-twentieth century, you have reams of literature and hours of film from which you can steal idioms, catchphrases, and slang, and even if you go further back—to, say, the reign of Henry VIII—you can still do a fair approximation of how people might actually have talked. But if you’re writing a fictional narrative set in classical or late antiquity, and you’re writing it in English—the market for novels in Latin or Koine Greek having dried up somewhat in recent centuries—you have to resolve the problem of how to, on the one hand, make people sound period appropriate, and, on the other, be psychologically and emotionally understandable to a twenty-first century reader.

Both history and historical fiction will inevitably get the past wrong, because there are things that only people who lived it could know.

Walking the line between fidelity and accessibility in writing dialogue is just a minor instance of the much larger question of whether it’s even possible to evoke how characters in the distant past thought, how they saw the world, and how they saw themselves. Some critics of the whole genre of historical fiction argue that it simply can’t be done, and no one more famously than Henry James. Here’s his famous take-down of the genre, from a letter to Sarah Orne Jewett after she asked him to read her historical novel in progress: “The ‘historic’ novel is, for me, condemned, even in cases of labor as delicate as yours, to a fatal cheapness….You may multiply the little facts that can be got from pictures & documents, relics & prints, as much as you like—the real thing is almost impossible to do, & in its absence the whole effect is as nought; I mean the invention, the representation of the old consciousness, the soul, the sense, the horizon, the vision of individuals in whose minds half the things that make ours, that make the modern world were non-existent….”

And yet we persist, those of us who love to read and write historical fiction. One way I’ve thought about this problem is to consider how closely analogous the question of evoking the distant past in fiction is, to the decisions made by translators. If you’re doing the deeply alien world of the Iliad and the Odyssey, you might want to hew as closely as possible to the original’s patriarchal, honor-bound mindset. But what about when you’re translating sophisticated urban Romans like Martial or Juvenal? Juvenal’s snide takedowns of Roman life might have come from Tom Wolfe, and the Ovid who wrote about how to meet girls at the chariot races sounds a lot like the creepy pickup artists of the present. In rendering older works into modern English, some translators err on the side of accessibility rather than fidelity to the original text, privileging the feeling of the text over the letter of it. Hence we get Maria Dahvana Headley’s lively new translation of Beowulf, which translates the poem’s opening exclamation “Hwaet!” as “Bro!” Historical novelists make the same kind of calculation, balancing the weirdness and unknowability of the past with the understanding that even people who lived under a different zeitgeist are still recognizably human. Some writers even lean into anachronism: in Charles Johnson’s National Book Award-winning Middle Passage, which is set aboard a slave ship in the 1830s, the narrator, the freed slave Rutherford Calhoun, is aggressively and deliberately anachronistic—a hipster, a hustler, and a polymath who sounds like he walked right off the streets of James Baldwin’s Harlem.

Even authors who frequently and publicly profess their fidelity to the historical record allow themselves some leeway. Hilary Mantel repeatedly said that she disapproved of writers who altered the historical record, that it was the historical novelist’s duty to stick to the facts. But that didn’t stop her from telling the story of Thomas Cromwell in gloriously twenty-first century prose, and to give her characters an immediacy that belies the fact that they lived in a vastly different world. In Wolf Hall, the first meeting of Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn results in a sparring match that wouldn’t have been out of place in a movie by Billy Wilder or Preston Sturges. “Alone and bored at York Place,” Anne sends for Cromwell, and when he asks her to help restore Cardinal Wolsey to the king’s good graces, she tells him, as she diffidently plays with her dogs, “Very well. Make his case. You have five minutes.” And Cromwell says, “Otherwise, I can see you’re really busy.” Delivered extra dry by Mark Rylance in the television version, it’s a line Ryan Reynolds might have said in Deadpool. It has the contemporary snap of screwball comedy—and yet it’s utterly believable in the context of the scene, and the era.

Lest you think I’m arguing that “People in the Past: They’re Just Like Us!”, I’ll make this distinction: the form of wit is timeless, but the content of it is historically contingent. People throughout history have always made wisecracks, but what’s appropriate to make jokes about can change drastically over the centuries. The form of the Roman satirist Martial’s jokes in his epigrams is instantly recognizable to a modern reader, but some of the things he makes jokes about—having sex with slave boys, for example—aren’t just unfunny now, they’re horrific. Seeing the Roman world the way Martial saw it, where some people were playthings for his personal pleasure, may not be merely technically impossible, as Henry James wants us to believe, it may also be immoral. And that brings me to what Henry James gets wrong about historical fiction.

Both history and historical fiction will inevitably get the past wrong, because there are things that only people who lived it could know, things that not even historians can understand or explain. But then no writer, if we’re being honest, can get ever really get into the head of anybody, in any era. That’s one of the fruitful paradoxes of all fiction writing: in real life, each of us walks around locked in our own braincase, unable to truly communicate to anyone else who we really are, and equally unable to know what any other person is really thinking. But fiction, through the useful trick of using imaginary people to whom these limitations do not apply, allows us to have direct access to the consciousness of other people. As E. M. Forster famously wrote in Aspects of the Novel, “The hidden life is, by definition, hidden. The hidden life that appears in external signs is hidden no longer, has entered the realm of action. And it is the function of the novelist to reveal the hidden life at its source: to tell us more about Queen Victoria than could be known, and thus to produce a character who is not the Queen Victoria of history.”

The more I entered into this narrative, the less it became a merely technical challenge I had set myself, and became necessary.

More importantly, historical fiction can show the past in a bright, retrospective light. It can show us things about the past that the people who lived it either did not know, did not understand, or refused to acknowledge. Along with a great many modern historians, historical novelists have helped correct and expand the history of American slavery, for example, by speaking in the voices of the enslaved; Toni Morrison’s magisterial Beloved has long since surpassed Gone with the Wind as the most influential fictional narrative of American slavery. Pat Barker’s novels about the aftermath of the Trojan War, The Silence of the Girls and The Women of Troy, let the women in the story speak in their own words about enslavement, sexual exploitation, grief, and endurance. And Emma Donoghue’s Slammerkin subverts the trope of the jolly, amoral eighteenth-century whore to create a narrative that manages to be simultaneously bawdy, brutally honest, harrowing, and humane.

Early on during my research for the novel that eventually became Sparrow, I learned that—unlike the record of American slavery, which includes hundreds of first-person accounts by former slaves—the history of the Roman world includes no surviving accounts of slavery by the enslaved. There are works by people who used to be slaves—the playwright Terence and the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, for example—but there is no Frederick Douglass or Harriet Jacobs of the ancient Mediterranean world. Or if there ever were, none of the medieval monks who laboriously copied out Cicero, Caesar, and Seneca saw fit to preserve their works. Much of the reason I wrote Sparrow was to try to redress this absence, by combining research, imagination, and empathy to give one slave, at least, a chance to reveal his day-to-day struggle to endure and perhaps even find love and meaning in a brutally unjust world, and to say in his own words exactly what he thought of the Roman empire and its way of life.

And while I labored to keep obvious anachronisms of thought or feeling out of the story, and to evoke the strangeness of a world that saw identity, race, and sexual morality very differently than we do, I also wanted the book to be lively and vivid and accessible, to a show a modern reader characters she might recognize from her own life, even if she doesn’t recognize or approve of how they saw the world. The more I entered into this narrative, the less it became a merely technical challenge I had set myself, and became necessary. At the risk of sounding grand, Sparrow is intended as an act of testimony, to give voice to the voiceless, to tell history from below, to reveal the ancient world that surviving ancient writers refused to show us.

And if that’s fatally cheap or anachronistic…well, you know. Whatever.

__________________________________

Sparrow by James Hynes is available from Abrams Books.

James Hynes

James Hynes is the author of Next, The Lecturer’s Tale, and Publish and Perish. His essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, Boston Review, Mother Jones, and Salon. He attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has taught fiction writing at the University of Iowa, the University of Michigan, Miami University, Grinnell College, and the University of Texas. He lives in Austin, Texas.